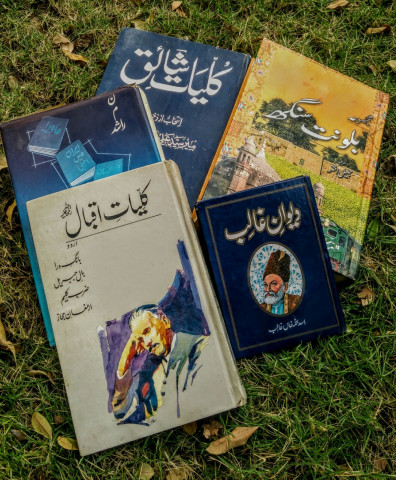

The ‘Kulliat’ phenomenon

Kulliat is by definition a posthumous body of works but now you can have one when you are still alive

PHOTO: AINY KAMRANI

‘Diwan Bahadur’ is also a title of honour awarded during the British Raj to prominent people while in law and judiciary a cognate word, Diwani, detonates ‘civil cases’ as opposed to the ‘criminal’ or ‘Faujdari’ ones. But, for a student of literature the word Diwan has only one meaning: a collection of poetry.

Nevertheless, again in this sense, the word is not free from its pitfalls. Every poetry book is not a Diwan – an almost obsolete tradition of arranging poetry radeefwaar, that is, collecting poetry of a single poet with all pieces alphabetically arranged according to the last letter of the couplet.

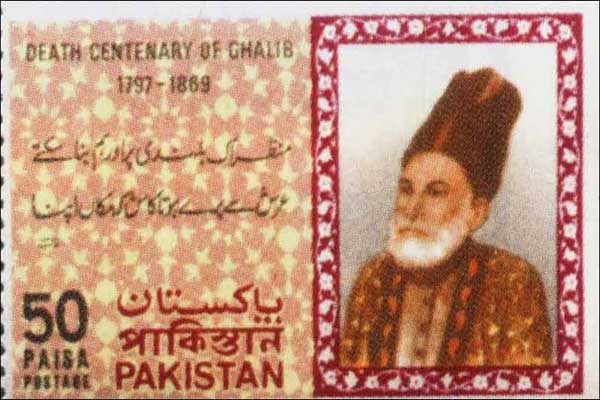

That was quite a challenging task as to compile a complete Diwan not only one had to compose ghazals ending with each and every alphabetical letter, but every ghazal required to have a Matla (the starting couplet), Maqta (the ending couplet containing the poet’s Takhallus of penname) and a set amount of couplets, traditionally, in odd numbers. Thus, when Ghalib came out with his slim and somewhat fragmentary Diwan, one Abdullah Khan Auj quipped:

Dedh Juz Per Bhi Hay Matla-o-Maqta Gha’ib

Ghalib Aasaan Nahi Sahib-e-Diwan hona

Just a paltry leaflet with neither an opening couplet nor the closing one

To compose a Diwan, O Ghalib, is not such an easy task.

PHOTO: FILE

PHOTO: FILEDespite the fact that occasionally one can spot a few examples of sticking to the Diwan tradition, composing of a Diwan, on the large, is a thing of past. Interestingly, Nasir Kazmi had named his second collection of ghazals ‘Diwan’, but that book has, as we know, no traditional Diwan arrangement and the poet had apparently only wished to pay tribute to the classical mannerism.

The Diwan tradition gave way to ‘Majmooa’ which is just a collection of poetry with its own name as we see it with the different collections of poetry by Iqbal –Bang e Dara, Baal-e-Jibreel etc.

In this formation you do not follow the Diwan arrangement, but are also free to include Ghazals as well as non-Ghazal poetry, even you can mix both of them in one Majmooa.

This loose pattern is used for prose collections as well, but in that case such books are largely composed of a single genre; short story, pen-sketches etc.

However, the second half of the twentieth century has witnessed another development – the phenomenon of Kulliat, which include the complete works of a writer, usually poet.

Well, many classical poets, especially those of more prolific type, used to have more than one Diwan, but, neither did they name them Kulliat nor even had they any concept of such composition whatsoever.

Technically speaking, a Kulliat, is not confined to poetry or any specific genre, yet it is mostly the poetry that is offered in this form partially because of the relatively slim size of a poetry books in comparison to the voluminous works of a novelist and even a short story writer.

We have, for example, the complete works of Premchand that spans over 24 volumes. But even the most productive of poets do not have such huge amount of works. Normally, a Kulliat of poetry comes in single, maybe, hefty volume.

Yet another development and a comparatively recent one is giving Kulliat an independent name, though, this practice has yet to become a full-fledged norm.

Thus we have ‘Sar O SaamaaN’ as Akhtarul Iman’s Kulliat, but the complete works of Nun Meem Rashed does not have its name as such – it is just Kulliat-e-Rashed. Same is the case with one of his contemporary poet Meera Ji, who has ‘Kulliat-e-Meera Ji’.

Lately, Kulliat has taken one new dimension, which may be termed a literary heresy.

Now you can have Kulliyat when you are still alive. Kulliat is by definition a posthumous body of works, a nachlass, or, for that matter, your complete works when you have already stopped writing – something unheard of in case of a writer.

PHOTO: FILE

PHOTO: FILETo have a Kulliat, the whole oeuvre, for you as a living writer – a poet, means that you have already finished your writings but paradoxically you are still writing.

Zafar Iqbal is getting his multi-volume Kulliat being published; five volumes have already seen the light of the day. He has named his Kulliat ‘Ab Tak’ [Till Now].

The very provisional nature of the name suggests ambivalence on the part of the poet who calls his project a Kulliat; complete works, but in the same breath he tells us that it is still in progress.

Interestingly, the poet is including those books in this Kulliat too that were never published before. An unpublished book is definitely to be a part of your Kulliat, but that is to be done posthumously.

Further, it not only with the writers who have already played their innings or have passed away, even the younger generation, still producing actively, is also coming out with Kulliats.

A few day ago, while telling me the news of her recently published Kulliat, a contemporary poet from comparatively younger generation said: “Well, it looks somewhat odd to have a Kulliat; some would even consider it a bad omen, but my publisher insisted to bring it out telling me that the following books would be included in the subsequent editions of the Kulliat.”

Does this mean that our writers are submitting to the dictates of market economy? If so, it is being done at an added burden on the reader’s pocket.

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ