Sasha Sagan: The sense in science and spirituality

On Carl Sagan’s anniversary, his daughter Sasha discusses science, faith and family with The Express Tribune

Be it politics or sports, there are some whose path appears pre-determined just on account of a surname. And traversing it, as inevitable as the world can make it seem, paradoxically appears as an insurmountable feat.

Fans or colleagues, those around such individuals imbue moments of personal nostalgia – a shared experience between parent and child – with impossibly high stakes. DNA is not enough for the world to acknowledge your heredity. It demands an overt display that makes legacies built by sheer effort and will even harder to sustain.

Where science and ritual overlap

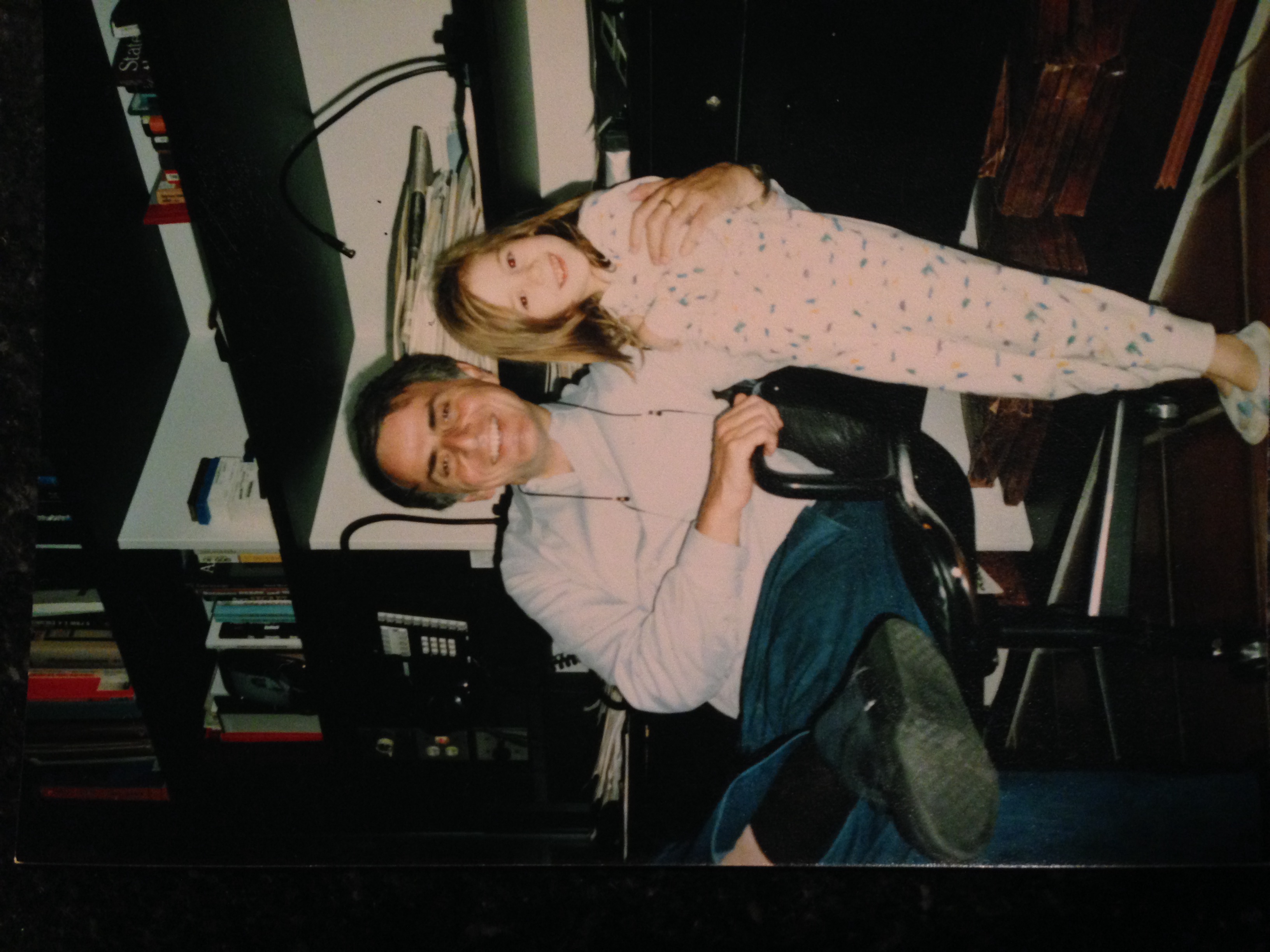

In her debut book, Sasha Sagan reflects on being raised by two 20th-century science heroes – the influential Carl Sagan and his better half Ann Druyan – without any sense of burden or urgency. In conversation with The Express Tribune, she seemed at ease with her surname as she goes about building family tradition in her own way.

“I think my philosophy is the same as that of my parents. I haven’t rebelled in that department,” she quipped. “No matter skeptical or orthodox your scientific worldview is, there is immense joy and revelry in life. I don’t think that diverges from how I was raised.”

Part memoir and part investigation into the mysteries of nature, ‘For Small Creatures Such As We’ reads like a soothing balm for those juggling life and ritual while making sense of the laws that govern our world and the universe.

“Finding a way to let our rituals and scientific realities overlap is important,” said Sasha, explaining that behind so many of our traditions is logic underpinned by science. “Different cultures and religions have coming-of-age rites, but they celebrate what is essentially a biological event: passing from childhood into puberty,” she elaborated. “Similarly, it is not just faith or tradition that governs many of our holidays. Hiding behind them is an understanding of equinoxes and axial tilt.”

While her clarity and simplicity hearkens back to her father, fervent rationalists could take issue with Sasha’s defence of a form of spirituality. Smiling at the notion, she answered: “My parents raised me with the philosophy that science is both a method of understanding reality and a source of awe and wonder.”

“Moments of discovery through the scientific method are indeed akin to spirituality,” she added. “The idea that a secret code in our blood ties us to our ancestors – that a lab can take a drop of our saliva and tell us who they were – is for me as magical as something out of a fairy tale. And yet, it is real and tangibly true.”

Although Sasha was raised with the understanding that science and a deep connection to the cosmos were never two different things, she admits that she did pine for celebrations all her life. “You need to see seasons change. Weddings and funerals are important markers in life, regardless of your beliefs or lack of them. We need momentous occasions and we need time to grieve and mourn,” she argued. “That is what I’m really interested in navigating.”

On death and parenthood

The title of Sasha’s book borrows a line made famous by her father in his groundbreaking TV series ‘Cosmos’. But as she reveals in ‘For Small Creatures Such As We’, it was actually, her mother Ann who came up with it.

That is just the tip of interesting anecdotes that pepper the book, however. Sasha lays out in vivid detail what being raised by true skeptics looks like. For instance, she narrates how she sought reassurance from her parents upon learning of the reality of death. “Promise me you won’t die!” a young Sasha would plead. While her mother would sweetly reply, “I promise,” her father would smile and say, “I’ll try my best.” “Such an accuracy zealot,” is how Sasha describes Carl in her book.

As heartwarming as these recollections are the fact that Sasha wrote the book while still pregnant with her daughter adds another interesting layer. Speaking to The Express Tribune, she admitted that getting married and embracing motherhood were crucial in inspiring her to make a case for rituals.

“It was certainly a cathartic experience for me. So many people around me in my age bracket have started to think about having children and are wrestling with the question of how to talk about death with them,” she said. “What are the traditions you want to be passed down and what you want to leave out? What do you emphasise and what do you value?”

According to Sasha, there usually isn’t much impetus to ponder on this while one is young and single. “It often starts with marriage. You make all these decisions planning a wedding – what the ceremony will say – and it’s this performance that opens a path from one reality to another,” she said. “Once you have children and they’ll ask such profound questions, how do you go about answering them? No one does everything prescribed by their belief systems to begin with. They all navigate traditions.”

Superstition, conspiracy and chaos

Sasha’s use of the word ‘spirituality’ comes with a caveat about its popular connotations. With so many in the West shunning traditional belief systems for equally esoteric ‘New Age’ ones, The Express Tribune asked her for her views on the future of rationality and ritual.

For her, the obsession with unscientific trends is a two-part issue that stems from a yearning to feel connected. “I think at the heart of it, those things that are not supported by science or are not evidence-based help people feel in an artificial way, connected to the solar system,” she said. “I relate to this urge, but in a scientific way. It’s sad that science just isn’t presented that way.”

“I also think that whatever the next thing is – whatever society moves towards in the next 500 and 1,000 years – it will be very difficult to invent something new and have it stick. So traditions such as Yoga may take on a secular incarnation, where people take up the meditative elements of it. But no matter how mutated, I think they will survive,” she added.

But what happens in cases where unscientific thinking becomes harmful to a society at large? What happens when it leads to communities like some in Pakistan that see vaccines or pandemic restrictions as some big conspiracy and jeopardise our collective well-being and safety?

“We, we have quite a few conspiracy theories and theorists here in the US so you’re not alone in that,” Sasha laughed. “I think there’s a natural urge to believe that someone’s in charge and in a weird way, people are reassured by the idea that there’s someone out there pulling the strings,” she said, explaining that such thinking trickles to other aspects of our lives until the lack of a safety net becomes our biggest fear.

“The original conspiracy theory in the US revolves around the assassination of JFK. I think people don’t want to believe that it was only one disturbed person who changed the course of history,” Sasha elaborated. “The idea that there is all this chaos without any safety is horrifying for many. I’m not saying there are no secrets out there in the world, but this general obsession is born out of fear of anarchy.”

How to make science attractive

Carl Sagan spent his entire life instilling curiosity, improving science education, and arguing with governments over issues like global warming and nuclear warfare. While he himself was always realistic about an average person’s capability of understanding the fine print of scientific ideas, how would he have reacted to the widespread Covid-19 deniers out there today?

According to Sasha, the biggest challenge in changing this mindset lies in making science education more engaging and attractive. “How do we get people to understand science beyond a list of formulas is a question that is as poignant to the United States as it is to the rest of the world,” she stressed. “In a perfect world, school teachers would earn huge salaries. Enough to draw people interested in their subjects from the private sector if need be.”

The next step concerns people’s approach to parenthood. For Sasha, parents should not be afraid to admit they don’t know something. “So often when a parent has some sense of insecurity or embarrassment due to lack of knowledge, their primary urge is to shy away from the subject. They want to present themselves as an authority,” she said.

“It is important, I think to let children know that you don’t have all answers. We ought to invoke a sense of curiosity among them that leads them beyond rote memorisation,” she added.

Science and religion in Pakistan

Ever since Fawad Chauhdry became the minister of science and technology, Pakistan has been oscillating like a pendulum between reason and tradition. The minister is adamant upon dissolving the Ruet-e-Hilal Committee, the body responsible for sighting the moon to mark the months of the Islamic calendar and in doing so, figure out when important Islamic religious festivals should take place. Fawad feels we no longer need a group of men to figure out something that can be easily deduced through technology.

Pakistan Ruet-e-Hilal committee chairman Mufti Muneeb-ur-Rehman. PHOTO: EXPRESS/MOHAMMED NOMAN

The Express Tribune asked Sasha what she made of this annual debate. “To me, it’s so beautiful. This is the intersection of centuries-old rituals and traditions, and real astronomy,” she replied with a smile on her face. “To me, they are not in conflict at all.”

Sasha added: “What is amazing is that religions in the world rely on the concept of prophecy to tell the future. But with astronomy in this case, it is literally prophecy that is accurate in letting you know the moon cycle.”

“We have this rock that orbits us and when it is full, it feels really sacred. To me, this is a beautiful dovetailing of science and religion. I’ll just say let the guys on the roof of the building do what they do. But is spectacular that we do really know what the moon will do next.”

What it means to be a skeptic

Every now and then, a throwback interview of Carl Sagan will open a debate on what a charismatic sceptic would make of unresolved scientific mysteries. As much as various media organisations try to sidestep them, the debate will ultimately find its way to his views on a higher power.

“No, I don’t think he would have ever considered himself an atheist,” Sasha said when asked what she makes of such arguments. “I don’t think of myself that way either.”

“Our views follow the logic of his idea about aliens. He would say, ‘I don’t have enough evidence and that’s why I am withholding belief until there is evidence. His approach to everything was to tolerate ambiguity until there’s evidence,” she clarified.

Sasha emphasised that this respect for ambiguity and evidence is why she chose to describe herself as secular in her book. “This means I don’t participate in the world of belief because the things I have evidence for fulfil me in those ways and because those ideas are worthy of celebration,” she said. “I don’t think it is for me to say anything on behalf of anyone else.”

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

COMMENTS (1)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ