Are we serious about exploiting human capital?

World Bank president Jim Yon Kim called on countries to invest in human capital, particularly in health and education

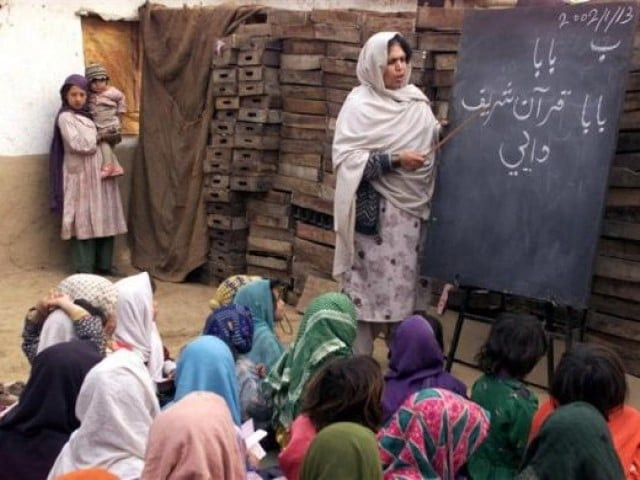

While the demand for primary education is now fairly universal, a large mass of children is out of school. PHOTO: REUTERS

Human capital development in Pakistan

Rather than at least going through the motions of giving a fair chance to all Pakistanis to reach their full human potential, it is easy for our politicians to throw out baseless slogans in the election run-up like “One government job for each family”, “10 million jobs in one year,” and “Jobs for all youth.” However well intentioned, such statements are not based on any grasp of the millions of jobs required each year or the challenges entailed. Indeed, the pilots have no map! If election campaigns were truly based on a proactive approach, informed by data and trends evident from reputed surveys and census indicators around human capital formation, education, labour force participation, and gender, the following priorities would be emphasised as emergencies:

1) Expedite a fertility decline by enabling the millions of Pakistani couples who want fewer children with quality family planning services. Since 2000, there has been hardly any change in Pakistan’s fertility or population growth trajectory. We now stand out as one of the few countries in the region to have a total fertility rate (TFR) of 3.8 births per woman. The slow fertility decline is doubly perplexing because of the strong changes in fertility intentions among Pakistani men and women, who want fewer children — the desired average number of births is one child less at 2.8! Data shows that there are 6.2 million women with unmet need for contraception, who undergo unplanned and unwanted pregnancies each year. Preventing such pregnancies and reducing fertility and population growth will lead to a range of health, nutrition, social benefits, as well as economic gains through a reduction in dependency. A faster decline is possible with the provision and expansion of quality fertility services to this large bulk of the population.

2) Achieve universal primary education (UPE) on an emergency footing. Achieving UPE is essential for any country to claim that it has invested in each of its citizens. While progress has improved somewhat, at our current slow pace, it will take us exactly 50 years to reach UPE in Pakistan. While the demand for primary education is now fairly universal, a large mass of children is out of school. As with fertility decline, this has become more of a supply-side issue which is largely responsible for the low enrollment rates distinguishing Pakistan from neighboring countries like Bangladesh and Nepal that are much closer to achieving UPE. A ray of hope is that girls aged 10–15 are showing rapidly increasing primary completion trends although they still lag behind boys. An education emergency or a crash programme is required whereby the Government of Pakistan accelerates efforts to achieve UPE by 2025–2030. UPE is the very base on which Pakistan will build its human capital for the next few decades.

3) Provide the right mix of education and skills to create a productive labour force. There is a need to carefully and urgently utilise the labour force potential available and provide employment opportunities internally and abroad. When many working-age adults cannot find employment or are underemployed, very well-known adverse social, economic, and even political consequences are likely to result. But if the working-age population is to be employed productively, it must have some basic education and skills commensurate with available employment opportunities. According to Population Council estimates, 40% of the labour force aged 15-64 (more women than men) have never attended school. And of greater concern, 4.4 million (27%) out of the 16.7 million young Pakistani men and women aged 15-24 entering the labour force are illiterate or uneducated. If we are to harness the productive potential of our labour force, relevant sectors must work together, on an urgent footing, to develop marketable skills.

1,261 children out of school in the capital

4) Open up opportunities for women and girls to participate in the labour force. Economic growth and poverty alleviation cannot be achieved if half the population, females, remain out of the labour force. Female labour force participation rates in Pakistan are one of the lowest in the region and have been stagnant for several years but are finally showing an increasing trend. Recent Population Council research reveals the less-known fact that large numbers of women and girls do want to contribute economically, especially as they get more educated and as they are freed from frequent childbearing. Most working-age women do not seek employment because of what they term personal or family responsibilities. However, recent Labour Force Surveys show greater employment among women at the two ends of the education spectrum, ie, those least and most educated. Those with no education have little choice but to break the barrier and accept menial work, out of necessity and largely due to lack of skills. And at the other end, educated women with degrees are able to compete more equally with men. We have to focus efforts to raise the opportunities for women in the middle group with some education, for example, through engaging with employers to offer women-friendly workplaces. This would immediately boost the current female labour force participation rate by reducing the obstacles women and girls face in coming out of their homes and going to work.

Admittedly it will be difficult to invest in human capital on the scale our population demands. But through a clear and integrated focus on the essentials, ie, (1) fast and substantial reduction in fertility (2) rapid achievement of UPE (3) careful cultivation of productive skills and (4) facilitation of women’s economic participation — all of which we know to be aligned with the aspirations of the men, women, youth, and children of Pakistan — we can at last begin to harvest our demographic dividend and truly capitalise on the vast potential of our resilient nation.

Published in The Express Tribune, July 1st, 2018.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ