Glass ceilings in governance hold firm

Federal and provincial cabinets, the core of decision-making, remain male-dominated

Karachi

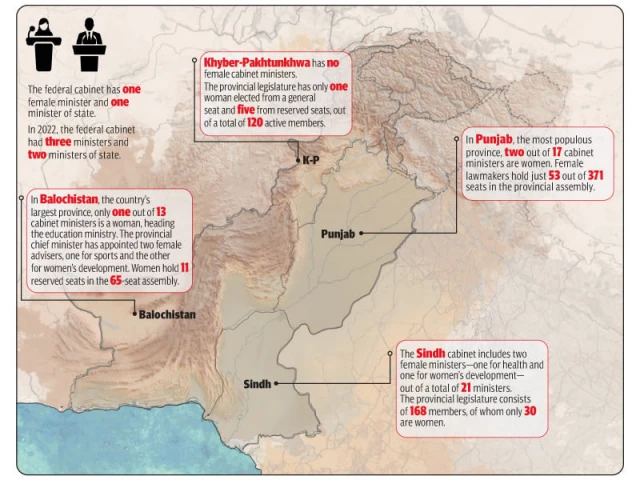

Democracy, at its core, is meant to uplift the powerless. In Pakistan, it does the oppositereinforcing the dominance of those already privileged. Little wonder, then, that political leadership remains a men's club, while the brilliance of half the population is confined to handling household ledgers and flipping through fabric swatches. This imbalance is evident in the federal and provincial cabinets, where women hold a token presence. At the federal level, they occupy just two positionsone minister and one minister of stateamounting to a mere five per cent of the cabinet. In the provinces, female representation is just as limited, averaging less than 10 per cent.

Yet, despite making up half the population, women remain largely shut out of the country's corridors of power. In Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (K-P), home to nearly 20 million women, the provincial legislature has 120 active membersyet not a single woman holds a cabinet position. The assembly does have a female deputy speaker, but only one woman has been elected on a general seat, while five others occupy reserved seats. Sindh, where women number over 26 million, fares only slightly better. Of its 168 assembly members, just 30 are women, and only two have cabinet roles. Punjab, the most populous province with nearly 63 million women, has a female chief minister, yet women occupy only 53 out of 371 assembly seats and hold just two cabinet positions. Balochistan, the largest province by land area, offers an even bleaker picture. Out of its 65-member assembly, only one woman serves as a minister, while 11 others hold reserved seats. The deputy speaker is also a woman, but beyond that, female leadership remains scarce.

According to Mumtaz Mughal, Director at the Aurat Foundation, despite women constituting 50 per cent of the country's population, their representation in the national and provincial assemblies has barely reached 17 per cent. Mughal believes that the high cost of elections, the large size of constituencies, the exclusion of rural women and the sexist attitudes of political parties led to women's low political participation.

"We had demanded 33 per cent representation for women through a formal proposal recommending the allocation of alternate constituencies for women to enable their direct participation in elections both in 2018 and 2024. However, due to the weak commitment of parties, even the condition of 5 per cent tickets was not fulfilled during the previous elections," lamented Mumtaz.

Fehmida Riaz, a Karachi-based women's rights activist and member of the Women's Action Forum (WAF), highlighted the low political participation of women in Sindh. She argued that their representation in the Sindh Assembly is largely symbolicdespite holding 16 per cent of the seats, their role in legislation and government formation remains negligible.

"All government departments, barring a few, are led by meneven those meant to serve women," Riaz pointed out. With such minimal representation at every level, their voices, she said, are inevitably shut out of policymaking. "Even when laws protecting women's rights are passed in the Assembly, meaningful implementation at the grassroots remains elusive," she cautioned.

Her words reflect a broader realitywomen in Pakistan rarely hold positions of real political influence. Yet, against these odds, some defy the norm. In a recent conversation with The Express Tribune, K-P's Deputy Speaker, Suriya Bibi, took pride in securing a general seat against 12 male candidates. "This is a breakthrough for women in a male-dominated political arena. The idea that women cannot succeed in a patriarchal society is outdatedmy victory proves that voters trust female leadership," she asserted.

While Suriya's win is a silver lining for aspiring female politicians seeking to challenge the androcentric nature of governance, it remains an exception. Women's ascent to power in Pakistan is still an anomaly, their leadership constrained by preordained roles. Acknowledging the grim gender disparity in the K-P Assembly, Suriya questioned how women's voicesdespite comprising a significant portion of the populationcould be heard when their presence in decision-making was so marginal. "If we aren't represented, how will our parliamentarians fight for our rights?"

Systemic exclusion

A matric student memorizing the complex chain of events leading to the independence struggle and the bloodbath of partition would unwittingly learn one crucial lesson about gender and politics – men shape history while women mourn its consequences.

After a group of men demarcated the boundary between Pakistan and India through the Radcliffe Award in 1947, millions of women were suddenly left exposed to rampant abductions, sexual violence, and other atrocities. Some lost their families and homes – others were stripped of both dignity and sanity. Yet none had a say in the political decisions that reshaped their lives forever.

According to Zahra Sabri, a Karachi-based activist and academic, the historic role of women in political movements in the subcontinent has been quite weak and has not been representative of their numeric status. "Today, this explains their underrepresentation in the legislative bodies and cabinets," explained Sabri.

"Historically, women have been treated as subordinates. In the past, women played a role in politicsas long as they stayed out of mainstream power. Figures like Begum Ra'ana Liaquat, Begum Jahanara Shahnawaz, and Begum Shaista Ikramullah were active but never held real political power. Hence, they were allowed their own spaces and platforms. Otherwise, men have never truly relinquished control," said Zubeida Mustafa, a veteran journalist.

Expanding on women's political underrepresentation, Zohra Yusuf, former chairperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan opined that Pakistan had followed a trajectory of regression when it came to women's political rights.

"Since the revival of democracy in 1988, women's leadership abilities have been viewed scornfully. While the PML-N is historically known to be male-dominated, sadly this time the PPP in Sindh, going against its previous record, has also ignored women. There are only two women in the Sindh cabinet, and one is Dr Azra Pechuho, who is the President's sister. There is certainly a lack of political will," noted Yusuf. This lack of political will, however, does not mean past regimes made a sincere effort to empower women. Even during former military ruler Pervez Musharraf's tenure, policies that seemingly expanded female representation were less about gender equality and more about political necessity.

Capturing the irony, Mustafa said, "When Musharraf introduced the requirement that all lawmakers must have a degree, they couldn't find enough men who met the criteria. And so, the very men who had long kept women from the corridors of power ushered them innot as leaders, but as placeholders. Even in Parliament, they remained tethered, their voices echoing not their own convictions, but the dictates of fathers, brothers, and husbands. Their seats were theirs in name alone -- real power lay elsewhere."

Tokenism and dynastic politics

"Men with political power cling stubbornly to their dominion, resisting any real shift in the gendered order of governance. When women manage to wedge a foot in the door, forcing their way into senior cabinet roles, the political elite respond not with acceptance but containmentappointing them to ministries that, in their shrunken, masculinized imagination, seem less consequential."

In an interview with the Cambridge Journal of Law, Politics and Art, American feminist political theorist Cynthia Enloe, discussing her book The Big Push, laid bare this patriarchal sustainability formula. Spheres like health, education, and the environment are "feminised," handed over to women, while the weighty affairs of defence, interior, and finance remain tightly gripped by men. The same pattern plays out across Pakistan's cabinet positions. "I would not hesitate to call the decision-making structures in Pakistan misogynistic. There is a lot of lip service to women's equality and rights but tangible steps in accepting them as equals in leadership positions is clearly lacking. Pakistan's political leadership is, in fact, somewhat like the elitist clubs that still keep women out. When given a chance, women have proven to be more effective parliamentarians," said Yusuf.

Nevertheless, women's capacity for making meaningful contributions to the domain of governance ultimately boils down to whether or not they are given the opportunity to freely voice their opinions when in a position of power. Hence, when the majority of female incumbents are appointed on the basis of tokenism, it is unreasonable to expect any real change in the androcentric nature of politics.

"Women have never truly been given power. Even when we speak of Pakistan's first female prime ministershe had to marry Asif Ali Zardari to craft an image that fit the political template. In many areas, she appeared to lack real decision-making power, often deferring to her husband, who played a dominant role in her administration. When it came to day-to-day governance, I wouldn't say she was a particularly strong leader at the time. This pattern has existed throughout our history, and we have to acknowledge it, no matter how we frame it," Mustafa noted, unveiling the layers of power.

Building on Mustafa's argument, Sabri observed that the presence of female heads of state in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka owed more to the endurance of dynastic politics than to the dynamism of the women themselves. "Each and every woman who became a head of state among the mentioned South Asian countries did so by riding on the credentials of a male relative." While Sabri pointed to the dynastic nature of female leadership, Professor Anoosh Khan, Chairperson of the Gender Studies Department at the University of Peshawar, underscored another structural limitation the lack of autonomy for women selected through the parliamentary quota system.

"Once women are in parliament through the quota system, their voices are often silenced since the party leadership dictates their stance on bills, and they cannot speak out against the party's agenda. While women's representation in parliament is important, it is not enough to assume that simply having women in the room will lead to progress for their gender, until or unless they have the opportunity to voice their concerns and contribute meaningfully to policy decisions," opined Dr. Khan.

She concluded with a call for equal opportunities in politics, stressing that women's presence in decision-making bodies must go beyond symbolism.

One step forward, two steps back

Decades after electing its first female prime minister, Pakistan still treads the path of belated milestonescelebrating 'firsts' for women in halls of power, from the Supreme Court to the National Assembly, and now, for the first time, at the helm of its most populous province.

"It's the same old performancejust a way to show how progressive and inclusive we are. We celebrate milestones like the 'first female prime minister' or the 'first female Supreme Court justice,' but none of these leaders have actively worked towards structural change. It's about optics, not real commitment," called out Mustafa.

Echoing this sentiment, Yusuf described women's political representationparticularly in cabinet positionsas a frustrating cycle of progress and regression. "Even the misogynistic PTI government had several women holding important portfolios in the federal and Punjab cabinets. Now, instead of inching forward, we are witnessing a sharp decline. When women are perceived and treated as second-class citizens, it's hard to imagine them climbing the rungs of political leadership," observed Yusuf.

"I have often argued that parties can show magnanimity and put women up as candidates for general seats in constituencies where their win is assured. For instance, the PPP on a Larkana or Nawabshah seat and the PTI on any K-P seat. Women who are currently in leadership positions such as Maryam Nawaz, owe their status to their families, although along the way they may develop qualities of their own," noted Yusuf.

Women's inclusion in politics

The first step toward gender inclusion in politics is to expose its glaring absence in state structures. Yet, reflecting on past trends or dissecting present practices amounts to little more than an academic exercise unless it is met with a genuine commitment to reshaping the futureone where women's political participation is not just acknowledged but actively championed.

"Change has to start somewhereit won't happen overnight. In some Nordic countries, a minimum 40 percent representation for women was introduced, and now they have even more women in politics, despite shifting toward right-wing policies. Someone has to take the first step," Mustafa insisted, her voice carrying both urgency and hope.

But to Yusuf, there is no step forwardonly the ground slipping away. "In all my years of activism, from the late '70s to the present, I have never felt such a sense of despondency. We are not making progress but witnessing a sharp decline. The political situation is intrinsically tied to women's rights and status in the country, both of which are deteriorating," she said, the weight of experience evident in her words.

Mustafa, however, refused to accept that decline as irreversible. "My answer is always the sameeducation. We have systematically neglected it because it allows for exploitation. Without education, without critical thinking, people can be deprived of what they deserve. If we had a well-educated society, people would demand equality. But the very concept of equality is missing from our system. Even in our textbooks, there are barely any chapters about women or by women," she argued, the frustration evident in her tone.

Knowledge, Sabri contended, was only half the battle. "For decades, universities and the education system have produced dynamic and capable women and men. But where do these meritorious graduates end up? Most either leave for the diaspora or settle into private organizations. Few ever reach Parliament or the cabinets," she said.

Until the political culture shifts and the road to power becomes more meritocratic, Sabri argued, it matters little how many competent women emergebecause the system itself remains unwilling to accommodate them.

And so, the debate circled back to the inescapable reality. "In the end, it's always about power," Mustafa concluded, "and that power ultimately remains with men."

With additional contributions from Wisal Yousafzai, Razzak Abro, Muhammad Ilyas, and Mahnoor Tahir

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ