Politics in chess: Checkmate

Dramas of Pakistani cricket pale in comparison to the soap opera that is chess, according to this chess champion.

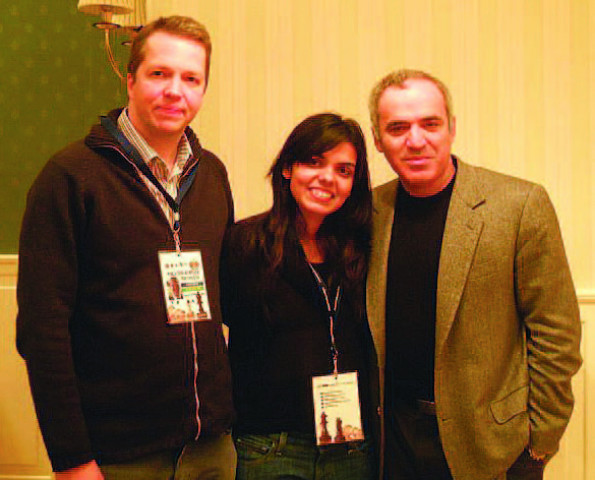

I am sitting across the table from Nida Siddiqui, the women’s chess champion of Pakistan, at her home in Karachi. A chatty 23-year old, she laughs a lot, her eyes shining with intelligence. Nida won the national women’s chess championship in July 2010. “So, is that the first time you won the women’s title?” I ask, as we continue playing and my hands reach for my embattled knight.

“Well, there have only been two national championships,” she replies. “There was one in 2000, and the last one was in 2010.” She tilts her head, and goes on half-jokingly, “There was a 10 year gap in between tournaments. There was lots of interest in Pakistan, but sadly the person who organises most of the championships happened to be the husband of the winner of the 2000 national championship, Zinobia. Who wouldn’t want his wife to keep the title for 10 years?”

And you thought Pakistani chess would be a relatively sedate sport — seems like you can’t escape politics in Pakistan, even in chess. The next women’s championship is, apparently, due to take place next year.

Nida’s chess talent was discovered early on in her childhood, and she tells me how grateful she is to her family for supporting her, by sending her to international chess camps at an early age. But that is not Nida’s only talent — she also recently graduated from Sindh Medical College as a doctor. Juggling her demanding medical career with this cerebral pursuit can be a bit tricky at times, but Nida says, “I start practicing for an hour a day about 15 to 30 days before a tournament. While the chess didn’t affect my studies very much, my grades did go down a little. But I don’t regret my chess at all.”

When I study the chessboard, she is up by several pieces.

Nida talks readily and excitedly about her experiences abroad, and generally she has been received well internationally. “They really encourage the fact that there is a female from Pakistan. But they often ask me if I am allowed to leave the house without covering my head, given the Taliban threat. They really admire the fact that I have the courage to come overseas and play on my own.”

Back in Karachi, the local chess scene is active, if not exactly thriving. At the Karachi Open tournament anyone who can pay the entry fees can take part. But this outspoken player has found herself embroiled in a controversy with the tournament organisers. She was told by journalists on two separate occasions — one was during a TV interview — that the Karachi tournament organisers claim that she told them that she doesn’t take part in “kachra tournaments”. Nida claims she never said anything of the sort. In fact, she says, no one bothered to call her or send an invitation. “Excuse me, I don’t have an ego problem, but I am the women’s champion. They just have to call me with a formal invitation, and I will come.”

Other than the national championship in 2010, the last local tournament Nida played was in 2005. While such tournaments do help her game, the atmosphere can often be far from ideal. “I like playing in local tournaments, except for the fact that they don’t provide you with a very healthy environment. For example, you are concentrating on your game, and someone is shouting over your head asking when they will get some chai,” says Nida.

I make my move on the chessboard, confident that it is a good one, because her hand is on her chin, and she is staring at her pieces. When she responds, I end up losing two pieces for one of hers. But chess is not just about complex strategies and patient contemplation — the atmosphere in the tournaments, according to Nida, can be dauntingly testosterone-charged, and often blatantly sexist.

“There is a particular group of people, who discourage chess amongst women. They will taunt you by saying, only women can play such terrible chess, and even if you make the right move during a game, you start doubting yourself,” says Nida.

Compare that to the rules followed in international tournaments where there is no talking and by no means are you allowed to distract your opponent. In 2008, Nida took part in the 38th chess Olympiad in Germany, and scored six of the 10 points made by team Pakistan. When she came back, her enthusiasm for chess was put under check. “I was playing at a local Karachi club against an experienced player, and he taunted me by saying, ‘You learned this from Germany?’” says Nida. “And I was still playing. Show some class! And I am talking about good local players here.”

This lack of professionalism rightly disturbs her. For a woman to hold her own in such an intimidating environment is an achievement in itself. Many, in fact, break down. “I was playing during the qualifiers once, and one girl was losing, and everyone could hear her sobbing. Bichari,” says the confident, opinionated player, for whom the possibility of ever breaking down in such a manner seems unlikely.

I look at the chessboard, and realise that I’ve been clearly beaten. I put my king down in surrender, as our conversation returns to the competitive world of the women’s chess circuit.Nida praises the Pakistan chess federation for sending players to the Olympiad in Russia, despite being underfunded and barely active. “When I wrote to the president, Altaf Ahmad Chaudhary, he supported me competing in Lebanon,” says Nida. “And when I said that it was time Zinobia defended her title after 10 years, he organised the tournament in a very small budget, with significant prize money. I really appreciate that.”

A patriotic woman, Nida considers anyone representing Pakistan to be an ambassador for the country. During the Olympiad in Russia, where there were chess teams from the world over, she talks about how Ghazala, Pakistan’s number 3 flouted the rules: “The game was over, and the captain told her to stop playing but she kept making her moves. When the captain dropped her from the next game, she went to the other teams and told them that she hoped Pakistan would lose, and that her team was jealous of her. So, people were laughing at Pakistan in that tournament.”

Nida raises her voice “It’s like in cricket, if for example, Shahid Afridi drops Shoaib Akhtar, and then Shoaib Akhtar goes to the Indian team and says, I really hope they lose, because they are jealous of me.”

If Nida is fearless in her criticism, it is because she is confident about her game: “I call it like I see it. If I don’t, then how would I be different from anyone else? But as far as my performance is concerned, I do carry my weight; I do score points for Pakistan in tournaments.”

According to Nida, “You are only a high class player, when you deal with time, bad positions, good positions, your opponent, and if you can play under pressure.”

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, August 28th, 2011.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ