The anti-poor bias of Karachi Circular Railway’s revival plan

Though government is quick to make poor people homeless, it ignores the factories and petrol pumps on KCR land.

PHOTO: HINA JAVED

Ahmed Raza, a once devoted traveller of the inter-city railway system, walks in the direction of a dingy shack. He stops and looks at all the other houses in the settlement. With a grim expression on his face, he reminisces the time when there was no Azeem Khan Goth and the place was instead a bustling railway station. Today, the dilapidated shanties serve as a sad reminder of what was once a popular mode of public transport in the city.

Azeem Goth on a Friday afternoon. PHOTO: HINA JAVED

Azeem Goth on a Friday afternoon. PHOTO: HINA JAVEDTrack route and history

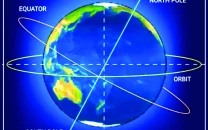

The circular railway is a looping network of 30 stations that links the five most important work areas of Karachi; Central Business District, S.I.T.E, Landhi Korangi Industrial Estate, Steel Mill and the Port. It became operative in 1964, as part of a vast network of stations and junctions intended to cater to the growing demand of transport in Karachi. The 43-kilometre-long track lays its foundation on the main line of Pakistan Railways at Drigh Road Station, crosses Sharah-e-Faisal and passes through the industrial and commercial centres of Karachi, such as II Chundrigar Road and Wazir Mansion. A few miles ahead, the track crosses Lyari, where the river is polluted by the waste discharged from factories and households. It further extends to Nazimabad, Liaquatabad, and Gulshan-e-Iqbal and finally touches Drigh Road, completing a full circle.

By the late seventies, the circular railway was making 104 trips per day and had become an essential means of transport. It is estimated that at least 300,000 commuters once traveled on the KCR every day. However, its effectiveness slowly declined as it started running at a loss in the mid-eighties. Various reasons have been given for its discontinuation. It has been said that by the late 1980s, corruption and drug trafficking were rampant along its route. Another version says there were frequent attacks by “criminals” on the railway, and that the owners of minibuses were responsible for the problems faced by the KCR. Finally, in December 1999, KCR services were discontinued. Since then, the railway land has come under immense pressure to meet the needs of the city.

A decrepit car submerged in a garbage dump along the tracks of KCR. PHOTO: HINA JAVED

A decrepit car submerged in a garbage dump along the tracks of KCR. PHOTO: HINA JAVEDInformal settlements

Since KCR was shut down in 1999, the area around the railway track has been encroached by people from low-income groups as well as multinational companies looking for a piece of land in the ever-growing megacity. Azeem Khan Goth is one such settlement; another is the PWI Colony near the City Station off II Chundigrar Road.

When KCR was functional, the City Station was a bustling place but now it is usually filled by a quiet that is deafening and is broken only by the noise of a few people who come to catch their train in a rush. Today, the oldest station in Karachi is mainly used as a bypass for freight traffic.

PWI Colony hidden behind narrow lanes at the City Station. PHOTO: HINA JAVED

PWI Colony hidden behind narrow lanes at the City Station. PHOTO: HINA JAVEDOn the furthest right of the station lies PWI Colony, well hidden behind the narrow lanes, infested in encroachments in the shape of shops and stalls. Car horns, shouting voices, and the sounds of Azaan, mingled with the snarling engines of rickshaws stalled in traffic, add liveliness to this slum where slightly wealthier residents live, compared to Azeem Khan Goth. The residents of PWI Colony acknowledge that the land belongs to Pakistan Railways, but duly pay rent to those who established the colony albeit illegally. These land grabbers rule the territory, and no man in the neighbourhood dares to question their authority. “Every month, we pay the house rent to our ‘landlords’,” Najma, a resident, rumbles as she swings the fan to keep her daughter cool in the scorching afternoon heat.

What appears like a lawless system in Karachi is actually governed by a set of informal but strict rules. At PWI Colony, the boys of the land grabbers appear markedly superior to the tenants. Azam, the son of one such person, wears a black kurta and sits on a cart sipping tea with his friends. “We are the owners of PWI Colony, but we do not charge money from anyone,” he says proudly. “We do this ‘Allah wastay’.” He quickly offers to show the proof of land ownership, which is heavily forged according to some authorities.

Freight trains at Karachi City Station. PHOTO: HINA JAVED

Freight trains at Karachi City Station. PHOTO: HINA JAVEDInterestingly, Javed Iqbal, Assistant Sub-Inspector of the Railway Police, blatantly denies the presence of any settlement at or near the City Station. He claims that the police and government have done a remarkable job in uprooting the informal settlements along the tracks. “The railway police are so efficient that they wipe out the encroachers before they can even think of establishing their houses,” he says authoritatively.

However, according to urban planner Arif Hassan, these claims are nothing but an eyewash. “They [the railway police] are equally involved in the construction of katchi abadis,” he says.

Revival plans

In the 17th century, Karachi was called Kolachi-jo-Goth. The city started life as a fishing village. However, during the British Raj, the village came under the urban sprawl which resulted in industrialisation. Some parts of the city were taken over by the government and others were neglected to such an extent that it resulted in today’s haphazard urbanisation. According to an Asian Development Bank study of 2005, nearly half of Karachi’s urban population lives in squatter settlements.

Five-year-old Saima plays adjacent to the tracks of the circular railway. PHOTO: HINA JAVED

Five-year-old Saima plays adjacent to the tracks of the circular railway. PHOTO: HINA JAVEDThese informal settlements are the first to bear the brunt of state’s highhandedness whenever a development plan is to be implemented in the city. And plans to revive the KCR are no different. Hasan, who is also the founder of Urban Resource Centre (URC), has been working on projects to study the feasibility of the revival and resettlement plans and he describes the latest one as insensitive and bureaucratic with a strong anti-poor bias. “This plan offers unlimited jobs for the government and vast amounts of money for the consultants at the cost of poor people,” he says.

URC Director Younus Baloch adds that some of the informal settlements along the KCR line have been bulldozed by the government as part of the revival plan but it eventually became evident that these settlements were demolished so swiftly because the residents were vulnerable members of the society who could not protect themselves. As a result, Baloch says, many organisations were formed to present their claims and guard their gains.

Kausar, a 38-year-old resident of Azeem Khan Goth, is one such person. She demands compensation for the loss of the houses owned by her ancestors in the area. “We shall continue to live here till we get justice,” she says defensively. “And, if we die, our children are ready to continue. This is our land and we have a right to live here.”

Resident Kausar keeps an eye on her children as they play outside. PHOTO: HINA JAVED

Resident Kausar keeps an eye on her children as they play outside. PHOTO: HINA JAVEDAccording to Hasan, the government has consistently failed to provide compensation that was promised to illegal occupants. “Housing is a fundamental human right that cannot be denied to a country’s citizens,” he says. When asked whether it is fair for eight people to live in a single room, he says, there is nothing they can do about it. “They don’t take that much as social injustice. It is only when those eight persons are thrown out into the open air by the government – that is social injustice.”

‘Formal’ settlements

Though the government is quick to make people living in informal settlements homeless as part of revival plans, it does a good job ignoring ‘formal’ settlements such as residential buildings, factories and petrol pumps on the KCR land.

In a report titled “Land, CBOs and the Karachi Circular Railway” by Hasan, the government that came to power in the democratic elections of 1999 planned to implement the master plan for KCR revival. What was missing in the plan was a resettlement scheme for the illegal ‘formal’ developments within the bounds of the mainline. These established settlements are those where some of the multinational corporations exist without ever being questioned by the authorities. Hasan condemns the government’s dismissive attitude with regard to the uprooting of formal settlements. “Almost 72% of the encroached railway track is made up of commercial plazas, residential apartments, buildings, shopping centres and petrol pumps,” he says regretfully. “Only 28% of the encroachment is by the low-income groups. Yet they remain at the forefront of the controversy.”

An undulating landscape of garbage in one of the narrow lanes of PWI Colony. PHOTO: HINA JAVED

An undulating landscape of garbage in one of the narrow lanes of PWI Colony. PHOTO: HINA JAVEDCommenting on government’s disinterest in wiping off the ‘formal’ settlements for KCR revival, Senior Superintendent of Railway Police Captain Chaudary Muhammad Asad Ali says “it’s impossible to uproot entire manufacturing plants”. “A price is negotiated for letting these factories continue their operations,” he admits.

According to him, the concerned authorities have successfully retrieved a total of 2,618 acres of land in the last two years. “The problem in Pakistan is that everything is happening everywhere,” he says in comparison to the developed countries where everything is done in an organised manner.

Like many others, he also dreams of a time when Karachi will be free of encroachments but is not very hopeful. “Government officials talk about providing houses, jobs, and recreation to the displaced. But, I find it hard to imagine this being implemented.”

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ