Spooky action at a distance

The Express Tribune speaks to best-selling author Philip Ball about the inherent weirdness of quantum theory

PHOTO COURTESY: MEDIUM

Long before humanity devised the experiments to test the postulates of the 20th-century scientific theory, writers and poets had picked up on the idea of quantum entanglement, popularising the delightfully bizarre concept through romantic analogies.

Basically, entanglement happens when two particles come together, vibrate in unison, and are separated. However, quantum theory predicts that the particles, once they have interacted, somehow remain linked to each other, despite being physically apart.

Rekindling the light snuffed out by patriarchal honour

This mysterious connection, for which an intuitive explanation is hard to find, can be over any distance, even if that distance is an ocean of space, a whole universe, or even more. Entanglement happens instantaneously and should obey the laws of physics, like every other occurrence.

The proposition has philosophical implications. Entanglement has led to the realisation that before time had begun as humans know it today, when the universe was still a soup of basic particles, interacting and moving in unison, there was a strange force connecting everything together – since logic dictates that every particle has a common origin.

However, new research in the field has debunked many of the old claims about entanglement, dismissing them as mere interpretations piled on top of the quantum theory. A new term, referred to as quantum non-locality, allows for influence to propagate across space-time, without letting observers manipulate it, neatly fitting into the quantum and classical universe.

The fable of the other Nobel laureate from Pakistan

In a new book which aims to explain this entanglement, as well as quantum mechanics, one of the most difficult and obscure subjects in all of science, author Philip Ball has tried to give words to the complex mathematical equations of the theory.

However, actual math barely makes an appearance in the book, which can be interpreted as an attempt by the author to cater to a wider audience.

Philip Ball is a British science writer who has contributed to reputable publications such as Nature, The New York Times, The Guardian, and New Statesman, among many others. He has also worked on popular shows about science on television and radio in the United Kingdom.

Although Ball has authored many books over his long career in the media, some of his most famous works include 'Critical mass: How one thing leads to another', published in 2004, and 'The Music Instinct' which came out in 2011. Ball is different from other authors in that he boasts a body of work which is intriguing and incredibly broad.

The (dis)order of time in the words of a poetic physicist

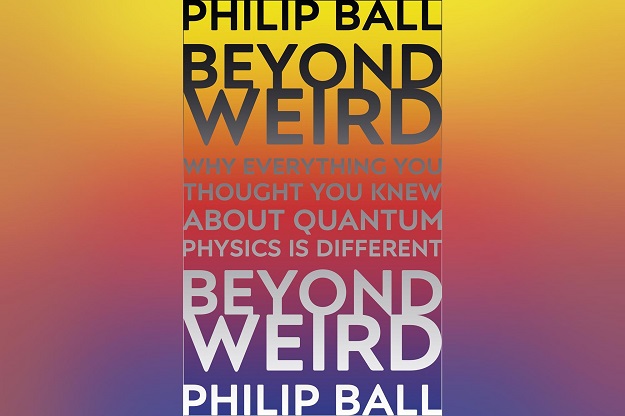

'Beyond Weird: Why everything you thought you knew about quantum physics is different' was published by Penguins Books, United Kingdom, on December 18, 2018. An audiobook, narrated by British actor Jonathan Cowley, also accompanied the release of the print version.

According to Ball, the quantum world is not a different world, but our world, and if anything deserves to be called ‘weird’, it is the grasp our species has on the laws of nature. The exhilarating book, in the words of the author, talks about what quantum math really means – and what it does not mean.

The Express Tribune spoke to author Philip Ball about the science, quantum physics and the inherent weirdness of some scientific theories. Parts of the conversation with the celebrated author have been reproduced below for interested readers. A short review of 'Beyond Weird' follows the conversation.

CREATIVE: IBRAHIM YAHYA

CREATIVE: IBRAHIM YAHYAIn conversation with Philip Ball

Author Philip Ball. PHOTO COURTESY: PHILIP BALL

Author Philip Ball. PHOTO COURTESY: PHILIP BALLIs humanity any nearer to a grand understanding of the universe?

We are always getting nearer, slowly. But the more we know, the more we discover how much we don’t know – for example, about dark matter, dark energy, how genomes work … Simply finding better and more questions is progress, though.

In the book, you point out that it is not quantum mechanics that is weird, but our understanding of it. Can the same argument not be made for other scientific theories out there?

I don’t quite mean to put it that way. Quantum mechanics seems strange to us because the way its rules play out at the scale of humans – much, much bigger than atoms – “disguises” them and makes them look like a different sort of physics (i.e. classical). What I argue against is the tendency to call quantum mechanics “weird” as if it was a different kind of physics altogether, distinct from what we experience.

This seems to simply inhibit our readiness to engage with its message. We now have a pretty good, even if not complete, understanding of how quantum physics gives rise to classical physics – there’s no divide between the everyday/intuitive and the “weird”.

All the same, quantum mechanics is a very unusual kind of theory because it seems to speak only to our experience of the world – it tells us what we will observe – rather than to “what is really happening”. It forces us to make only indirect inferences about “what is really happening” – and no one is yet agreed on the answer to that!

The book reads like an attempt to make sense of the results of quantum experiments from a philosophical perspective. How hard is it to reconcile philosophy with quantum mechanics?

The question of what quantum mechanics tells us about the “nature of the world” is profoundly philosophical – I would say that quantum mechanics is a place where physics and philosophy are compelled to meet and enter into dialogue, which is a good thing. (And which refutes the shallow claims of some physicists that philosophy is “dead” or useless.)

There are philosophical questions about quantum mechanics that might one day be resolved or at least clarified by experiment – but we can’t be sure that the foundations of quantum mechanics can ever be partly a matter for philosophy.

Certainly, there are deep philosophical implications, and it would be good if more physicists become careful about bandying words like “reality” which philosophers have thought about profoundly for millennia.

How important is understanding quantum physics for the future of our species?

In one sense, not very! We can and will make progress in science and technology without a deeper understanding of quantum mechanics.

But one of the most striking aspects for me is that some of the quantum information technologies that are emerging and which might have a big impact on society – such as quantum computing and quantum cryptography – are not simply “applied quantum physics”, but are intimately tied up with foundational questions.

Indeed, some of these foundational questions are now being framed in the language of “quantum information” – and I think this is a productive way to go.

How would you describe your experience of writing a book on a complex topic for a mass audience?

It’s a huge but enjoyable challenge! That’s true for any complex topic (not just in science). But writing on quantum mechanics is especially challenging because it involves talking about things for which we really have no adequate language: our language is designed for the classical world.

When you can’t even use the word “is” with confidence, you have to work particularly hard! And I was intentionally making life difficult for myself here because I wanted to show why many of the conventional ways quantum mechanics is popularised are misleading and miss the point, as they attempt to “translate” quantum phenomena into classical pictures – which is precisely the wrong way to do it, though it’s hard to see how else one can give readers a handle on the subject.

My aim, as it is with all my writing on science, is to avoid using neat-sounding but ultimately simplistic slogans, and to trust the reader’s intelligence without assuming any specialist knowledge.

Can you tell us a little bit about your future projects?

My next book, to be published in the UK at the end of May, stems from a project I was involved in recently in which a small piece of my flesh was removed from my arm and transformed in the laboratory into a kind of rudimentary miniature brain.

The book is about this technology of “cell reprogramming”, which shows that at least in principle any bit of us can probably be transformed into any other bit of us – skin into neurons, say, or into sperm or egg cells.

The book looks at what these discoveries and technologies imply not just for future medicine but for our sense of self and identity. It is called 'How To Grow a Human'.

Do you have any message for young physicists reading The Express Tribune?

Don’t be misled by claims of a “crisis in physics”, which are really about how some parts of high-energy physics are challenged by the inability of experiments to test speculative theories such as string theory.

That is only a tiny part of physics, which as a discipline is thriving.

At the same time, there are massive holes in our understanding of the physical universe, such as what dark matter and dark energy are, and how to reconcile quantum mechanics with general relativity, and how quantum phenomena such as entanglement might lie at the heart of what actually is space-time.

These are marvelous opportunities, and make physics a good subject to enter.

Don’t, however, just study physics. Knowing more about chemistry, biology, the history and philosophy of science, as about the humanities in general, will only enrich your work in and appreciation of your chosen subject.

A visual representation of Schrodinger and the cat, a famous thought experiment. PHOTO COURTESY: NEW STATESMAN

A visual representation of Schrodinger and the cat, a famous thought experiment. PHOTO COURTESY: NEW STATESMANBeyond weird

PHOTO COURTESY: CHEMISTRY WORLD

PHOTO COURTESY: CHEMISTRY WORLDIn the book, Philip Ball has tried to put forth the argument that it is not the quantum theory that is weird and puzzling, but perhaps our understanding of it. The author writes that the theory merely reveals the inner workings of nature, and human beings, living as they do in a 'classical world', have difficulty grasping it in its entirety.

Ball also separates fact from fiction, educating readers about the concepts that are not a part of quantum theory, but have become synonymous with it, and are responsible for propagating misunderstandings about the theory. They are presented as a list, along with accompanying explanations, for easy consumption.

In addition, the British writer makes the case that although humanity still has a long way to go before it can fully grasp quantum laws, it is pertinent to mention that the species has framed significantly better questions to make sense of it, which is encouraging.

Tribune Take: reading habits of Pakistanis on print and digital

Some of the new developments have to do with experiments that scientists can now conduct to test quantum postulates, including the famous thought experiment known as Schrodinger's cat. These experiments have in part been made possible by drastic improvements to laser technology, mirrors, and lenses.

Ball also discusses the emergence of quantum technologies, and how these have changed previously-held conceptions about the field. Scientists no longer think of quantum laws as weird, but actively seek to decode the challenge with new perspectives.

However, the author admits that there is still a long way to go before humans can devise analogies which can explain quantum paradoxes without limiting or exaggerating the reality.

A pact with the unsettling nature of the theory might be the most apt way of tackling quantum physics, argues Ball.

The incredible story of the man who raised Malala

"It might be, then, that all we can ever do is shut up and calculate, and dismiss the rest as a matter of taste. But I think we can do better and that we should at least aspire to. Perhaps quantum mechanics pushes us to the limits of what we can know and comprehend. Well then, let’s see if we can push back a little," the author urges readers.

'Beyond Weird' won the Physics World Book Prize of 2018, and there is good reason for it. Ball has penned a unique and readable work on quantum theory in elegant and simple language. If nothing else, the book will push readers to test the limits of their apprehension, acquainting them with methods to appreciate the mysterious workings of nature.

Almost nine decades after Albert Einstein, perhaps the most famous physicist of all time, called quantum theory incomplete and dismissed entanglement as spooky action at a distance, humanity is beginning to appreciate the true meaning of the strange term.

Writers and poets are picking up their pens again and making them dance to the tune of particles which make up the fabric of being, connecting each and every one of us across space and time.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ