Budgeting for 2016-17

Ishaq Dar unveiled a Rs4.4 trillion budget on June 3, kicking off his speech by praising the government’s achievements

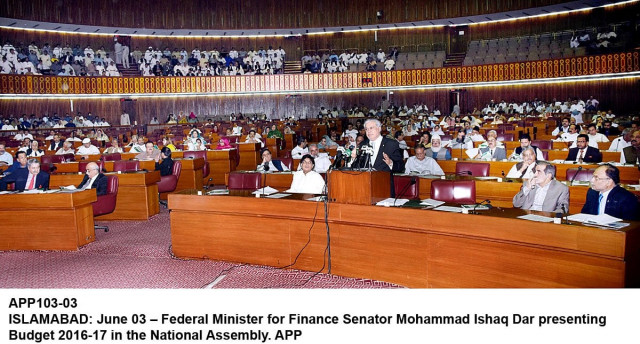

Finance Minister Ishaq Dar present the 2016-17 budget in the National Assembly on FRiday. PHOTO: APP

The budget had a pro-agriculture tinge to it, where massive incentives and concessions were announced for farmers. The relief comes on the back of a contraction in the sector this outgoing fiscal year, prompting economic managers to give a rethink to the neglected area. But measures announced were not long term in nature. Reduction in tariff for agricultural tube wells and availability of financing may encourage investment, but it will not transform the sector into a driver of growth. The measures may pull some farmers out of their misery and may even motivate them to continue farming, but hoping that this would be enough to take GDP growth beyond five per cent would be a massive stretch. However, it may satisfy some parliamentarians and their rural vote banks — this seems to be the main aim for the time being.

When you break down budget numbers, one quickly realises that there was no out-of-the-box thinking to increase tax revenue. Instead, what we saw was more of the same — increase rates on those who contribute to the national kitty, while conveniently leaving those out who don’t. One measure that raised eyebrows was increasing the threshold for National Savings Schemes, where the upper investment limit per person was increased from Rs4 million to Rs5 million. The scheme is aimed at senior citizens who have retired and is meant to mobilise more funds available to the national savings centre, which uses the money to finance budgetary requirements. This is not a growth-led measure and will only increase rent-seeking. Meanwhile, approving the zero-rated tax regime for five export-oriented sectors may help them out, but it may still not increase exports because these sectors suffer from issues of competitiveness and innovation, with regional competitors having left them far behind. Their lower cost may help them increase their margins, but the tax exemptions will have to be compensated through higher tax rates elsewhere.

Every year the public hopes that budget measures help the poor as a balance is found between growth and incentives. However, what we see is a combination of incentives to those who make the most noise and perform the worst. These are often meant as handouts to neutralise protests, while creative measures remain missing. Pakistan goes from budget to budget, increasing tax rates and penalising those who already pay. If we take the government to be the household head and rest of the family members as various sectors of the economy, it would basically mean that there are one or two children who are being spoilt rotten, while the rest remain ignored. One hoped that the government would move from fiscal consolidation to promoting growth. That didn’t happen.

Published in The Express Tribune, June 4th, 2016.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ