The position will remain vacant, not because we do not have eligible candidates, but because the political system we follow does not provide space for outsiders to rise to the top.

But surprisingly, the most complicated electoral system in the world has no such barriers. Otherwise Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders — both classic Outsiders —would not be in the strong position they are in the US presidential campaign. Or consider the present White House inhabitant. Barack Obama was a virtual unknown — a first-time senator — but he burst onto the national scene with an inspiring personal story, an uplifting message of ‘Yes We Can’, and a promise of change. He was the Outsider whose time had come.

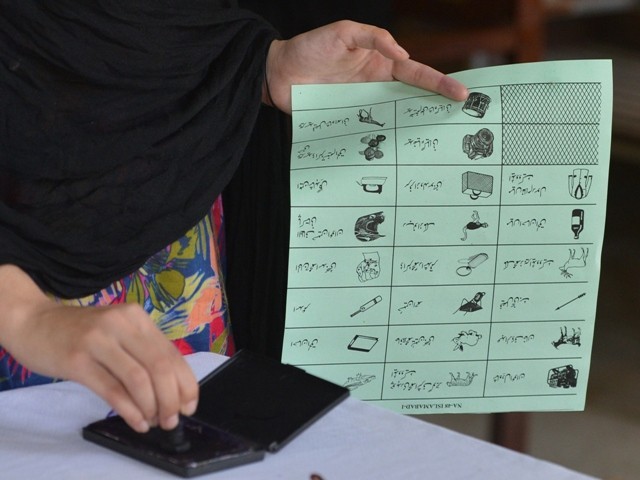

A year on: Inaction paralyses electoral reforms panel

And he broke new ground. In a recent article, The New York Times said: “Before Mr Obama’s victory, the ticket to a major party presidential nomination since John F Kennedy had been a well-seasoned national pedigree or a stint in the governor’s mansion. Consider Lyndon B Johnson, Richard M Nixon, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, both George Bushes and Bill Clinton. Mr Obama, then, is the clear outlier in that list in terms of legislative or executive experience.”

What gives rise to the rise of the Outsider, and why is Pakistan immune to it?

When the electorate is angry, or when it is yearning for hope, it normally catapults an outsider to the top. Obama triggered hope, Trump is tapping into anger, and Sanders is drawing support from those who see Hillary Clinton as the ultimate insider Establishment candidate. There is a not-so-subtle theme running through these emotions: the ‘system’ does not care for the common people, and those who run this system can never break out of its limitations.

The US electoral system is one of the most complicated in the world. It is also one of the most decentralised federations among democratic nations. The states in America have their own legislative assemblies making their own laws to be implemented by their local executive branches. The president of the country can rarely override local laws and has almost nothing to do with the running of these states. Yet, the office of the President — often called the ‘Imperial Presidency’ — wields sweeping powers within the Executive as commander-in-chief of the armed forces, as well as making the budget (although Congress approves it), making key appointments and directing the foreign policy of the nation. He also has key veto powers over legislative agendas and bills.

Polling trends: Urban areas are detached from elections, stats show

With all these powers, he still has to work within an intricate and complex system of checks and balances. The most powerful man in the world bows to the authority of the local states, and must share power with Congress and the Senate in the Centre. But this system is built in a manner where the political Establishment (the Republican and Democratic parties) throw open their ranks to allow for their members across the country to elect their candidates who then face off each other in the November elections. No candidate is beholden to any party head, or senior member, or donor, or even a cabal of insiders. Yes, the party leadership and donors with deep pockets play a key role, but theirs is not the decisive one. Among the current candidates, Marco Rubio is the favourite of the Republican Party leadership, and yet he is trailing at third position behind Donald Trump and Ted Cruz.

This complex system allows for the candidate to test his or her mettle directly with the people.

Not here at home. An outsider in Pakistan has a negligible chance to aspire for national leadership. The electorate may be as angry, as resentful or as hopeful as an electorate can be, but it can only choose between the Sharifs, Bhuttos and Imran Khan. And within these three big parties, the top man (or woman) decides the career prospects of an aspiring candidate.

Everybody wants electoral reforms. There’s even a committee for it. Are sweeping electoral reforms a realistic possibility? Therein lies the rub. The reform that Pakistan’s system hungers for is not just introducing electronic machines, or training polling staff, or even ensuring campaign finance limitation — this is all important but essentially superficial. What we are looking for is reform that throws open the system to the best and the brightest; reform that ensures that candidates are not beholden to individuals or families; that the electorate has a wide choice of candidates who can present their messages directly to the voters.

Electoral reforms: ECP told to buy electronic voting machines by September

A presidential system? Not at all. Any time someone utters the word ‘presidential system’, people think of Ayub, Zia and Musharraf. Pakistan, we all hope, has outgrown this simplistic form of ‘change’ and is now gradually transforming into a complex democracy with checks, balances and the will of the people deciding who wields power through a mandate.

The limitations of the system are well known, none more so than the fact that it is monopolised by a few and barriers to entry are almost unassailable. Reform is difficult because powerful vested interests resist any change that dilutes their control. Devolving power to the provinces was the first major strategic reform within the system. It was resisted by those used to a strong Centre. Devolving power to the local bodies was the second major strategic reform. It was resisted by the provinces used to a strong provincial hold over all matters. Both these reforms have made the running of democracy more complex and difficult, but have empowered the people to a greater extent.

Now the Centre needs strategic reform.

Such reform will be resisted by parties that are afraid of losing their stranglehold over the system of electing the top office. If some type of a direct electoral system was considered for the highest office at the Centre, would it weigh against the smaller provinces? With provinces already fully autonomous, this fear loses its sting.

The US presidential campaign will dominate the global news cycle till the November election. It provides us a good opportunity to take a hard look at our own system and discuss out-of-the-box options that traditional democrats shy away from.

Here’s the question though: with all power brokers invested into the system, who will bell the cat?

Published in The Express Tribune, February 7th, 2016.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

1736372949-0/Untitled-design-(57)1736372949-0-405x300.webp)

1733707590-0/Jay-Z-(5)1733707590-0-165x106.webp)

COMMENTS (8)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ