Schizophrenia and our Supreme Court

Non-medical definitions, outdated precedents behind unfortunate verdict against Imdad Ali

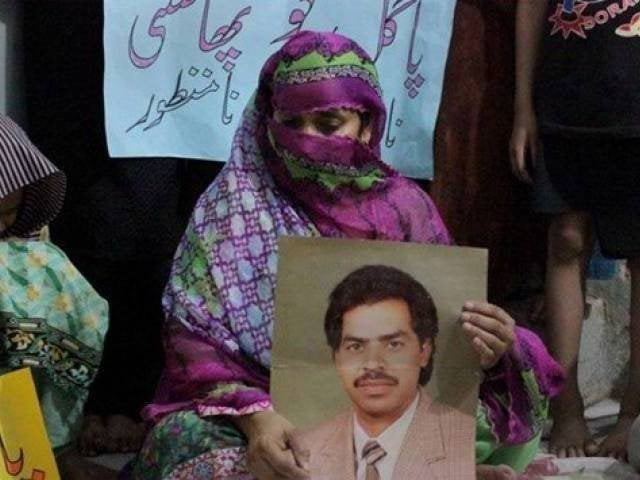

Ali, from Burewala district of southern Punjab, was awarded death sentence in 2002 in a murder case. PHOTO: ONLINE

This judgment was passed in a petition filed by death-row prisoner Imdad Ali’s wife to delay his execution on the grounds that he was mentally ill and therefore be allowed time to get medical treatment to be able to prepare his will.

SC upholds death penalty for mentally ill man

Ali, from Burewala district of southern Punjab, was awarded death sentence in 2002 in a murder case. The latest petition must be distinguished from his earlier appeal against the death sentence which was dismissed by the Supreme Court in October 2015 and the mercy petition which was dismissed by the President in November 2015. The judgment in the present Supreme Court case followed the dismissal of the same request in the Lahore High Court in August of this year and is based on the Court’s understanding of schizophrenia.

It is unfortunate that the Mental Health Ordinance, though dealing in large part with the management of the property of those suffering from a mental disorder, does not make any reference to the manner in which such a person can make a will. However, that lacuna is not the source of current public dismay. Instead the reason is the glaringly obvious failure of the judgment in deeming it “appropriate to ascertain what schizophrenia is” and then failing to take into account any universally accepted medical definition of the illness. Rather than looking at diagnostic tools – such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems – for guidance, the Court chose to rely on the dictionary meaning of the disease in New Webster’s Dictionary of the English Language and Merriam Webster’s online dictionary, among others. This lapse was highlighted by a group of doctors in their open letter to President Mamnoon Hussain titled “Save Imdad; Schizophrenia is a chronic and debilitating disease”.

Rights group urges Pakistan not to hang mentally ill man

In addition, the judges extrapolated upon two Indian cases from 1977 and 1988, the latter of which reached the jaw-dropping conclusion that “I do not use the word ‘schizophrenia' because I do not think any such disease exists…”. In fact, it is worth noting that the case judgment from 1988 (AIR 1988 SC 2260) was given in the context of a dissolution of marriage. So not just is that judgment almost three decades old, but it also dealt with circumstances which had less at stake than the current case, in which the outcome determines whether an individual’s right to life will be upheld or not. There is no doubt therefore that Ali’s case requires deeper scrutiny than simply a repetition of an apparently dismissive and uninformed judgment from 1988. This is especially true when looked at it in the context of the advances that medical sciences have made in recent years in relation to understanding mental illness in general and schizophrenia in particular. In short, therefore, it is clear that the Court gave its binding judgment on what schizophrenia is without taking into account the years of medical research that have gone into doing just that.

The consequence of the judgment’s reliance on non-medical definitions and outdated judgments was the conclusion that its lack of permanence meant that schizophrenia did not fall within the statutory definition of mental disorder. This is worrying on two fronts: Firstly, that it is now internationally acknowledged by medical science that the condition is in fact largely permanent, with medication only being able to manage but not cure the disease. Secondly, the requirement of permanence, on which the judgment heavily relied, is not actually a statutory requirement. “Mental disorder” in the Ordinance is defined, not with a single definition, but as covering a spectrum of mental illnesses, from mental impairment, severe personality disorder to severe mental impairment. While the definition of one of these three types, namely severe personality disorder, requires there to be a “persistent disorder or disability of [the] mind”, the other two defined types of mental disorder do not make any reference to the requirement of permanence at all. Even further, the Ordinance provides a catch-all provision to include “any other disorder or disability of mind”. The bottom line is that for the Supreme Court to determine that a recognised and admittedly severe mental illness does not fall within the wide definition in the Ordinance is clearly to misconstrue Parliament’s intentions.

In any event, irrespective of whether the condition is temporary, permanent or intermittent, it appears that in getting entangled in the definition of mental illness, the Court lost sight of the real issue: Whether a prisoner suffering from a diagnosed mental illness can be executed. This issue must be looked at in light of the circumstances at the time that it came before the Supreme Court and not in light of whether mental illness was established as a defence to the crime in earlier judicial proceedings. However, the Supreme Court placed undue emphasis on the latter without analysing the former in light of Pakistan’s national and international obligations. To this end, no mention was made of the fact that execution of a mentally ill prisoner is prohibited under customary international law. In particular, the Court did not take into account the UN Safeguards Guaranteeing Protection of the Rights of Those Facing the Death Penalty (1984) which prohibits execution of “persons who have become insane” or the resolution adopted by the UN Commission on Human Rights (2000) urging countries that retain the death penalty not to impose it “on a person suffering from any form of mental disorder”.

SC rules schizophrenia is 'not a mental disorder'

The Court’s archaic view of the meaning of mental disorder coupled with its failure to scrutinise Pakistan’s obligations holistically, culminated in a decision that can only be viewed as a breach of human rights for all mentally ill prisoners on death row. As matters currently stand, the Pakistan Prison Rules 1978 provide for the procedure to be followed in the case of a mentally ill prisoner. In particular, Rule 441 requires that a mentally ill prisoner be transferred to a psychiatric facility. However, contrary to its international obligations, Pakistan does not have laws categorically prohibiting the execution of those suffering from a mental disorder. Therefore, with a case like Ali’s which has been in the public eye, the Supreme Court had an opportunity to flex its judicial muscle and spearhead the understanding and acceptance of basic human rights in such cases – even if it was just to the extent of the right to draft a will. Regrettably, however, that did not transpire. Instead, no matter what one’s opinions regarding the death penalty are, the unfortunately drafted judgment is nothing short of a miscarriage of justice and a drastic setback to medical advances in the already stigmatised area of mental disorders.

Hiba Thobani is an advocate who runs the legal aid not-for-profit 'Qaaf Se Qanoon', coaches law students in advocacy skills and believes in the inherent power of the law to do good.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ