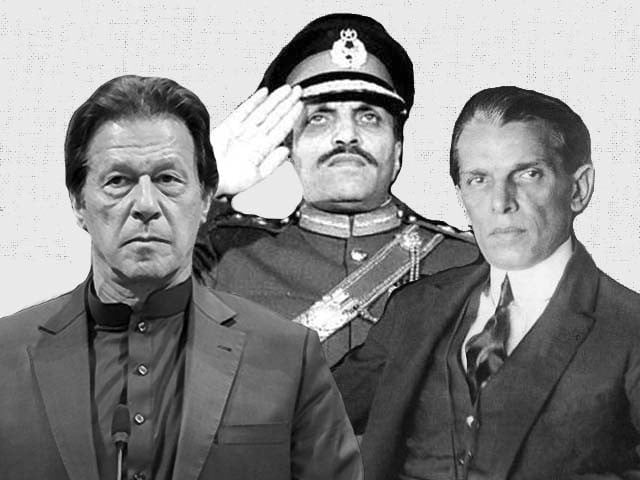

Decoding Pakistan’s perpetual cycle of history

The nature of history has been a contested topic among philosophers for centuries. Western thinkers like Georg Hegel and Karl Marx believe it to be a linear path with a beginning, middle and an end. According to them, society continuously evolves to achieve what they call the 'End of History' – a point in time with varying intellectual and material interpretations. In contrast, others, like the Muslim philosopher Ibn-e-Khaldun, postulate that history is repetitive in nature. They believe that civilisations and societies undergo the same experiences over and over again due to some inherent factors distinct to each civilisation or society itself.

While the former view has remained dominant in the age of neoliberal capitalism, the recent political turmoil in Islamabad shows that history does indeed repeat itself, at least in the case of Pakistan – a country stuck in its own perpetual cycle of history.

The beginning of this cycle can be traced back to the origin of the country itself. Like many postcolonial states, Pakistan had the odds stacked against it upon its inception in August 1947. A lacking infrastructure, meagre resources, and incoming migrants necessitated an immediate response from the nascent government under Governor-General Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

As the head of state, Jinnah was granted immense powers by the cabinet on account of his enormous leadership stature, overshadowing the remaining political leadership of the country. With a democratic polity still in the development phase, Jinnah governed through the vice-regal system which provided greater influence to provincial governors and state institutions compared to the relatively muted role of the legislature.

While this system was meant to serve as a temporary emergency measure until the formation of a stable political apparatus, tragedy struck when Jinnah succumbed to tuberculosis in September 1948 – just 13 months after Pakistan’s independence. Unlike comparable states such as India and Turkey where figures like Jawaharlal Nehru and Mustafa Kemal Ataturk respectively oversaw nation-building in the early years, Pakistan was orphaned in its infancy. This untimely loss at the state’s genesis condemned Pakistan to enter a cycle that has since repeated itself every few decades.

There are four phases that mark the completion of this cycle: promising democracy, political instability, intervening autocracy, and rebooting crisis.

The first phase is always the country’s promising embrace of a democratic system. Political consensus is built around the rules of the game, democracy is pitched as a panacea for the country’s problems, and widely-supported laws are promulgated to strengthen democratic tradition.

Unfortunately, the consensus remains surface-level – to be discarded when it becomes harmful to political interests. Politics is not devolved to the grass-root level – only the elite remain empowered. Political parties continue to be provincial, personalised and dynastic – their sustainable development is overlooked. State institutions are called on to aid the elected government whenever its political standing becomes precarious, paving way for their extra-constitutional interferences.

These neglected flaws undermine the democratic system over time. Democrats turn into demagogues as governments start abusing their power. The opposition begins agitation, conspiracy theories emerge, political polarisation increases, and the law and order situation deteriorates. What had once been a promising democracy ends up in a state of political instability. The military intervenes and imposes martial law on the pretext of ensuring stability and maintaining law and order. Once the autocratic regime quells the turmoil, its dictator designates himself as president, claiming it to be a temporary measure until democracy is fully restored. Momentary stability coupled with incoming foreign aid paves way for economic growth. The progress emboldens the dictator to seek legitimacy from the public through democratic means, ending up as the winner amid allegations of electoral fraud.

The cycle comes to an end with a crisis that creates a vacuum at the top, subsequently filled by a democratically-elected leader and beginning the entire cycle once again.

The first cycle in Pakistan’s history started in 1948 with Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan taking up the leadership role left vacant by Jinnah’s departure and ensuring the adoption of the Objectives Resolution to set the country on the path of democracy. In the period following Liaquat’s assassination, the democratic system turned highly volatile, and the country remained politically unstable. Pakistan had seven different prime ministers between 1951 and 1958. General Ayub Khan’s military coup ended this volatility by introducing an autocratic system, only coming to an end with a crisis: the dismemberment of Pakistan in 1971.

As democracy resumed under Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, a second cycle began. The promulgation of the Constitution of Pakistan in 1973 raised many hopes regarding the future of democracy in the country, only to be let down by the intense confrontation between Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and the Pakistan National Alliance – a coalition of nine political parties. The turmoil caused by the face-off settled down when General Ziaul Haq imposed martial law and returned Pakistan back to another decade of autocracy. His regime came to an end with his own death in an airplane crash in 1988.

The cycle began a third time with the election of Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto – the first female head of government in the Muslim world. Political instability soon followed as Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif alternately switched premiership tenures with neither of them completing their full five-year term. The rotation ended with yet another military intervention – this time with General Pervez Musharraf imposing the third martial law in the country’s history. Unlike previous cycles, General Musharraf’s exit was relatively peaceful, coming through a resignation in 2008 as a result of an impeachment proceeding initiated against him.

The removal of a dictator through democratic means created hope that perhaps Pakistan had finally exited its cycle of history.

In the previous decade and a half, Pakistan has made great strides to preserve its democracy. The 18th Amendment revived Jinnah’s federalist vision. For the first time in Pakistan’s history, a democratically-elected government completed its full five-year term, peacefully transferring power to its successor. The emergence of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) as a formidable political force upended the political duopoly that existed under the traditional two-party system.

While these have been welcome changes, they remain insufficient for the disruption of Pakistan’s cycle. Politics is still dominated by elitist interests. Political parties still operate around individuals and dynasties. State institutions are still expected to act as arbitrators between political actors. Such deep-seated flaws in Pakistan’s democratic system have ensured that the country keeps repeating the mistakes of its past to this very day.

In the wider context of the country’s history, the recent political turmoil – leading to and resulting from former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s exit – is not a unique occurrence. It merely represents the country’s transition from one phase of the cycle to another.

As in the past, this phase of political instability has already witnessed the creation of a grand multi-party alliance, an incomplete government tenure, widespread conspiracy theories, and an emerging narrative against state institutions. The political polarisation resulting from populist rhetoric is also not a new phenomenon but one that has manifested itself in the same phase of the previous cycles.

Pakistan keeps repeating its cycle of history as a result of fundamental flaws in the country’s democratic system, neglected for decades by those who benefit from them. The extractive nature of Pakistan’s political institutions means that progress made by the country will remain compromised, to be reset with each and every cycle.

It is high time that Pakistan addresses the issues that have set its political system up to fail. The cycle must end. And the first step toward ending the cycle is to acknowledge that a cycle exists.

COMMENTS (4)

What a comprehensive review I really liked how you identified the phases of Pakistan s politics. It s high time to break out of this cycle.

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ