Heartland politics: Pir power in Punjab

Around 16% members of last National Assembly belonged to ‘spiritual’ families

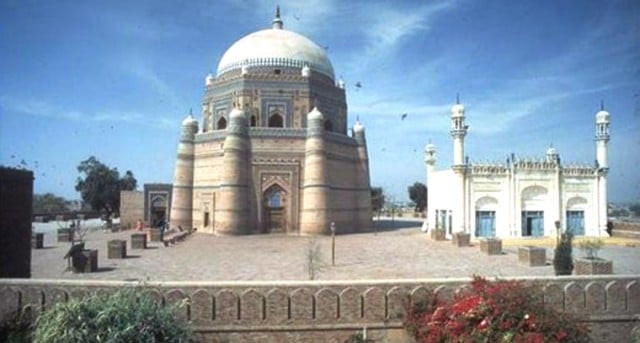

Thousands visiting Multan’s famous shrines now fear for their safety in these sacred places that were meant to provide ‘a safe haven’ for all who came there. FILE PHOTO

The political power of shrines is anchored in Punjab’s colonial history that placed pirs in a favourable position, allowing them to combine their religious authority with landed power.

Supported by systematic colonial patronage, shrine elite made an early entry into the politics of pre-partition Punjab. The pir-zamindar equation has ever since been very much relevant and is an important component in rural politics of the province, particularly South Punjab.

Historically, pirs have been courted by every ruler in Punjab. When the British rulers started consolidating their control over Punjab in the nineteenth century, they accosted shrine elite and other notables of the time for support.

Pir Pagara calls political parties to unite

Historians claim that support of shrine families was critical in crushing 1857 uprising of local people against the East India Company. Many shrine guardians issued religious decrees (fatwas) that dissuaded their followers from taking up arms against the British and some others provided men and material support to quell the abortive war of independence.

Fidelity offered by pirs to the British was rewarded through land grants, honours and official positions. Members of selected shrine families were appointed ‘zaildars’ in the colonial era. Many leading shrine families also benefited from the Court of Wards – an instrument of the time that prevented elite fragmentation if family head died or got under deep debt burden.

The most significant legal intervention that protected the landed interest of shrine families was the introduction of the Land Alienation Act of 1900. The law barred the sale of land to non-agrarian casts. This act embedded the nexus between religious and landed class in Punjab, which continues to persist even today.

Traditionally, when shrine guardians throw their weight behind any power proposition, the very legitimacy of their spiritual lineage and shrine brotherhood is invoked.

Deference to established norms is a fundamental component of the religious eco-system of shrines. More superstitious believe that a violation of shrine norms or disobedience to a pir will invite evils or activate supernatural forces against them and their families.

According to a research by Dr Adeel Malik, a professor of development economics in Oxford University, there are around 64 shrines in Punjab with direct political connections. In around 42 tehsils of the province, there is at least one politically influential shrine. Multan has the highest number of shrine families in politics, followed by Jhang, Khanewal, Rahimyar Khan, Taunsa Shareef, Khairpur Tamewali, Chishtian and Okara.

This research says 19 per cent of the total rural Muslim constituencies in 1920 and 1946 provincial assembly elections were occupied by the shrine families. The ration is still intact. Around 16 per cent of the total National Assembly members belonged to shrine families in the last assembly that completed its five-year term in May this year.

Pirs have always demonstrated a remarkable capacity to adapt themselves to the changing political realities. When British rulers permitted restricted enfranchisement in the 1920s, the shrine guardians who had already emerged as leading beneficiaries of colonial patronage were well-positioned to enter the political arena. Punjab’s prominent pirs got elected on rural Muhammadan and landed gentry seats.

Besides their traditional strongholds in south Punjab, several shrine families from central Punjab also participated in 1937 and 1946 elections and emerged as a formidable force.

In the early twentieth century, Punjab’s prominent shrine families aligned themselves with Unionist Party – an alliance of secular landed aristocracy of Punjab. When demand for Pakistan gained momentum, many of them joined the Muslim League. After independence pirs retained a permanent presence in politics and were well represented in all military and civilian dispensations.

When the Muslim League broke away into several factions after independence, pirs became part of new dispensations, including the Republican Party, formed in 1955.

When General Ayub Khan imposed martial law, Punjab’s leading shrine custodians joined him with great alacrity. Many of them later joined Conventional Muslim League, the King’s party till general’s grip on power weakened. They joined Council Muslim League and Qayum group immediately.

The first major political challenge to shrine families came with the rise of Zulifqar Ali Bhutto’s Pakistan People Party (PPP). It wiped out pirs from Punjab in 1970 elections.

But, this change was short-lived as the PPP opened itself to pir and fielded many of them in 1977 elections. The same shrine families did not wait long and jumped into General Ziaul Haq’s ship when he imposed martial law. They contested non-party elections and joined his majlis-e-shura with fervour.

By the time of Zia’s exit in 1988, shrine families were well-represented in the two major political parties – the PPP and the PML-N. A decade later many of them crossed over to the PML-Q, the party formed by General Pervez Musharraf who had come to power in 1999 by imposing third martial law in the country.

Now they have a sizeable presence in all mainstream parties including PTI, PML-N and PPP.

Not only do shrines families repeatedly switch political parties, members of the same family, at any one point in time are often associated with different outfits. Such simultaneous representation in different parties provides resilience against possible political shocks, and a means for political diversification.

In several rural constituencies of South Punjab, the pir and Makhdooms enjoy such loyal followers that they often manage to win without explicit party affiliation. Winning elections as independent candidates gives them the opportunity to join the party platform of their choice in the parliament.

For the 2018 elections, many shrine families are contesting from south Punjab.

In Multan, there has always been a close contest between shrine elite, the stalwarts of mainstream political parties. Gilanis, Qureshis and Gardezis are few such families.

They enter the election race forming local alliances against each other in local body and national elections. However, the contest remains between Shrines and their custodians.

In Multan among the decedents of shrine elite, Javed Hashmi, Shah Mehmood Qureshi and Yousaf Raza Gilani have always been vying against each other in local government, provincial and national elections since decades.

Even when former prime minister Yousaf Raza Gilani and Shah Mehmood Qureshi were in the same political party, the PPP, the relentless competition between them led Qureshi leaving the party on the issue of a change in ministerial portfolio.

Similarly, when Javed Hashmi was a federal minister in 1990s, in Nawaz Sharif’s cabinet he used his official status to claim custodianship of Bahauddin Zakaria Shrine, the ancestors of Shah Mahmood Qureshi.

Both Qureshi and Hashmi belong to Makhdoom Rasheed constituency and they have contested many elections against each other. Hashmi has withdrawn from election race this time.

Sikandar Bosan, a former federal minister and influential landlord who defeated the Gilanis in the last elections, had joined the PTI when dozens of other electable joined Imran Khan’s party in recent weeks.

Jahangir Tareen had played a key role in his joining the PTI, which initially awarded him a ticket but later withdrew it in favour of Ahmed Hasan Dehar, a former PPP MPA but now a close associate of Qureshi. Reportedly, Qureshi was instrumental in denying this ticket as his group did not want to lose its hold in the area.

This month’s electoral race will be interesting in Multan as after many decades it will be a direct contest between Gilani and Qureshi. In neighbouring Khanewal district, a cousin of Shah Mehmood Qureshi, Pir Zahoor Hussain Qureshi, is a PTI candidate from NA-152. His opponent, the PML-N candidate Pir Aslam Bodla, is trying to garner the support of Gilani pirs of Multan.

Pir Sialvi agrees to call off protest after meeting Shehbaz

In Rahimyar Khan district, Makhdoom Khursu Bakhtiar along with many other South Punjab politicians deserted the PML-N and formed South Punjab Mahaz which later merged with the PTI, Bakhtiar will be contesting against the PPP’s Makhddom Shahab Uddin. The two are cousins and belong to Mianwali Qureshian shrine.

Custodians of Sultan Bahu Shrine are contesting elections on the PTI tickets at the NA-114 and NA-116 constituencies of Jhang and will now be contesting against custodians of Shah Jewana Shrine. Custodians of Shah Jewana, Faisal Saleh Hayat and Syeda Abida Hussain had always been contesting against each other, but this time they are supporting each other against another shrine of Sultan Bahu.

Taunsa Shareef, a subdivision of Dera Ghazi Khan, is known for the shrine of revered saint Hazrat Muhammad Suleman Shah Taunsvi. Khawaja Attaullah Taunsvi, the custodian of the shire, was awarded ticket by the PPP. However, he declined the ticket and is contesting as an independent with a jeep symbol. He is considered favourite amongst the independents.

His cousin, Khawaja Sheeraz, is contesting against him on the PTI ticket. Sheeraz had contested last elections on the PPP ticket. Another pir, Hamid Saeed Kazmi, a former federal minister wanted to contest from Rahimyar Khan where he has more followers but his party, the PPP, offered him a ticket from Multan. He declined the ticket and is contesting as an independent.

Depending on where they are located and the strength of their network, pirs have bargaining power in the political arena. In regions where pirs are not in advantageous positions, they are engaged in negotiations and concessions.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ