Manto vs Mantu: What’s in a name?

A look at mainstream Urdu names and why some of them have so many different spellings and pronunciations

PHOTO: FILE

While putting this now proverbially famous dialogue in Juliet’s mouth, Shakespeare must not be aware that he was anticipating the radical theorisation of Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, who claims that all ideas about the structure of language are dominated by a principle of sheer arbitrariness.

The theory, as we know, was later to colour almost the entire spectrum of social sciences and cultural studies in 20th and 21st centuries. This was the idea which led to the emergence of the structuralist anthropology of Levi-Strauss, who employs Saussurian insight to understand thought-patterns of different cultural groups; radical psychology of Jacque Lacan, who famously claims that the unconscious is structured like a language and also ‘deconstruction’ of Jacques Derrida, who proposes that ‘pure language’ cannot be reduced to single meanings and stresses ‘multiplicity’ and ‘insatiability of meaning’ in a text.

This essential element of arbitrariness in the human language, however, could not diminish the role, value and our interest in names and naming. In spite of all these ideas, onomastics – the scientific study of names – has been establishing itself as a multidisciplinary area and ‘literary onomastics’ now seeks to study the function of names and naming in literature from many different perspectives.

But what about the names of writers? Leaving aside the traditional use of pen-names, pseudonyms, and the takhallus – the short name a poet adopts, and in some cases, uses in his poem to put his signature at the end – there are issues of spelling and pronouncing their names, including both the proper names and surnames.

Urdu, as is the case with many other languages, uses a script that is not so articulate to bear the burden of certain sounds. The difficulty arises, especially, in exotic names.

Traditionally, we have had problems in pronouncing continental names – Sarte, Camus etc – but now, thanks to our relatively direct exposure to the European languages, we tend to pronounce such names in the way there are pronounced by the native speakers.

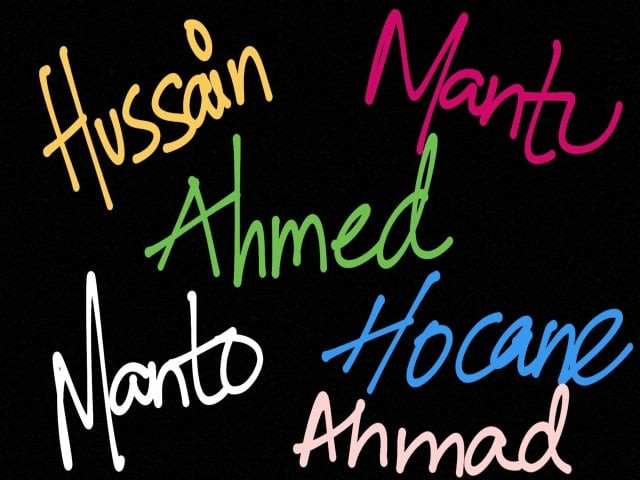

The problem stands also with our own names. We write certain names, in more than one way: Hussain, Hussein, Hosain, Husain and even Hocane! We’ve got Intizar Hussain, Aamer Hussein, Attia Hosain and me, Aftab Husain!

‘Afzal’ and ‘Afzaal’ can be well differentiated when written in the Perso-Arabic script but create problems in Roman letters. The standard spellings of ‘Iqbal’ are the same as we find in the name of Allama Iqbal, but a famous Pakistani political scientist and activist Eqbal Ahmed always preferred to write his name starting with E. There is a disagreement on ‘Ahmad’ and ‘Ahmed’ too. The list is infinite and shows an anarchy in our onomastic orthography

The surname of the famous short story writer Sa’adat Hasan Manto is not without a problem. Should we call him Manto – as he is generally pronounced – or Mantu – as the writer had reportedly wished to be called and is arguably, the correct pronunciation of his last name? Seen in the list of problematic names of writers listed above, his surname presents even an added problem: it is not only spelled differently but also pronounced differently.

A Pakistan researcher Dr Ali Sana Bukhari claims that ‘Manto’ used to tell his daughter Nuzhat that his surname rhymed with ‘One Two.’ Bukhari, relying on the authority of The History of Kashmiri Castes [Tareekh-e-Aqwaam-e-Kashmir] by Muhammad Din Fauq, tells us that ‘Mantu’ is not the caste or sub-caste of our writer, but an appellation.

Bukhari uses a Punjabi word: ‘al’ that signifies an appellation given to a person or family for certain behaviour and characteristics. That appellation gradually stuck as a surname to the family. Fauq relates even detail of the nomenclatural process of Mantu.

Well, Manto was a proud Kashmiri Pandit, that is, Brahmin by caste, we all know. Iqbal was famously a Kashmiri Brahmin too, Sapru by caste. We have a lot of other surnames of famous Kashmiri Brahmin ending with ‘U.’ These include India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Indian nationalist leaders Saifuddin Kichlu and Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, one of the prominent politicians of India after partition Kailash Nath Katju and famous linguist Braj Bihari Kachru. Why not call it Mantu, instead of Manto?

Interestingly, one of the celebrated grandnephews of the short story writer – himself a famous leftist intellectual and legal activist – writes his surname neither as Manto, nor Manto, but Minto. I am talking about Abid Hassan Minto.

In my childhood, I was under the impression that the writer Manto and Lord Minto are one and the same family names as it was not uncommon to hear people calling the former Minto.

So, we have three possibilities, three variations – Manto, Mantu, and Minto. We may, perhaps, brush aside the last option considering it’s merely an attempt to Anglicise one’s name, as we sometimes spot Geoffrey instead of Jafri, or ‘Shah’ written as ‘Shaw.’

Mantu, however, seems to be a strong competitor.

Have something to add to the story? Share in the comments below.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ