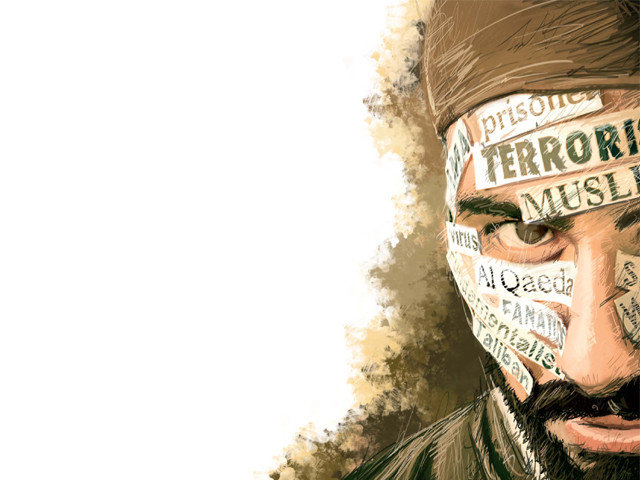

Counter terrorism: Strategies remain blur, realities get harsher

Conference on security situation of Pakistan held at QAU.

Despite being the worst victim of terrorism, Pakistan has yet to evolve a counter-terrorism security discourse which enjoys popular acceptance and legitimacy. The delay has in turn jeopardised the efforts being conducted to fight this menace. Dr Rifaat Hussain, head of Department of Defence and Strategic Studies at Quaid-i-Azam University, expressed these views on Saturday.

He was addressing a two-day conference on “Development Challenges Confronting Pakistan”, organised by the American Institute of Pakistan Studies. The conference aimed at rectifying the void by bringing together scholars and practitioners to develop understanding of structural barriers impeding the growth of the country.

At the event, Dr Hussain spoke on “Pakistan’s Security Discourse after 9/11: An Appraisal”. He noted that following the 9/11 attacks, Pakistan became a frontline state in the US-led global war on terror. Having made common cause with Washington against al-Qaeda, Islamabad was forced to articulate a new security paradigm in which the logic of its rivalry with India sat uneasily. The focus then had to shift from the old arch enemy of India to the new nemesis, al-Qaeda. But, Hussain said that this transition was not a smooth one, leading to delay in action on many fronts.

Moreover, Christine Fair presented her paper on “Poverty and Support for Militant Politics: Evidence from Pakistan”. She said that combating militancy and violence, particularly in South Asia and the Middle East, stood at the top of the international security agenda. Much of the policy literature in this regard, she said, focused on poverty as a root cause.

To address the question, she referred to a nationally-representative survey, which has been based upon responses from 6,000 Pakistanis on militant organisations. The study revealed three key patterns.

First, Pakistanis exhibit a negative affect towards such organisations. The people from the areas where such groups have conducted attacks dislike them the most. Second, contrary to conventional expectations, poor Pakistanis dislike militant groups more than middle-class citizens. Third, this dislike is strongest among poor-urban residents, suggesting that the negative relationship stems from exposure to the externalities of terrorist attacks.

While addressing the conference on “Pakistan’s Political Development: Looking backward, Looking Forward”, Ashley Tellis was of the view that unrestricted bureaucratic (civil and military) power had impeded the development of democratic institutions in Pakistan. He underlined the need for a stable constitution that creates norms, culture and standard for political development. He noted that Pak-US relations were oriented towards meeting very narrow national objectives, which sometimes leads to difficulties between the two allies.

He, however, insisted that Pakistan was not “facing the danger of a state failure” after identifying ambiguous commitments to democracy, continuous economic stress, deficit of recourses and limited number of alternatives as major factors behind hindering development.

Published in The Express Tribune, May 8th, 2011.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ