China's mentally ill yearn to step from the shadows

Mental illness is rarely spoken about publicly, forcing millions to cope alone

For years, Shanghai artist "Cracks" has kept her diagnosis of bipolar disorder hidden from all but her closest friends and family because of a Chinese cultural stigma surrounding mental illness.

Despite mounting stress in a fast-modernising China, mental illness is rarely spoken about publicly, forcing millions to cope alone.

"They think we're crazy, that we can't assimilate in society, that we belong only in mental hospitals," said the 24-year-old, who asked for her real name to be withheld.

A previous work contract stated that any history of mental illness could result in dismissal.

So she hid her illness and the extreme mood swings it triggers in her, with lows that are "desperate, painful and hopeless" and laced with thoughts of suicide.

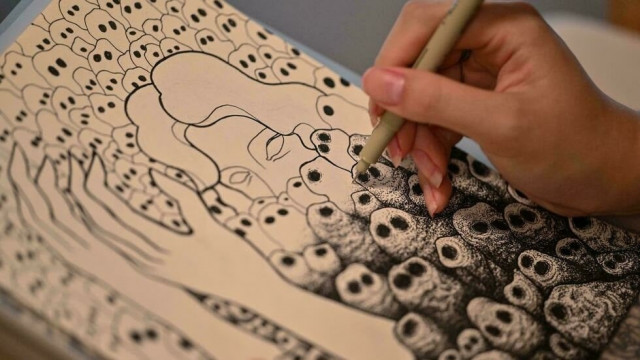

The pseudonym "Cracks" springs from her artwork, which she views as opening a crack to "let light in" to her life.

The black-and-white sketches portray a single female surrounded by clawing hands or sharp jaws. It's the only way to express her pain and "feel normal".

| Read More:Violence against women: a crime, societal failure or mental illness? |

Research published in The Lancet medical journal in 2019 suggested that more than 16 per cent of the population in China -- around 220 million people -- had experienced a diagnosable psychiatric disorder at some point in their life, and that the vast majority had never received any treatment.

The government last year signalled concern, pledging to increase awareness and treatment but providing few specifics.

Chinese culture still views mental illness as a shameful sign of weakness, said Chen Mengyuan, a social worker and the curator of a mental health-themed art exhibition in Shanghai displaying the work of "Cracks" and 80 other artists to raise awareness.

'We have to talk about this'

Shanghai psychoanalyst Luo Gaoyu said therapy in China remains in its infancy, with patients themselves often sceptical of its efficacy and wary of embracing it due to the stigma.

Treatment success is never guaranteed, she said, so societal acceptance is crucial.

Despite a younger generation slowly shining a light on the issue, there are still too few experienced mental health professionals, said Luo, 25.

"Having a small number of teachers bring up a large number of students -- that's fundamentally a problem," she said.

China must address mental health as an important part of overall public welfare, said a psychiatrist at a nationally recognised Chinese institution.

Otherwise, people "will not be treated, will continue to be in pain and unable to live and work well", said the doctor, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Pressures related to careers, the cost-of-living and other stressful issues are also mounting in rapidly developing China.

Young people are particularly vulnerable, often facing additional pressure from parents to buy a home and produce grandchildren, exacerbating issues like anxiety and insomnia, say experts.

"Young people in China are different from those overseas," often subverting their mental health needs to please parents, said Luo.

Chen, the exhibition curator, said that if they do open up to parents, "it is like admitting they are not an outstanding person, or not sound. Or they worry their parents may blame them."

"Of course, this is even less conducive to recovery."

Many elderly or rural Chinese still view psychological treatments with suspicion.

Luo said her own father looks down on her career, suggesting that she switch to something like the civil service.

His mother blames him, saying he had "chained himself up" in a cage of his own making.

"We have to talk about this," Chen said.

"If we don't, a whole group of people will never be seen."

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ