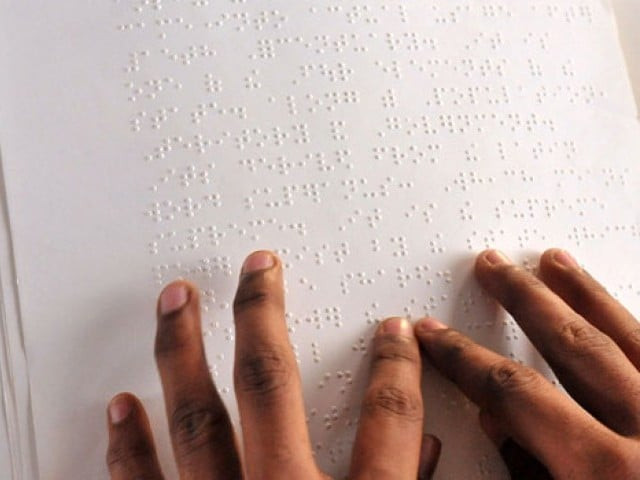

Braille labels missing on medicines

Without Braille, visually impaired patients can't identify names or dosages of prescribed medications

Imagine waking up one day to find yourself surrounded by complete darkness. Darkness which refuses to disappear with the flicking of a light switch or the pulling of a curtain. Such is life for nearly two million blind people in the country, who rely entirely on their tactile senses to navigate through their day. While a person with visual impairment might be able to switch on the television or fan thanks to their routine familiarity with their spatial surroundings, when it comes to taking medications, there is no way for them to differentiate between a box of painkillers and rat poison.

All across the globe, Braille labelling, which allows people with visual disabilities to trace out words through strategically raised dots, is widely used across the goods, services and public sectors, in an attempt to allow the differently-abled community to independently engage with the world on equal footing. Unfortunately, in Pakistan, apart from little or no census data on the blind community, Braille labelling is entirely missing on the packaging of drugs produced by commercial pharmaceutical companies, which despite earning trillions in revenue, turn a blind eye to the special accessibility needs of people with visual disabilities, who are unable to accurately identify the name, dosage, and expiry date of a prescribed drug and are hence denied safe medical treatment.

Shahida Ahmed, a blind woman, suffering from diabetes poured out her struggle to buy and administer her medications in the absence of Braille labelling. "When I went to the pharmacy to purchase my medicines, I was mistakenly given a medicine from some other brand. Although the pharmacist immediately informed me of the error, I still wished I could independently identify my medications without having to rely on someone's goodwill," bemoaned Ahmed.

While Ahmed's pharmacist was considerate enough to assist her in buying the correct medication, the world is not as kind for the majority of blind people. For instance, Hafiz Muhammad Arif, another blind citizen was shamelessly given the wrong medication by a callous medical store owner. "I went to the pharmacy seeking relief for an upset stomach, but the pharmacist gave me a laxative which aggravated my diarrhoea. Many a times, pharmacists joke that they can give us any medicine, and we'll know what it was after using it," sorrowfully expressed Arif.

"When buying medicines, visually impaired people must either rely on a relative or friend, or trust the pharmacy owner since crucial information about the medication is not provided on its packaging in Braille," lamented Muhammad Saleem, a blind teacher.

Seconding Saleem, Ibrahim, an elderly blind retiree believed that if Braille language was used on medicine packaging, blind people could buy their medicines without anyone's help. "Sadly, it is a misfortune that the government does not consider special people as citizens of this society," riled Ibrahim.

According to Muzaffar Ali Qureshi, President of the Pakistan Association of the Blind, authentic data on the number of blind people in the country could not be compiled since the establishment of Pakistan. "Therefore, it is not known at the official level the exact number of blind people across the country," questioned Qureshi.

Mohammad Shahnawaz Munami, the country's leading ophthalmologist, estimated that more than two million people were suffering from blindness in Pakistan, which is usually caused by congenital vision loss, cataracts and diabetes. "Braille on medicine packages ensures that visually impaired people can identify the name, dosage and expiry date of medicines. Many countries now require pharmaceutical companies to include Braille labelling on drug packaging to comply with disability rights and health regulations. Unfortunately, there is no Braille labelling on pharmaceutical products manufactured in Pakistan," confirmed Munami.

"Pharmaceutical companies do not use Braille language on their medicines and it is a pity that the government also does not take any action in this regard," regretted Rana Asif, Head of the Law Department of the Disabled Welfare Association.

This is despite the fact that the sale of medicines in Pakistan is expected to exceed Rs8.5 trillion towards the end of 2024, with the annual growth rate of local pharmaceutical companies ranging between a minimum of 11 per cent to a maximum of 295 per cent. Furthermore, the largest local pharmaceutical company's sales stand at approximately Rs51 billion with an annual growth of 25.47 per cent.

Noor Muhammad Mahir, President of the Pakistan Pharmacists Legal Forum, highlighted the fact that drug manufacturing companies in Pakistan failed to provide crucial medication details in Braille, unlike many other countries where medical information and prices were readily available in the tactile language for the visually impaired.

In fact, as per revelations made by officials from the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan, the incorporation of Braille on the packaging of medications is not part of the provisions of the Drug Labelling and Packing Rules of 1986, which have not been updated since.

"The fact that there are no special arrangements for the blind in Pakistan reflects that these people have no importance in the eyes of the government," commented Dr Nasreen Aslam, Professor of the Department of Social Work at the University of Karachi.

In addressing the backlash, Asim Rauf, Chief Executive of DRAP and Azhar Saleem, Punjab's Chief Drug Controller assured that the suggestion would be conveyed to the federal authorities to include Braille on the packaging of medicines for the blind.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ