US Secretary of State Antony Blinken testified before Congress earlier this week that his countries’ interests and Pakistan’s in Afghanistan sometimes “conflict”. He described Islamabad’s policy as one of “hedging” wherein he implied that it plays all sides in order to safeguard its interests in any scenario. America’s top diplomat then told lawmakers that “we’re going to be looking at in the days, and weeks ahead - the role that Pakistan has played over the last 20 years but also the role we would want to see it play in the coming years and what it will take for it to do that.” This prompted concern among some observers that Pakistani-American relations might once again become very complicated.

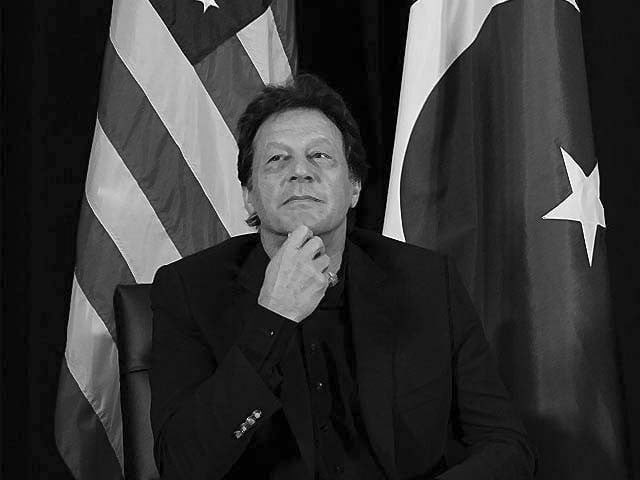

As it presently stands, their ties are pragmatic but can’t be described as anything more. US President Joe Biden still hasn’t called Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan even though Russian President Putin has already spoken to him twice in less than a month’s time. Islamabad was integral to bringing the Taliban to the table and facilitating the February 2020 peace deal that ultimately resulted in the US’ withdrawal from Afghanistan last month. The South Asian state also played a key role in assisting that panicked evacuation. Additionally, it continues to exert positive influence on the Taliban, which countries such as Russia still officially considers to be terrorists despite the Kremlin pragmatically engaging with them in the interests of peace and security.

For as “politically incorrect” as it may be to say, Blinken was correct in his assessment of Pakistani-American differences, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing nor anything to automatically be concerned about. It’s natural that no two countries’ interests will ever perfectly align on all matters, especially concerning a 20-year-long war waged by one of them whose effects spilled over the border into the other. Furthermore, there’s nothing wrong with any country “hedging”/”balancing” since this is normal in the emerging Multipolar World Order. Pakistan still cooperated with the US on high-level anti-terrorist matters related to Al Qaeda but understandably didn’t want to risk worsening domestic turmoil along its frontier by playing the role of policeman against the Taliban.

After all, Pakistan never regarded the Taliban as terrorists, unlike the US. Islamabad knew very well that peaceful cross-border ties between the two countries’ Pashtun communities couldn’t be disrupted without destabilizing both of them. Pakistan’s political position towards Afghanistan was ultimately proven right after even the US itself began to talk with the group and incorporate it into the war-torn country’s political process as a legitimate stakeholder. In hindsight, Pakistan’s “hedging”/”balancing” actually contributed to regional peace, it didn’t detract from it. The “conflict” of interests between it and America in Afghanistan always remained manageable for the most part and eventually led to a convergence of interests during the final years of the war.

The only reason why those prior differences are being publicly discussed right now is due to American lawmakers’ disgust at how chaotic their country’s withdrawal from Afghanistan was. They’re looking for someone to scapegoat for the entire mess that former US President George W. Bush Jr. got them into nearly two decades ago, and Pakistan is always a convenient target to pin the blame on in spite of Islamabad helping them and their allies during the evacuation. US officials are now wondering what the future of their relations with Pakistan will be after the Taliban once again became Afghanistan’s de facto leaders, but it’s unclear whether ties will worsen.

Differences still exist between the two though they’re of a different form than before in light of the changed circumstances. Both countries hope that the Taliban will respect minority and women’s rights, though the US is stricter about enforcing compliance with its expectations than Pakistan is. America froze Afghanistan’s assets in the country and had the two international financial institutions under its influence, the IMF and World Bank, suspend the country’s loan programs in order to pressure it. Pakistan, on the other hand, believes that all efforts should be made to immediately support Afghanistan’s socio-economic reconstruction without political preconditions in order to stave off an impending humanitarian crisis there that could destabilize the region.

Apart from these few differences, which are nevertheless still significant considering their strategic impact on Afghanistan’s stability, there’s also hope that Pakistani-American relations will remain pragmatic even if they don’t improve and never return to the excellent level that they used to be at many years ago. The US unveiled a “New Quad” in late July comprised of itself, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan, the latter three of which agreed in February to construct a trilateral railway (PAKAFUZ) between them. The State Department’s official press release also confirmed that this new structure is explicitly predicated on “enhancing regional connectivity”, which aligns with the geo-economic goals from the US’ “Strategy For Central Asia 2019-2025”.

Their complementary geo-economic interests in post-war Afghanistan suggest that America won’t do too much to proverbially rock the boat with Pakistan despite the partisan-populist urging of some lawmakers. The only variable of relevance that could offset this prediction is if the US’ permanent military, intelligence, and diplomatic bureaucracies (“deep state”) decide to throw their weigh much more towards India at Pakistan’s perceived expense after next week’s first-ever in-person Quad Summit. In particular, the US might give a wink and a nod to joint Indo-Iranian efforts to provoke trouble for the Taliban in Afghanistan as well as double down on its de facto military pivot towards India that’s unofficially aimed against China.

The “New Quad” and PAKAFUZ are important for the US’ post-war regional objectives but their practical implementation could be indefinitely delayed if this serves the purpose of undermining Russia’s connectivity interests vis-a-vis fulfilling its centuries-long strategic goal of reaching the Indian Ocean through that railway. That possible scenario could only realistically transpire if Afghanistan is further destabilized through the external exacerbation of its economic crisis via the US’ earlier mentioned weaponisation of financial instruments and if joint Indo-Iranian efforts succeed in provoking political or potentially even military trouble for the Taliban. In that event, China’s interests there – which are related to the possible pioneering of a “Persian Corridor” to Iran through Tajikistan and Afghanistan as well as its access to minerals – would also be sabotaged.

Put another way, the future of Pakistani-American relations and especially those countries’ interactions in Afghanistan will be influenced by the US’ broader strategic calculations related to its potential employment of India as a proxy for destabilizing that third country. This course of action could be undertaken in an attempt to undermine the interests of Washington’s Russo-Sino rivals there, though it’s unclear whether this plot would succeed. A lot would also depend on Iran’s participation in this scheme, as curious as it may be to imagine the Islamic Republic having some shared interests there with the same country that it infamously regards as “The Great Satan” even if there’s no direct coordination between them in this respect. It should go without saying that this might not succeed, in which case the US would just resort to relying on the “New Quad” and PAKAFUZ.

Strategically speaking, the US “deep state” might still feel more comfortable formulating its relevant policies on the basis of geopolitics as epitomized by the above proxy-driven divide-and-rule destabilization scenario as opposed to the emerging trend of mutually beneficial geo-economics manifested by the “New Quad” and PAKAFUZ. The very fact that both possibilities are presently on the table speaks to the fact that the US also “hedges/balances” in pursuit of its interests, though in a different way than Pakistan does. Nevertheless, America’s geopolitical stratagem would be advanced at Pakistan’s expense, in which case bilateral relations would definitely deteriorate, but nothing has been decided upon for the time being and that’s why Blinken only vaguely talked about reassessing relations with Pakistan – and that too only because he was asked.

The most effective way for Pakistan to ensure its interests in this complicated context is to rally international support for Afghanistan’s post-war socio-economic reconstruction so as to offset its impending humanitarian crisis that poses such a threat to regional stability. Islamabad should also politically back the Taliban’s efforts to counter externally provoked plots against its de facto rule. If America decides to advance its geopolitical interests in Afghanistan, then this will pose a threat to Pakistan’s interests, but the failure of the former’s possible attempts would result in it advancing its geo-economic backup plan in response which perfectly aligns with Pakistan’s interests.

It would of course be best for the US to remain committed to the geo-economic goals represented by the “New Quad” and PAKAFUZ instead of recklessly playing geopolitical games, but it can’t be guaranteed that the country’s “deep state” learned its lesson from Afghanistan just yet. Some influential forces within it might be tempted to take revenge on the Taliban, both to “save face” before the American public as well as complicate matters for China and Russia, which could push them towards the geopolitical scenario that Pakistan must do its utmost to thwart within all responsible means at its disposal. Pakistan and the US will therefore continue “hedging”/”balancing” against one another in Afghanistan as long as America pursues zero-sum geopolitical interests, which is why it’s so important for the US to pursue mutually beneficial geo-economic ones instead.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ