How can Pakistan effectively eliminate virus, mosquito

Modern strategies must include biological means to genetically modify, eliminate vectors

Modern strategies must include biological means to genetically modify, eliminate vectors. PHOTO: REUTERS

Despite that, the authorities have yet to develop any specific drug or potent vaccine against dengue.

Pakistan at risk of chikungunya spurt

In the current situation, where all the four virus serotypes of dengue have been detected in the country, vector control through the biological and chemical means along with social mobilisation, continuous vector surveillance, a collaboration of various healthcare units and much-needed legislation for environmental management would make for an effective dengue elimination strategy.

Mosquito behaviour

There are over 3,000 species of mosquitoes, but only a few feed on the blood of humans including Aedes aegypti - the major vector responsible for the transmission of the dengue virus.

The mosquito not only transmits the dengue virus – which has already cost 18 lives in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa this year - but has also been reported to transmit the yellow fever virus, the West Nile virus and the chikungunya virus.

Adult Aedes mosquitoes are jet black, with white spots on their body and white rings on their legs. They are among the deadliest creatures on earth.

They can breed in a teaspoon of water, and their eggs have been found in tin cans, bottles, jugs, flower vases, cups, tanks, tubs, storm drains, cisterns, cesspools, catch basins and fish ponds. This implies that the mosquito can lay eggs in nearly anything which can hold a few drops of water for some time.

Brace yourself for new mosquito-borne disease

These mosquitoes are relatively easy to breed and cost almost nothing to transport. Aedes aegypti neither fly far nor live for very long; it would move a few hundred yards and, on average, survive as an adult for ten days.

But it is a tricky insect to detect.

Most mosquitoes are noisy enough to wake a man from his slumber and slow enough that they can perhaps bite once before being swatted.

The Aedes aegypti, on the other hand, work silently. Attracted to human odour, they strike in silence. Though they love to feed during the day, they mostly hunker close to the ground and bite people on their ankles or legs.

The mosquito is also highly sensitive to motion—as you move, it will, too, often stabbing its victim several times during each feeding cycle, picking or depositing viruses with every bite.

For reproduction, Aedes usually deposits their eggs in multiple locations which increase the chances for their eggs to survive.

On average, a female Aedes lays around 300 eggs during her life - all of which are full of viruses.

These eggs can survive in the environment for months and years. On ‘hatching’ they can grow to infected mosquitoes whenever suitable conditions are met.

Since the mosquito cannot travel far, the viruses are carried from place-to-place through infected eggs which stick to goods and people’s belongings.

Zika virus mosquitoes found in Pakistan

Poor urban infrastructure facilitates the breeding of Aedes by providing more breeding places which are not accessible for chemical treatments.

Aedes aegypti thrive in hot and humid climate and has adapted to urban environs with great dexterity. Even the most effective modern larvicides often miss the mosquito’s well-hidden urban breeding grounds.

In our peculiar social settings with distinct social habits which favour environmental fragmentation, vector-borne diseases such as dengue would disappear only temporarily due to unsuitable environmental conditions, but re-emerge nastier than before whenever growth conditions are optimum.

It is necessary to understand that the last 10 days of the Aedes adult life are important for the transmission of dengue or other viruses and that the virus has to stay inside the mosquito for some time before it is transmitted to another person.

The small radius it can travel means that if someone in the family is infected, one should take every step to get rid of mosquitoes in or around their houses and apply repellents regularly on the skin as well as on clothes.

Controlling mosquitos

Preventing or reducing dengue virus transmission is hinged entirely on controlling the mosquito vectors or interrupting the human–vector contact.

An effective control strategy, thus, must engage policymakers, control managers, social mobilisers, health, environment and urban planning departments.

Dengue fever infects over 12,000 in Pakistan

The baseline for a control strategy lies in surveilling the Aedes species or incidence of dengue in particular areas. It is, therefore, necessary to have a continuous vector surveillance programme in place which works throughout the year and activates a diseases-early warning system for timely interventions in the event of a possible epidemic.

Research has indicated that vector surveillance and eradication during the non-breeding season (December to May) proved more efficient in reducing the number of dengue infections during the breeding season.

Aedes uses a wide range of confined larval habitats, both man-made and natural. Methods of vector control include the elimination or management of these habitats, larvicide with insecticides, using biological agents, the use of genetically modified mosquitoes and the application of adulticides.

Environmental management is at the heart of a vector control programme. It includes some environmental modifications such as piped water supply, environmental manipulations such as the management of “essential” containers, such as frequent emptying and cleaning by scrubbing of water-storage vessels, flower vases and dessert room coolers; cleaning of gutters; sheltering stored tyres from rainfall; recycling or proper disposal of discarded containers and tyres; managing or removing plants such as ornamental or wild bromeliads that collect water in the leaf axils from the vicinity of homes, and installing mosquito screening on windows, doors and other entry points, and using mosquito repellents and nets while sleeping during daytime.

Since the mosquito cannot survive without water, a careful control strategy would always ensure water piped to households, discourage water drawn from wells, communal stand pipes, rooftop catchments and other water-storage systems.

Viral disease: Is Lahore at risk of Chikungunya?

Water containers should be tightly sealed with lids or a mesh. Moreover, expanded polystyrene beads should be used on the surface of the water to provide a physical barrier which stops mosquitos from gaining access.

Solid waste management is another important area which includes proper disposal of non-biodegradable items of household, community and industrial waste.

Unfortunately, we do not have a good waste disposal system which leads to the spread of a number of infectious diseases, including dengue.

Although there are a variety of chemical options to kill the larvae or adult Aedes species, research has indicated that an integrated biological, chemical and environmental management practices give promising results.

This combinatorial approach has successfully reduced or transformed Aedes population in Brazil, Singapore and several other countries.

Fumigation is recommended to control a massive adult vector population only in emergency situations to suppress an ongoing epidemic or to prevent an incipient one.

Space spraying is however controversial for various reasons including its impact on human health and other species while its efficacy in open spaces lasts only for a few of hours.

In densely populated areas, where access to habitats is difficult, vector populations can be suppressed through fumigation released by low-flying aircraft.

However, other countries have had success with insecticide treated materials (ITMs) such as nets and lethal ovitraps at different places around cities.

Biological control

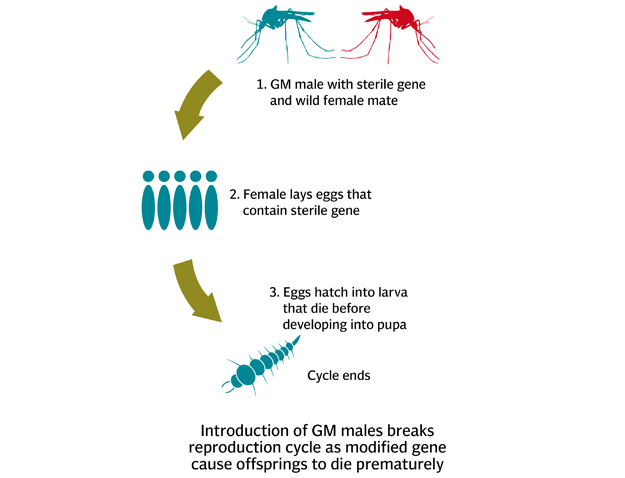

While there are a number of biological options to control Aedes, modern technology enables us to deal with the mosquitoes by changing their genetic makeup in such a way that either they die before they can transmit the virus, or they produce progeny which cannot reproduce further.

No more bug spray: This TV comes with a mosquito repellent

One way is to use the Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes with a short life span. These mosquitoes can be raised in laboratories in the millions and have successfully been used in Brazil and Singapore for their ‘eliminate dengue programme’ to reduce the vector population and the burden of dengue.

Some researchers have manipulated the genomes of mosquitoes. These modifications either shorten the life span of or cause sterility and death of the transformed Aedes species.

Field trials of these genetically modified mosquitoes have been successfully been carried out in Malaysia, French Polynesia, Brazil, Australia, Vietnam and Singapore.

Several laboratories and companies, including British firm Oxitec, are producing genetically engineered mosquitoes.

But it is very important to build our local capacity to produce such mosquitoes as a major component of biological control in order to strengthen efforts to eliminate dengue and other virlal infections.

The first dengue vaccine, ‘Dengvaxia’ introduced recently has been reported to be moderately effective. Its efficiency against the locally prevalent dengue virus types is yet to be determined because of the vast differences in the genetic makeup of vaccine strains and locally prevalent strains can not only render the vaccine in-effective but even lead to a disaster in the form of more dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome cases.

However, to deal with dengue, we need to ‘vaccinate if it is safe to do so after careful trials have been conducted’.

Dr Ijaz Ali is a virologist and associate professor at CIIT Islamabad and has covered major dengue epidemics in Pakistan. Dr Imtiaz Ali Khan is the vice chancellor of the University of Swabi and has served as the chairman of the Entomology Department at the University of Agriculture in Peshawar.

Published in The Express Tribune, September 18th, 2017.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ