History, revolution and revenge — Iran’s grand strategy

Despite geo-strategic constraints and economic hardships, Iran remains defiant, proud and extremely nationalistic

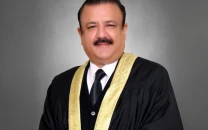

Iran President Hassan Rouhani. PHOTO: REUTERS/FILE

Iran to this day remains under the aura of its imperial greatness of the Achaemenid (6th Century BC to 330 BC), Sassanid (224 to 651 AD, destroyed by the Arabs) and Safavid rule (1501-1736 AD). Despite contemporary geo-strategic constraints and economic hardships, Iran remains defiant, proud and extremely nationalistic. Whether such sentiment — fostered by the 1979 Revolution and serving as the foundation of Iran’s agile foreign involvements and grand strategy — is defensible, is quite another debate. Historically, Iran has been considering large swaths of Central and South Asia and parts of the Arab Peninsula as its sphere of influence. The battle between the “uncouth” Arabs and the sophisticated “ajam or faaris” (Persia) continues to this day.

Middle Eastern map reveals Arabian Peninsula (Saudi Arabia), Anatolian Headland (Turkey), and Iranian Plateau (Iran) as three major geographic regions. These regions converge on Syria-Iraq territory, historically called the “Fertile Crescent” that has remained a contested space, therefore inherently unstable. All three — Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Iran — operate through a network of regional allies. Saudis lack the geopolitical tools to cover the entire Middle East. Turkey’s wider geopolitical ambitions to “reclaim” the ‘Turkish Middle East’ are in the works. Iran is the only power with clearly articulated strategic vision and ambitions, rooted in its history, geography and in the revolutionary zeal.

Historically, Iranian state has vied for a direct land access to the economically and militarily important, Mediterranean Sea. Gen Qasem Suleimani had strategised to extend Irani influence to the Mediterranean shores and succeeded, like the Sasanian Shah, Khusro II, who controlled eastern Mediterranean in 610s-620s AD. This explains Iran’s involvement with Lebanon’s Hezbollah; and in the politics of Syria, Lebanon and Iraq; and in establishing what is called a “Shia Crescent”.

Iran’s Grand Strategy, therefore, can be summed up as the “domination of its area of influence (up to and including Mediterranean) by championing the cause of Shia Islam and exporting its influence through a combination of hard and soft power comprising alliances, militant proxies and cultural encroachment”. Militant clients have remained the main pillar of Iran’s Grand Strategy since the Revolution. This approach has helped Iran against Western domination, enabling it to export its religio-political worldview, extending its military reach and power, reducing political costs of its foreign adventures and bolstering its regional allies and proxies.

However, projecting more influence from its Mediterranean springboard requires neutralising Israel, defeating Saudi Arabia and the GCC, nullifying Jordanian opposition, accommodating or challenging Turkey, avoiding infringing upon Russian interests, and most importantly forcing US/ Europe to abandon the region. This involves unbearable expense in blood and treasure. Consequently, Iran feels boxed-in by US pressure and its regional military footprint; unified regional adversaries; accidental and/ or unintended escalation with the US and other regional adversaries; and enduring instability and insecurity in the region.

Just like the US, as discussed last week, the Irani calculus also borders irrationality. Economic compression after prolonged sanctions is one major cause for such behaviour. In 2016, after one year of partial relief from sanctions (re-applied in 2018), Iran’s economy shrank by 3.9%. It is likely to shrink another 6% in 2020. Oil exports reduced by 50% and inflation rose from 9% in 2017 to 31% in 2018. The cost of food (bread, milk, vegetables and poultry) rose by 40 — 60%. Basic medical care and housing costs rose by 20%. The cumulative effect has been strikes and protests continuing to this day.

Iran also provocatively retaliates against US allies having an economic relationships with Iran to make them feel the pain, as evident from impounding British and Japanese sea vessels, besides attacks in the Gulf, Strait of Hormuz and on Saudi oil facilities in 2019. Ironically, the Iranian strategic paradox involves tying down US forces in the Gulf by opposition to Israel — Iran’s raison d’etre according to Khomeini’s ideology — and drawing Israeli forces in Lebanon and Gaza on the one hand, and working to evict the US from Iraq and Afghanistan on the other, as evident from the recent resolution passed by Iraqi parliament and Iran’s increased pressure on Afghan Taliban.

Tehran’s disastrous war with Iraq — causing more than a million casualties with over 300,000 fatalities and US $ 645 billion in treasure — has profoundly shaped Iran’s military thought. Consequently, Iran responds to regional challenges and opportunities through an “offensive and defensive strategy”, involving layered defence and asymmetric responses, to match its ambitious goals with limited resources and unanticipated situational demands. Its 1992 Military Doctrine draws upon atypical combination of conventional forces (emphasising ballistic-missile programmes), and the manipulation of geography and Revolutionary energy. Avoiding direct and extended conflict with superior powers, Iran prefers the use of unconventional forces and proxies instead, eschewing higher casualties.

Demonstrating unwelcome influence, Iran consolidated gains in Iraq by 2011 when Iran’s forces and political allies were fully entrenched. In Syria, initially dubbing its involvement to protect Syria’s Shia community and shrines, it has successfully reduced Bashar Al-Asad’s regime to a subservient client. In Yemen, Iran fully exploited the unexpected fall of Sanaa to Houthi rebels in 2014, seeing a chance to undermine Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and extending its influence towards Red Sea. Iran has advised Houthis, provided them funds, ballistic-missiles technology, UAVs (Unarmed Aerial Vehicles) and explosive-laden remote controlled boats, skewing the War against the Saudi Coalition. Iran deploys cyber capabilities effectively, providing cyber tools and training to Lebanese Hizbullah. The brinkmanship on show after the killing of Gen Qasem Suleimani fits well into the above strategic and doctrinal framework. Without condoning the killing which was unlawful, unprecedented and escalatory, Iran’s response was more bluster and less substance due to inbuilt restraint that allows simmering but no boiling over. Informing the US for retaliation through Switzerland, Iran adhered to US instructions for “proportionate revenge”, launching attacks on isolated parts of US bases in Iraq with minimal US casualties. Having seemingly placated domestic anger over the killing and having established the “perceptual equilibrium” with the US, Iran calmed down. Downing of Ukrainian airliner further diminished Iran’s revolutionary zest. This pattern is likely to continue due to Iranian animosity towards the US presence — in the region generally and Iraq particularly — and Washington’s moves to limit Iranian influence. The region should brace up for more rocket and missile attacks, assassinations and clandestine operations with escalatory rhetoric and ultimate buckling down.

Decision-makers in Iran would like to preserve their networks of patronage and proxies in Yemen, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and elsewhere, without getting into an open military clash with the US, which may prove fatal to the very foundation of Teheran’s vision and Grand Strategy. So far it is holding.

Published in The Express Tribune, January 23rd, 2020.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ