Have kids' books lost the plot?

Short sentences and large illustrations are rapidly becoming the norm

Hardcore readers amongst you may have found yourself nearly fainting in shock upon goggling at the colourful illustrations colonising every page of every children's novels in bookshops today. In this rather unfortunate situation, please bring extra cushions, because if author Anthony Horowitz — who brought us the adventures of teen spy Alex Rider — is in the vicinity, he, too, may partake in this fainting expedition.

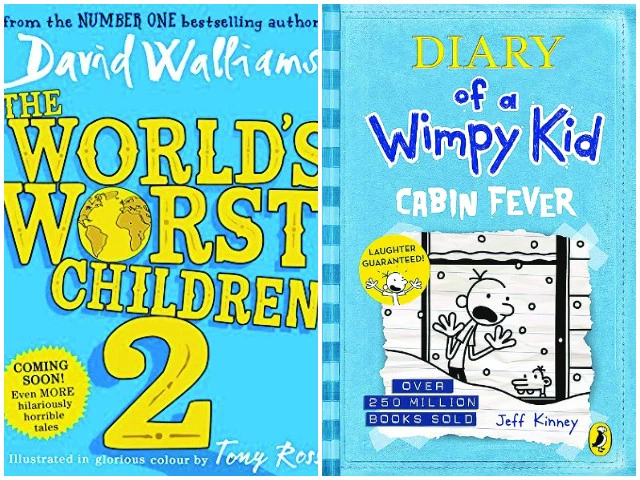

Please not that I am not pointing fingers at Julia Donaldson's picture books replete with witty quatrains about gruffalos to lasso the fleeting sanity of parents of toddlers; I am referring specifically to middle grade books (or junior fiction aimed at ages 8-12) positively bursting with cartoon illustrations, the 'pick me' of books in an era when reading is a tedious chore assigned by the greater good (as opposed to an addiction rivalling the pull of nicotine). Yes, Wimpy Kid tomes with your stick figures and literally anything trotted out by David Walliams: this means you.

What Horowitz says

"I have misgivings about the world of children's books," Horowitz comments during a recent appearance on the Headliners podcast. "You know if you look in a bookshop, the books that seem to be popular — and I'm not decrying them for a minute because they are giving children pleasure — tend to have very bright colours on the cover and [a] sort of slightly cartoonish look."

Lamenting the steadily rising number of attention spans repulsed by (or terrified of) the prospect of anything over 300 pages, Horowitz's complaints about modern children's books are not over — and nor that they are without scientific merit.

"They're very short, they're big type, they're lots of pictures... that seems to be now what is more popular and it's not what I write," he continues as he goes on to blame social media for snipping away at attention spans.

For the cynical adolescent or Gen-Zer, it is almost impossible not to dismiss Horowitz's misgivings as the rantings of an old man yelling at clouds. To them, Horowitz is merely gazing longingly into what all of those in their (our?) advanced years love more than anything else in the whole world: the rose-tinted rear view mirror.

Even as we snooty lovers of (proper) fiction nod in agreement with poor Horowitz, far too many of us will blush at the memory of our parents' visceral horror in the '90s at our deep love for the almost bottomless well of Sweet Valley Twins, Nancy Drew, and the ageless Hardy Boys (the lifeblood of Karachi bookshops in the nineties). To add salt to the wound, we callously eschewed the works of JRR Tolkein, CS Lewis, and (worst of all) Mark Twain tentatively suggested by hopeful elders. Now, thanks to the circle of life, the time has come for us to issue those horrified elders a sincere mental apology and unabashedly join Horowitz as we, too, lament over the decidedly downward spiral children's fiction is on.

Is it really rose-tinted glasses?

Heavens, no. A casual riffle through the children's section will yield colourful Quentin Blake-style illustrations beefing up the text with relentless tenacity. Short, sharp sentences and random capitalisations (in a larger font size to truly ram home the point) festoon almost literally every page lest the sight of unremitting lines of text fail to lure you in. Children's novels have assumed the hard-copy appearance of a Tumblr (or Instagram or Facebook) rabbithole, catered specifically to an audience whose world will be laden scores of open tabs, powered by a powerful thumb capable of marathon scrolling.

Horowitz refrained from naming and shaming any author in particular, but we need not be as courteous. Let us examine the aforementioned Walliams — currently considered one of the UK's best-selling children's authors, albeit minus the global tidal force that was JK Rowling. I have here before me a sample from his collection of short stories, The World's Worst Children 2 (2021), although it is impossible to convey the full visual kaleidoscope in mere text without the array of font sizes, illustrations and random bold items Walliams has at his disposal:

"Creepy-crawlies are called creepy-crawlies for a reason. They are creepy and they are crawly. Slugs, worms, spiders, caterpillars and cockroaches are creatures that give most people the creeps. Not Griselda. Griselda was a girl who loved creepy-crawlies. If she saw a worm wiggling around in the mud, she would pick it up and put it in her pocket."

Contrast this with Kaye Umansky, a children's author in the '90s whom almost nobody has heard of. Here is a short sample from Pongwiffy and the Holiday of Doom (1995):

"Poor Scott. The world of show business is fickle and things hadn't been going at all well for him lately [...] The punters had stayed away in droves, and the film had broken all box office records with the lowest ever takings in history. Since then, he had been what is commonly referred to in show business circles as 'resting', which in all other circles means out of a job."

Sucking out the joy

It is unfair to condemn one and laud the other on the basis of scant lines, but rest assured that you can consider this application of wit and sentence structure as an accurate snapshot of their respective magnum opuses. Just like Walliam's fictional world encompasses a wild imagination (we cannot fault him for his stories the way we can for his liberal use of visual aids or short sentences), Umansky's repertoire is also filled with wild plotlines involving witches, vampires, goblins — but richly told via an almost Jane Austen-esque humour to keep parents hooked.

However, because Umansky's prose remains trapped within pages absolutely riddled with text and very few pictures, her books may as well be invisible to an enquiring child. I know this because at a local school, one librarian who wished to remain anonymous (for reasons that will soon become clear) said, "Take the whole Pongwiffy set if you really want, but don't tell anyone at school I'm just giving it all to you — we were getting rid of them anyway because they've just been sitting there for about 10 years."

Is it because fewer than ever parents are reading to their young children now? Has the task of learning to enjoy fiction been unceremoniously dumped upon an eight-year-old's unwilling shoulder without a guiding hand? Or do publishers simply need to work harder than ever (snappy sentences! Lots of colour!) to stand out as books become a dying breed?

One particular literary agent told screenwriter Cairo Smith (who promptly complained on X, as he well should) that teenagers can no longer understand a third person omniscient style. Are teenagers really this uncomprehending and unforgiving? Or is it because no publisher can risk losing to the seductive powers of social media? There are no easy answers — but how sad would it be if the adults of tomorrow have no literary childhood heroes to return to when they are in desperate need of a restorative hit of nostalgia.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ