There’s something happening in the province of Punjab that is not happening elsewhere: serious work. But some people fear the galloping disparity between the largest province and the others will feed into the feeling of alienation — for all the wrong reasons.

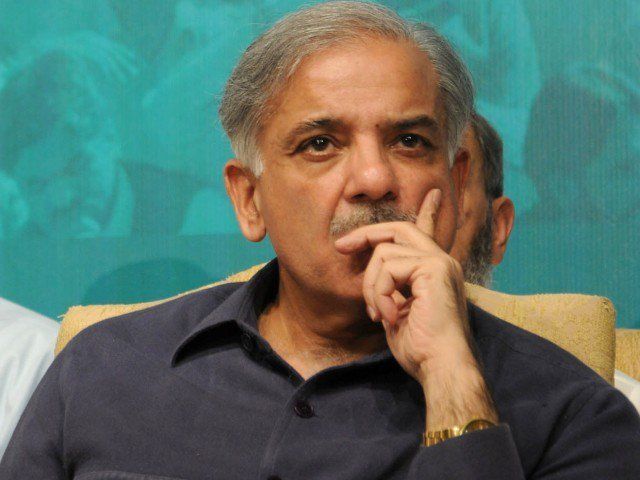

As 2016 dawns upon us, there is no doubt that Punjab is years (perhaps even decades) ahead of other provinces in overall development. Say what you may but Shahbaz Sharif has taken his province into a different league. Lahore is arguably the most developed city in Pakistan, and the gap continues to widen.

Karachi popular, Lahore and Islamabad fail to match

Yes there’s the usual (and justified criticism) about infrastructure trumping human development priorities in Punjab, but let’s hold that thought for a bit and look at what’s unfolding in Punjab at breakneck speed.

“As I drove from Karachi to Lahore,” says a Karachiite, “and crossed over into Punjab after Sukkur, it seemed to me like I had entered another country.” The gentleman narrating his impression anything but a political partisan: “The roads suddenly became better, traffic got more organised and even the surroundings seemed better.”

Slight exaggeration? Perhaps. But not by much. Compared to Lahore, Karachi is an urban decay. Potholed roads, cratered highways, unkempt sidewalks, dusty environs, garbage-strewn streets, clogged drains and a free-for-all traffic mayhem made worse by ineffectual policing.

And then the slight matter of street crime and law and order. And fear. And insecurity. Yes, it’s better now since the Rangers took charge, but that’s despite the government, not because of it.

The interior of Sindh? Balochistan? Even Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (K-P) despite some impressive reforms by the PTI government? Not a patch on Punjab (and especially the central and northern regions).

10 reasons why we love Karachi

Work is getting done. That’s what is happening in Punjab. From impressive infrastructure development to public transport systems, modern traffic management and even model-pushcarts that will have a standardised format and hygiene-checked food — all this and much more is being pushed through by the provincial government with an eye on 2018. Then there’s the clean drinking water project, as well as the Punjab IT board that is integrating technology into the arteries of the government with interesting results. There is a rush to get things done.

Bricks and mortar do define progress in Punjab. This is a progress no other province can match. But bricks and mortar do not a future make.

The Sharifs’ obsession with highways, bridges and flyovers could end up being their weakness. Till very recently, their defenders would shrug off this criticism and parrot lines about economy and foreign investment. But something changed a few months back.

In the Centre and in Punjab, there appears to be a deliberate emphasis on promoting and projecting efforts aimed at the social sectors. The prime minister is now often heard talking about the importance of education, and recently inaugurated new educational projects in the federal capital. Earlier this week, he also launched the National Health Programme, which aims at providing affordable health care to underprivileged citizens. His younger brother, meanwhile, is aggressively pursuing education and health projects and pushing for reform in these sectors.

Why this new-found focus on the social sector? Could it be the need to change the perception that the brothers only care about big, visible projects? Could it be the pressure from Imran Khan who has always prioritised social progress over bricks and mortar? Could it be a genuine desire to fix the broken health and education sectors? Or perhaps, just perhaps, they have realised that in the long run what really matters is how educated, empowered and skilled the citizens of a country are.

Why Lahore is better than Karachi today

In any case, the transformation in thinking — or perceived thinking — was long overdue. In Punjab now, massive amounts of money is being pumped into these sectors. Given the inefficiencies built into the system, there will be much financial leakage, and many impressive projects will never see the light of day beyond the files — yet there is relentless pressure on the government machinery to deliver results. Donor funds are flowing in, along with consultants, experts and advisers.

At a recent meeting, the Punjab chief minister was informed that 110,000 teachers need to be hired till 2018, which means hiring 37,000 teachers every year to meet the shortage. In addition, there currently exists a shortage of 60,000 classrooms in the province, and the construction is being funded by donors. Student retention is a major problem in Punjab (and elsewhere too) even though official figures claim that student attendance and teacher presence have improved marginally over the last year.

Ask over-eager bureaucrats in Lahore about progress in these areas and they will whip out their multi-coloured presentations. It is their job to paint rosy pictures and make their boss happy. There is much in these numbers, graphs and charts that does not bear resemblance to reality on the ground. The quality of education being taught to children in government schools is pathetic by acceptable standards. The Sharifs may have finally come around to focusing on the social sectors, but they left it really late.

But here’s the key: Punjab means business. A donor agency high-up says he has worked extensively with both the Punjab and K-P governments on education, and he feels both governments genuinely want to improve the status of education in their respective provinces. “The difference is the man on top,” he says. “Shahbaz Sharif is the driving force while Pervez Khattak is well-meaning but laidback.” He says the K-P bureaucracy runs circles around their chief minister while in Punjab it’s the other way round.

Why Lahore is the best get away for a Karachiite

Do the Sharifs skew the system in their favour? Absolutely. Does it help that one brother is the prime minister? Sure does. Do the beneficiaries of progress in Punjab care about this? Probably not.

But one thing is clear: at this rate, the progress gap between Punjab and the rest of the country will keep increasing till it may become dangerous. Dangerous? Well, that’s how some people see it. They fear a highly developed Punjab will cast dark shadows over the federation. The gap would allow incompetent politicians in other provinces to cry foul, and accuse Punjab of appropriating a disproportionate level of resources at the expense of others.

Nothing could be more unfortunate. Punjab may have taken some undue advantages but Sindh and Balochistan suffer because of the acute incompetence of their rulers. K-P has done better, yet Punjab is not to blame for most of its woes. But sadly, perceptions often trump reality, and it may yet turn out that solid progress in Punjab may in the end be held against it.

How the Brothers Sharif tackle this perceived sense of deprivation will say a lot about their political skills — and their prospects in 2018.

Published in The Express Tribune, January 3rd, 2016.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS (89)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ

After listen about lahore lahore ha lots of time . personally visit lahore but there is not such uniqueness , therefore author has to research first from the market.