In the first quarter (Jul-Sept), the trade imbalance came down to $5.7 billion compared with $8.7 billion in the corresponding period of FY19, down a substantial 34.8%. Likewise, the current account deficit narrowed $2.7 billion or 64.3% year-on-year.

In FY19, the fall in trade deficit was exclusively on account of decrease in imports as exports remained stagnant. In FY20 (Jul-Sept) as well, imports declined 20.6% while exports registered only 2.7% growth.

If the first-quarter trend continues, FY20 is likely to end up with $23.6 billion in exports, $43.5 billion in imports and $20 billion in trade deficit. However, this is a very rough projection, because it is based on the unwarranted premise that key independent variables relating to both exports and imports will remain substantially the same.

For example, if the economic growth in major export markets, notably China and the United States, slows down, or in case the Chinese currency depreciates further, or world oil prices go up due to volatility in the Middle East, the overall trade deficit at the end of FY20 will be much higher.

It is, however, almost certain that the external deficit size on June 30, 2020 will in large part be a function of imports rather than exports. This is hardly surprising as stabilisation policies put brakes on economic growth and are thus inherently biased towards import compression rather than export expansion.

Paradoxically, however, the stabilisation policies may also end up increasing imports by reducing the domestic output. At any rate, Pakistan’s import-to-GDP ratio is 19% compared with the export-to-GDP ratio of 8%.

A popular view links the large import bill to the high propensity to buy foreign goods. Therefore, it is argued that if each Pakistani shuns foreign products and buys only locally made goods for at least three months, it will set the stage for putting the balance of payments position back on track.

Let’s assume this view is valid. There are two ways in which imports can be slashed. One, the government may restrict imports through administrative steps ranging from imposing high customs or regulatory duties to clamping outright prohibition on imports.

However, in view of the country’s commitments arising out of legally binding multilateral and bilateral international agreements, only a limited policy space is available to the government to scale down imports.

Restrictive measures may force the country’s trading partners to retaliate by subjecting its exports to a similar treatment. The result will be a zero-sum game.

Consumer needs

While the government may have its hands tied, the citizens are free to choose. No international agreement compels private individuals to prefer foreign over domestically produced goods.

But then why do people spend billions of dollars on foreign goods each year? The answer is that buying foreign or local products is largely a question of consumer needs and wants.

Imports represent the difference between domestic demand and domestic output (minus exports). The wider the gap, the higher is the import volume. All else equal, high imports are undergirded by low or inefficient productivity.

Pakistan is among those countries which have a very narrow production or manufacturing base. We are essentially a producer of primary products such as wheat, cotton, sugarcane and rice, and low value-added manufactures such as textile, sugar and leather articles, which are derived from these primary products.

A wide range of products that the country’s households, businesses and factories consume are either not manufactured locally at all or are produced in relatively small quantities or on a low quality scale. Such products include oil and gas, chemicals and fertilisers, pharmaceuticals, iron and steel, machinery and electronic equipment, vehicles, consumer durables and aircraft. In case we don’t import these products, our factories will be forced to shut down and households will be deprived of a decent living.

Domestic supply-side constraints are well brought out by the net imports (difference between exports and imports). Pakistan is an agro-based economy but still it is a net food-importing country to the tune of $1.1 billion annually.

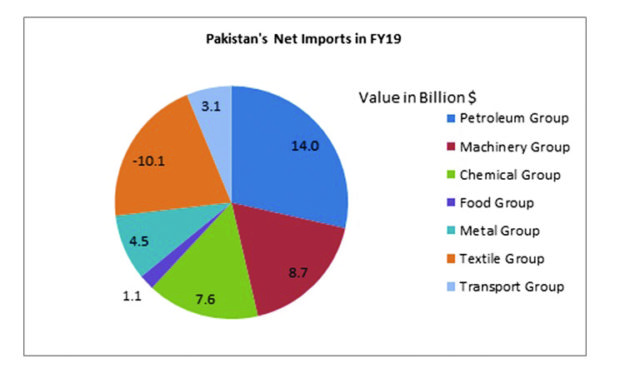

Rice is the only crop which is consistently produced in surplus. Net imports in case of other product groups in FY19 were as follows: petroleum group ($14 billion), machinery ($8.7 billion), chemicals and pharmaceuticals ($7.6 billion), metals ($4.5 billion) and transport group ($3.1 billion).

The only product group in which we have net exports is textile ($10 billion). However, despite being the world’s fourth largest cotton producer, Pakistan imports cotton as the local produce is not deemed of export quality.

Since the performance of the entire textile value chain depends in large measure on cotton quality, the exporting enterprises prefer to use imported cotton. In FY19, $936 million worth of cotton was imported.

Not only that, over the years cotton output has declined because of shrinking area on which the crop is cultivated. In FY19, only 9.9 million bales of cotton were produced compared with 11.9 million bales in FY18 as area under cultivation shrank from 2.7 million hectares to 2.4 million hectares.

Even in industries where we have sufficient productive capacity, the efficiency of the production process and the quality of products are below the mark.

Utility maximisation

Customers, whether they are households buying for consumption or industrial users purchasing for producing goods and services, want the best value for their hard-earned money. While making purchase decisions, they are guided by the utility maximisation rule, that is to say, within their budget constraints, they will buy that basket of goods and services which, they believe, gives them the highest possible satisfaction.

While satisfaction is subjective and consumers may look for different product characteristics in terms of colour, taste, size, weight and texture, consumer behaviour is not all that arbitrary.

While shopping, the customers have some expectations from the manufacturers or suppliers in terms of product reliability, performance, safety, conformity to standards and after-sales service. No one expects their new refrigerator, no matter of which brand, to go kaput when the mercury rises.

When fulfilled, the expectations create brand loyalty. The principal reason for preference for foreign brands is that there are few local brands which command customer loyalty. Of the food items that Pakistan imported in FY19, palm oil had the largest share ($1.84 billion) followed by tea ($572 million) and pulses ($506 million). The consumption of tea and pulses is part of our culture and it is difficult to significantly bring down their imports.

As for palm oil, its import reflects preference for processed fruit, which uses it as an ingredient. Pakistan does not produce palm oil while only a limited amount of tea crop is grown in the country. Likewise, pulses are cultivated on less than 5% of the crop area.

Together with rice, they constitute the staple food for the low-income households. Thus, it is only by shoring up the productive capacity of the economy and developing credible local brands that dependence on foreign products can be shed.

The writer is an Islamabad-based columnist

Published in The Express Tribune, November 18th, 2019.

Like Business on Facebook, follow @TribuneBiz on Twitter to stay informed and join in the conversation.

1732003896-0/Zendaya-(1)1732003896-0-165x106.webp)

1731914690-0/trump-(26)1731914690-0-165x106.webp)

1732003946-0/BeFunky-collage-(70)1732003946-0-165x106.webp)

1731749026-0/Copy-of-Untitled-(3)1731749026-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ