Inside the journey to escape Ukraine

How a group of foreign students endeavored to evacuate the war-hit Eastern European country

When Ehteshamul Haque bid farewell to his family in Dera Ismail Khan and boarded a Ukraine-bound plane in the winter of 2020, a lot was on the cards for the medical student but a war that would leave him beseeching his statesmen for emergency evacuation.

Even until a week ago, when the chatter about a possible Russian invasion was starting to fill the air in the city of Kharkiv, and civilians were picking up batons, he had hoped for it to pass.

“We had contacted the Pakistani embassy, they reassured us that everything was fine and that there were protocols in place if the situation escalates. We asked the university if we could go back home and take our classes online, but they too told us to stay put and that there was nothing to worry about,” he recalled, wheeling his luggage through a packed metro station that had now become a bomb shelter for thousands of people trying to escape the Russian airstrikes.

The night of horrors

Although one could smell the tension suspended in Kharkiv’s air days ahead of the conflict, the war entered the city on the morning of February 23rd, when a blast in one of the military bases close to the city rattled Ehtesham’s apartment.

“We were still uncertain about how bad things were, but Kharkiv is just 40 kilometres from Russian soil and surrounded by military bases, so we knew we were in the eye of the storm,” said the student, relentlessly dialing the emergency hotlines issued by his embassy, after being cooped up for several hours in the metro station, but all at vain.

When the realisation of the crisis slowly dawned, what many foreign students like Ehtesham needed to get through the ghastly night of February 23rd, was the comfort of community. “Everyone is too scared to be alone tonight, so people are trying to stay in groups, in case something goes bad,” Priya, an Indian student, recalled updating her family back home over WhatsApp, adding that she’d called her Pakistani friend Areej to stay over with her.

The journey to Lviv

The next day, on the 24th of February, as news of Moscow’s attack made headlines around the world, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy announced martial law across the country. Ehtesham, Priya and Areej, who were all students at the Kharkiv National Medical University, were now made aware of the full-scale attack on Ukrainian land and had been instructed to take shelter in bunkers and underground stations until further notice from their embassies.

According to text messages exchanged between Priya with her sister in Delhi, the Indian embassy had also been hard to reach, offering little to no help in translocating students from conflict-ridden Kharkiv to safety. “I am scared. We are being asked to walk 20 hours by foot, but it’s not safe out there, and the sirens are constantly blaring to warn us of airstrikes,” she had told her concerned sister.

On the other hand, the Pakistani Embassy had issued directives for Pakistanis to turn to Ternopil in Western Ukraine, which is 900 kilometres from the city of Kharkiv, via a tweet. “Ours was the worst-hit city, so getting out of Kharkiv was the main problem. All buses and trains were overbooked. We had no way of going anywhere and no one at the embassy was receiving our calls,” said another Pakistani student, who had been stuck in the metro station without any arrangements for food or water.

After almost a day of staying put in the makeshift bomb shelter, a WhatsApp message on a South Asian students’ group had alerted Ehtesham and friends that the airstrikes were soon to target civilian areas and that Kharkiv had been compromised. However, public transport was still unavailable and the embassy had now asked students to change their course to Lviv, a city near the Polish border, from where they were eventually going to be shuttled to Poland.

It was evident now that getting on a train would have to be by force. After eight hours of relentlessly trying, a few students including Ehtesham were able to push their way into a packed coach, that was several hours late and took another 18 hours to reach the destination.

While at the same time, students from other cities like Ternopil and Kyiv were also beginning to pour into the city of Lviv.

“In our correspondence, the embassy had told us that there would be buses ready for us in the city centre,” shared Taimoor, who had escaped the Ukrainian capital amid what he described as “fire raining from the sky,” and landed in Lviv. From there, he joined the other students, on a 35-kilometre trek to the border site, that took almost eight hours in extreme weather, without any food or water, as wartime sirens blared in the distance.

The chaos

According to Kainat, a student who’d covered some 128 kilometres coming from Ternopil to Lviv, and then over 35 kilometres on foot to the border region, the evacuation site was no different than a warzone.

“There were immense crowds and we couldn’t locate anyone from the Pakistani embassy there to guide us, while the Ukrainian authorities were not letting us foreigners pass. All we could do was helplessly sit under the open sky for what seemed like an eternity until the day turned frigid, winds began to cut like glass and there was nothing to shield us from the weather,” she informed, adding that the food handed to them by Ukrainians living close to the border had also run out during the wait.

The government, in the meanwhile, had already issued multiple claims of immediate evacuation assistance, when news of stranded Pakistani students began to flood social media spaces back home.

“There are immense difficulties at border crossing points due to huge number [of people] wanting to leave Ukraine. Embassy and Ministry is actively engaging Govt of Ukraine to expedite the process,” read a tweet by the Pakistani Embassy in Ukraine.

Also read: Ukraine and Russia: What you need to know right now

Speaking to a state-owned broadcaster on the morning of February 27, Pakistan’s Ambassador to the Ukraine Dr Noel Khokhar assured that over 125 Pakistani students had already been safely evacuated from the Ukrainian border post, while over 378 were still waiting to cross over and 30 in transit.

“We have so far covered 80 per cent of our evacuation from difficult zones, but there is congestion on the border post and we are trying to facilitate the students,” he added.

In contrast, however, the students camped by the Polish borders alleged that they had received next to no help from their home embassy in getting here, and much of their evacuation efforts had been a test of self-endurance.

“In a matter of one night, we were told to pack our bags and traverse into uncertainty. All our essential documents including birth certificates and transcripts are still with our universities and we have no idea what the future would hold for us,” expressed a student from Kharkiv National Medical University, speaking on behalf of his cohort.

Making it to safety

It was after another night of waiting that Pakistani students including, Ehtesham, Areej, Kainat and Taimoor, were able to offer their worried friends and family some clarity on their evacuation status. The border finally appeared to be open, and queues of people were seen to be moving ahead. A few hours later, the Pakistani Embassy announced that it had safely evacuated over 606 students to Poland from Ukraine.

“Our phones were constantly ringing and some of us were down to our last bar of battery. The thought of losing contact with family was frightening on both ends, but we were relieved to hear that we could all cross over to Poland, despite being among the last groups as Ukrainians were given priority,” shared Kainat.

Also read: ‘198 civilians killed’ as Russian, Ukrainian troops come face to face in Kyiv

According to sources associated with evacuation services, however, the initial holdup at the border site had been created by Polish authorities, on suspicion that a group of Pakistani citizens who had initially crossed over was unaccounted for. “It then took some diplomatic efforts to convince Polish authorities to reopen their doors and let the remaining Pakistanis cross over,” the source claimed.

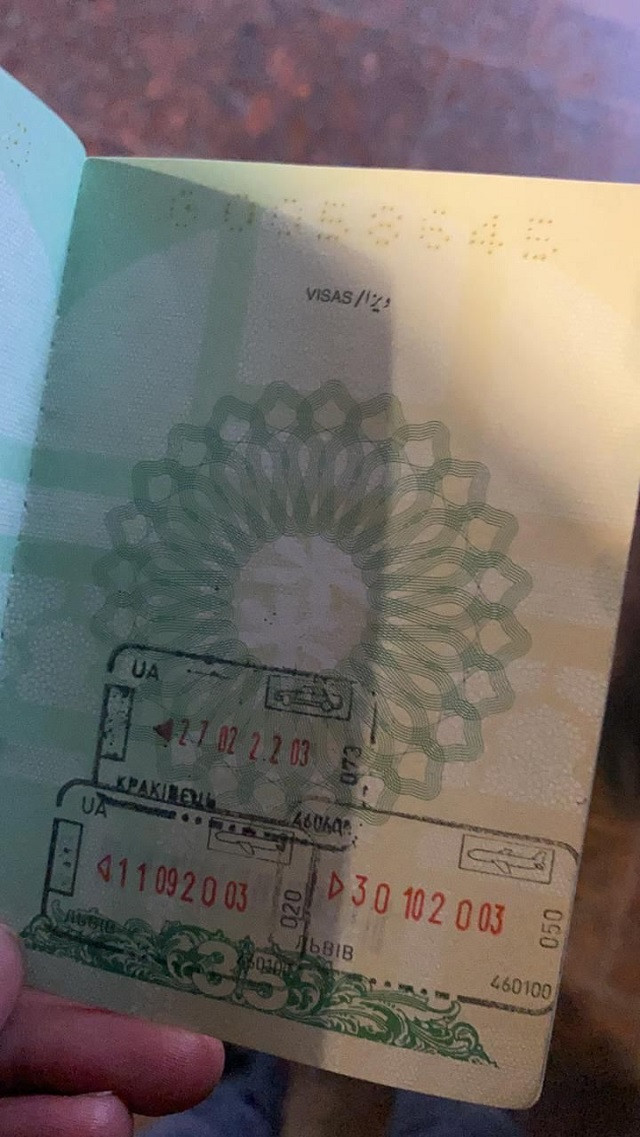

After what had seemed like an eternity of navigating a warzone, the students could now see themselves a step closer to safety. Per the last updates received, Kainat was issued an exit stamp on her passport at 6:30 PM on Sunday, along with Ehtesham and other students fleeing Ukraine. They were then shuttled to Poland’s capital of Warsaw for further evacuation to Pakistan.

At the time of this article’s conclusion, all named Pakistani students had safely reached Warsaw, while the Pakistani government had announced chartering the national-flag carrier to bring the students home.

However, some students alleged that getting on the plane has been an uphill battle so far.

Responding to which, Pakistan International Airline’s Head of Corporate Communications Abdullah Khan said that the Pakistan government has sought until March 1st to decide whether the plane would be required or not.

“A lot of students are still indecisive about heading home or waiting things out in Poland, while some have been citing permission issues from their university. However, we are ready to aid the students as and when needed,” he told The Express Tribune.

Disclaimer: Despite several attempts to contact the Pakistani Embassy in Ukraine for their statement on the matter, no word has so far been received.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ