On February 21 each year, International Mother Language Day is celebrated globally under the auspices of the United Nations (UN).

The day has been celebrated yearly since 2002. For every year, this day is linked with a theme. This year (2023), the theme is “Multilingual education – a necessity to transform education”.

Under this theme, special emphasis on indigenous people’s education and languages is called for.

All over the world experts agree that mother tongue is valuable due to several reasons. Mother tongue is vital in children’s cognitive development as well as reasonable thinking and emotional balance of people.

Being fluent in the mother tongue, alternatively known as the native language, benefits the child in numerous ways. It connects him to his culture and helps in learning other additional languages.

Researchers are showing concern that children across the developing world are learning very little in school, a reality that can be linked to teaching that is in a language they do not fully understand. It is a practice that leads to limited or non-existent learning and acquisition of knowledge and skills, alienating experiences, and high drop-out and repetition rates.

To improve the quality of education, language policies need to take account of mother-tongue learning. Models of education which ignore mother tongue in early years may prove unproductive and ineffective, having a negative effect on children’s learning.

Mother-tongue education, at least in early years, can enable teachers to teach and learners to learn more effectively. An oft-quoted sentence of great Nelson Mandela is, “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart”.

Studies have reported evidences on how language of instruction can adversely affect children’s learning, if the preferred language is not their mother tongue.

Some of the highlighted issues include a) Children in rural locations are much more likely to drop out of school unless they can learn in their first language. b) In all settings, children perform worse across the curriculum when their first language is not used to teach. c) Children do badly in a national or an international language which is used for teaching, if they do not use it at home. d) Children never become fully literate if they do not already know the language of literacy well. e) Children may never make it into secondary education if they struggle with language in primary school, even though by their teens their ability to learn advanced second language might be greater. f) Groups who do not have easy access to dominant languages will continue to see their interests as not being served by the state. g) If school assessments are conducted in a language that a child does not understand well, it will be impossible to get a picture of their real capacities and to judge school.

According to Unesco, 40% of people have no access to education in a language they understand, and 617 million children and adolescents do not achieve minimum proficiency levels in reading.

In an essay on “The educational and economic value of embracing people’s mother tongues”, published in London School of Economics Business Review in 2018, the issue has been highlighted with

examples from different countries. With regard to Pakistan, it says that Pakistan’s children are taught in their national language, Urdu, that has origins outside the country and is only spoken by around 6% of

the country’s people.

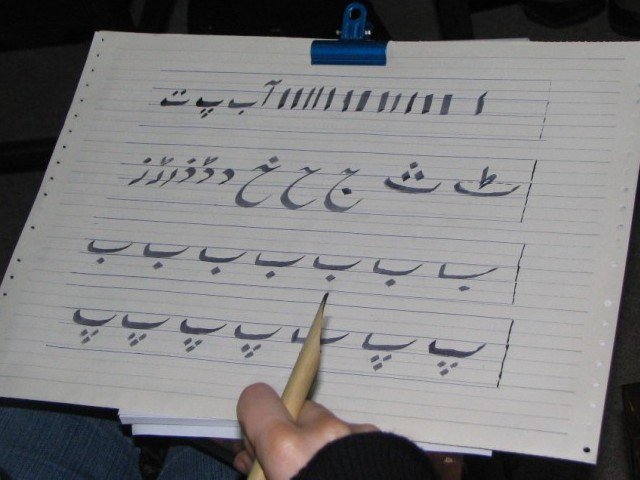

In Pakistan, about 74 languages are spoken. Besides Urdu, the national language, major provincial languages are Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto and Balochi. Some other familiar languages include Saraiki (Southern Punjab), Brahui (Central and Central East Balochistan), Shina (Gilgit-Baltistan), Kashmiri (Azad Kashmir) and Hindko (a part of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa).

Still other minor local languages, among many, may be cited as Balti, Bhaya, Dari, Dogri, Gujrati, Gugari, Kohistani, Marwari, etc.

Urdu, however, serves as lingua franca in Pakistan. Although in remote rural areas, a majority is unable to read or write in Urdu, it is understood easily across country to the extent of communication.

Medium of education is mainly Urdu in public educational institutions up to almost 12 years of education. In private schools, English is used from the very beginning.

At graduate level and beyond, English remains the main medium, both in natural and social sciences. Local languages and mother tongues are hardly taught formally at any stage.

With the advent and rapid proliferation of information technology, artificial intelligence and robotics, only a functional and operational monolingual system of communication will be required in order to get the jobs done.

However, such privileges will not be available to all, timely and equally. This will further put population factions proficient only in their mother tongues to great disadvantages.

The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, “a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity”, comprises 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These goals are indivisible and encompass economic, social and environmental dimensions.

SDG 4 focuses on education and aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. Patronising education using mother tongue can be used as a tool to achieve the SDGs.

Mother-tongue education plays a vital role in the development of personal, social and cultural identity. It is advocated by experts as an indispensable instrument in achieving the SDGs.

Mother-tongue education enables better understanding and transfer of the structure of language to several new languages, which flows down into the entire socioeconomic fabric. It also helps in other essential skills, such as critical thinking and literacy skills.

Local businesses, industry and trading are greatly culturally oriented. Proficiency in local mother tongue aligned with modern technological skills can benefit these economic units immensely.

In rural areas and small towns of Pakistan, this is essential for the provision of education, employment and livelihood and can be a meaningful step towards poverty reduction. This objective can be achieved through qualitative and quantitative teaching of the mother tongue.

THE WRITER IS EX-JOINT ECONOMIC ADVISER TO THE GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, NOW A FREELANCE CONSULTANT

1732003896-0/Zendaya-(1)1732003896-0-165x106.webp)

1731914690-0/trump-(26)1731914690-0-165x106.webp)

1732003946-0/BeFunky-collage-(70)1732003946-0-165x106.webp)

1731749026-0/Copy-of-Untitled-(3)1731749026-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS (7)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ