The fable of the other Nobel laureate from Pakistan

Pureland author Zarrar Said talks exclusively to The Express Tribune about new book, society and value of fiction

PHOTO: ONLINE

Although it is very important to read non-fiction, giving time to fictitious undertakings is not entirely useless. Fiction helps in understanding different perspectives, deepens understanding of the human character, and allows one to see the big picture.

In Pakistan, writers are few and far between. A country full of poets and philosophers, good fiction writing is hard to come by. A young author is striving hard to correct this imbalance. 38-year-old Zarrar Said recently wrote a book called Pureland which has received encouraging reviews from many critics.

Pureland was released by Harper Collins Publishers in November 2018. The New York-based author attended an event related to the book at Lahore Literary Festival last week, where he talked extensively about the value of fiction and creative writing.

Facsimile editions of ancient manuscripts fight digital blitz

The book tells the story of a young boy from a small village in central Punjab who stuns the world of science with his genius and wins the Nobel prize in physics while abroad. The author says the book is his first attempt at writing fiction.

"I piggy-backed off the research friends of mine did related to a documentary on the life of Abdus Salam. But I realised the story was so fascinating that it would make much more sense to write it as a fictitious novel," Said told The Express Tribune.

“Cultures will suffer from the prejudices that they keep. One example is Germany losing Einstein to antisemitism. MF Hussain spent the last years of his life in exile because Hindu fundamentalists wanted to slay him. In the same way, Pakistan lost out on Abdus Salam’s achievements," he added.

Delve into pre-Islamic Arab poetry in modern English

Pureland has been pulled off the shelves in some parts of the country due to the backlash it has received from certain parts of the society. Perhaps publishers are just being extra-cautious about the safety of their bookstores, but the fact remains that the publicity has only added to the appeal of the story.

The author is still hopeful about stores in Pakistan taking back their decision. Indeed, he says that some of the meetings that he has had with bookstore owners have gone positively. The frustrating part about the whole controversy is that nobody seems able to give Said a reason for not promoting the book.

The Express Tribune spoke to Zarrar Said about his work, the importance of fiction, and the story of Abdus Salam. Parts of the conversation with the author have been reproduced below in their entirety for interested readers. A short review of Pureland follows this interview.

Orient meets Occident as Louvre Abu Dhabi rains light on art

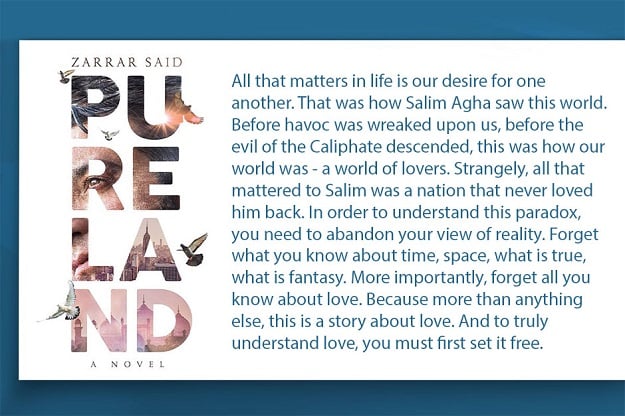

An excerpt from Pureland. CREATIVE: IBRAHIM YAHYA

An excerpt from Pureland. CREATIVE: IBRAHIM YAHYAIn conversation with Zarrar Said

What is the story behind the story of your main character?

Twenty years ago, when I went to college, I was a physics major. I came across the story of Dr Abdus Salam, a boy born in a village who goes on to change the world of science wins the Nobel prize in physics and is excommunicated from his country.

I found this to be a very profoundly human story, and I wanted to write about that for a very long time.

Pureland is an intriguing title for a book that is actually about love of a very different kind. Why highlight one romance over the other in the title?

I think the notion of a homeland is also a very strong love story, and I think in the book there is a comparison of Adam and Eve and the garden of Eden.

So, the story is not complete. Adam and Eve is not complete without the element of the garden.

In the book, you constantly play with reality and fantasy, and it is sometimes difficult to separate the two. What purpose do these other-worldly encounters play in your tale?

The very nature of the story had to be told in direct relationship with fantasy and reality. There is multiple ways of telling the story.

I thought this was the most appropriate way to do it because the actual story itself is pretty magical. Hence, the magical realism. I did not even know what it was that I was doing until much later.

How have your personal experiences as a physics major shaped your interest in the life of Abdus Salam?

It was very instrumental. Abdus Salam is a very instrumental figure in any physics major's or any science major's life. It is kind of like learning about Michael Jordan when you first pick up a basketball.

So this is a story that has been told in the world of science over and over again. For me, I find it really sad I had to leave the country of my birth to learn about it.

A mentor of mine used to say that fiction often serves as a potent tool to humanise great tragedies. How differently do you think people would have reacted to a simple biography of the great scientist?

It would have been a lousy book, to be honest. If I did a non-fiction version, it just would not have worked.

I tried it, and it did not work, and I had to go back and retell the story the way I think it should be told.

In the book, the main character often gives voice to long messages of, what some would say, a political nature. Who are these for? Why are they so important?

It was not done intentionally, the political messages. But I think you cannot talk about a lost homeland, and you cannot talk about hatred and things like that which go into a systematic, dysfunctional society.

It has to be told in this way, there is no other way to do it. You cannot take politics out of it. I tried it, and it just did not work. I think it was very important to lay the groundwork for where you are. The landscape of where you are.

In order to do that, you have to talk about the politics. And I think also, my editors pointed that out to me that I had to put that in there. It wasn't there originally.

Certain parts of the tale seem borrowed from real-life incidents, and the story of Salam merges with Salman Rushdie at one point. How much of the book is meant for the consumption for a young Muslim, as opposed to a young Muslim from the land of the pure?

You know, I did not write the book with just one audience in mind, so I think the book is meant for everyone.

And I think even the message in the story is that Pureland can be anywhere, and that is the beauty of fiction, that it can be relatable to people from all walks of life.

The nicknames are perhaps the most amusing part of the book. You have to tell us how you conjured these up?

I worked really hard with names. I think I was inspired by PG Woodhouse, who used to come up with phenomenal names for his characters.

These names, if you concentrate on why they are there when they are there, you will understand that it is not just randomly thrown in there. So there is reasons behind why people are called certain things.

Can you tell us a little bit about your future projects?

I am doing a young adult novel. I have actually done it and I am looking forward to pitching that with my agent here in New York.

Do you have any message for young writers who are reading The Express Tribune?

I just think that the only advice I would give to writers is that do not be a writer and a critic at the same time. When you are exercising your creative muscles, you cannot restrict them by becoming an editor at the same time.

Give yourself the freedom to write whatever you have to. Let the subconscious take over and it will do all the work for you.

CREATIVE: IBRAHIM YAHYA

CREATIVE: IBRAHIM YAHYABook review

Pureland is the story of a poor boy from a village near Lahore who benefits from the generosity of the local feudal lord and goes on to become one of the greatest scientists the world has ever seen. Narrated by a notorious character nicknamed Scimitar, the assassin of an outfit called The Caliphate, the book details the tragedies and triumphs of Salim Agha from his birth in Khanpur to his death in exile in the United States.

Roughly divided into three parts, the first of which pours over the amusing details of life in dirt-poor Khanpur, followed by the stark contrast of elite living at a feudal house in Lahore, and ends with the madness of cosmopolitan New York. The author has a flair for conjuring up interesting characters that are funny and relatable, although the novel also dives into the magical realm, trying to link the terrestrial dynamics of life in this world to the celestial mysteries of the cosmos.

Set in a fictional country called Pureland, an obvious reference to the land of the pure (Pakistan), the narrative often gives way to long dialogues of a political and social nature, mostly mouthed by the Scimitar. These serve to portray the real message of the book, which was originally conceived as a simple biography of Abdus Salam (the first Nobel laureate from Pakistan), and how heroes define a people and their ethos. Silence in times of turmoil comes at a terrible cost, according to the feared assassin.

The incredible story of the man who raised Malala

The author seems intimately familiar with life in Pakistan, and the characters and their conversations with each other are evidence for his deep knowledge about the sub-continent in general. Although the writings of other Pakistani authors like Mohammed Hanif and Fatima Bhutto on radicalism this year seem a little confused and cliched, perhaps because they were written for western audiences, Zarrar Said comes across as unapologetic and refreshingly fierce in his work. Pureland is perhaps the best novel from a Pakistani author this winter and deserves recognition of some sort.

Said begins each different part of the book with a quote from the writings of a famous author describing the contents of the pages to follow. The quotes are powerful and chilling. For example, just before Salim Agha is forced abroad for higher education, Said narrates the saying of his Palestinian namesake, famous for writings on Orientalism, wherein the latter notes that the achievements of exile are permanently undermined by the loss of something left behind forever. The poetry of Urdu giant Mirza Ghalib also makes an appearance along these lines, connecting the modern to the ancient.

Said says he has worked very hard on the nicknames given to some characters in the story. The dwellers of Khanpur, where the small village is the only home people ever know, and where they live their whole lives oblivious to the world around them, are the most interesting. There is Tamboo the Camel, Billa Cycle, Wannu the Weasel, Khassi Kasai, Cut-Two Nai and Pappu Pipewalla, among countless others. In the small town, the names often provide a defining personality trait, and have a story behind them.

Absurdities of contemporary warfare collide as satirical thriller bites literati

The inhabitants of Khan House in Lahore, the feudal-general benefactor of Salim Agha, are also from this village, although most have left the life of Khanpur behind them. The contrast provided by the life of luxury in this house, compared to the village, is very relevant to the inequalities inherent in our society. Inspired by the story of Salam, a Nobel winner for pioneering work in physics, the main character of the book does not see a light bulb until he is fourteen-years-old, a rather remarkable occurrence.

The life of Salim Agha in New York has not been dwelt upon much by the author, who chooses to focus on the nostalgia for the homeland that a life in exile brings with itself. Throughout the parts of the book which are set outside Pureland, one is constantly reminded of life back in the country, and how it clashes with the values of a big city. Salim Agha longs to return to the place where he fell in love, with books, with physics, with life, and, with a girl.

Towards the end, there are multiple twists to the story, almost Bollywood-esque. However, even these fail to take the spotlight off the otherwise brilliant plot and the writing which compliments it. A beautiful and powerful book, Pureland is a must-read for even the most skeptical of readers, who will come away from it feeling a profound sense of loss over the love and life of Abdus Salam.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ