In November 1878, Britain, for a second time in 40 years, declared war on Afghanistan. A year later, Britain decided to dismember Afghanistan once and for all. As per the plan, Herat and Seistan (present-day Nimruz province and its surroundings) would be handed over to Persia, and Qandahar would be presented to a Durrani sardar under British suzerainty. The fate of the remainder of Afghanistan was, however, unclear. The British Cabinet confirmed these measures in December 1879.[i] Britain, thus, wanted to neutralise any and all threats emanating from Russia, through Afghanistan, to its Indian empire.

Britain assumed direct control of Kabul in October 1879, when the Afghan ruler Yaqub Khan (Ayub Khan’s elder brother) abdicated declaring ‘he would rather be a grass-cutter in the English camp than ruler of Afghanistan.’[ii] After eight months of direct occupation, in June 1880 Britain established contact with Abdur Rahman (Yaqub Khan’s and Ayub Khan’s cousin) to see if Kabul could be handed over to him. While negotiations between Abdur Rahman and the British were in progress, news reached the latter in Qandahar that the Herat governor Ayub Khan was on his way to Ghazni from Herat with thousands of troops and would pass through Qandahar.

Since the negotiations with Persia regarding the transfer of Herat and Seistan had not made much progress, in May 1880 the British confirmed Sardar Mehrdil Khan’s son[iii] Sardar Sher Ali Khan (not to be mistaken for his half cousin, former Afghan ruler Amir Sher Ali Khan, who had died in February 1879 in Mazar-e-Sharif) as governor of Qandahar. At the confirmation ceremony, Sher Ali wished for an opportunity to use his sword in defense of the British government—a wish that would soon be granted.

In order to forestall a general uprising around Qandahar, the British decided to intercept Ayub Khan before he reached Qandahar. Around this time, Sher Ali’s own troops were busy collecting taxes in Zamindawar. As Ayub Khan approached the area, Sher Ali’s troops deserted en masse and joined Ayub Khan. The troop desertion deprived Sher Ali of the opportunity to use his sword in defense of the British government and the British of a vital source of local support.

While Ayub Khan was about to confront the British, Abdur Rahman was wrapping up his correspondence with them. The British found Abdur Rahman compliant enough to ascend the throne of Kabul in July 1880. In his correspondence with Abdur Rahman, the British agent in Kabul Mr. Griffin clearly stated that Qandahar would not be part of Abdur Rahman’s dominions, and that the British would be in charge of his foreign affairs. Abdur Rahman did not register any objections to either of these diktats.

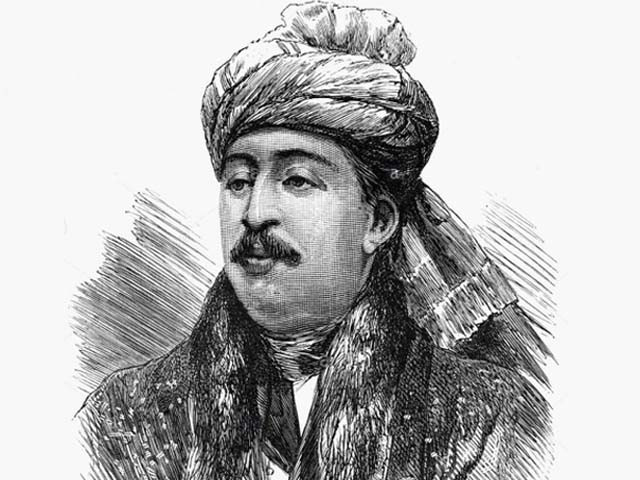

The Afghan and British troops, by coincidence, came face to face near Maiwand, midway between Qandahar and Girishk. In the ensuing battle—known as the Battle of Maiwand—on July 27, 1880 the Afghans under Ayub Khan defeated the British. The Afghan victory at Maiwand was strategically significant for Afghanistan. First, it was the first and last pitched battle in an open field between regular Afghan and British troops which ended in Afghan victory. Second, the Afghan victory saved Afghanistan from being dismembered by Britain, and saved Qandahar from a permanent British occupation. The defeat at Maiwand would compel the British to withdraw from Qandahar in 1881.

The Afghan victory also generated ‘excitement’ amongst the Pashtun tribes along the Indo-Afghan frontier, and the British sensed ‘uneasiness’ throughout India. That being said, of the 934 dead British soldiers at Maiwand, 624 were so-called ‘native’ (mainly Pashtun; Punjabi, both Muslim and Sikh; and Gurkha) and only 310 were European.[iv] It was strange to see the ‘natives’ fighting for a foreign power, who had subjugated and colonised them, against their Afghan neighbors, who were fighting for their freedom. This was an unfortunate pattern repeated in all Anglo-Afghan wars, and a classic example of the brown man shouldering his white master’s burden.

After the battle, the Afghans buried the dead British soldiers and erected a monument, a pillar of sun-dried bricks, in their honor and memory.[v] This generous gesture by the Afghans under Ayub Khan usually goes unnoticed by the British, whose colonial officials and soldiers left no stone unturned to portray the Afghans as a ‘savage’ and ‘wild’ people. After the Battle of Maiwand, Ayub Khan advanced on Qandahar, but was unable to dislodge the British from it. In a subsequent battle on September 1, 1880 in present day Arghandab district, General Roberts defeated Ayub Khan, who withdrew to Herat.

Despite Roberts’s victory at Qandahar, the British position in southern Afghanistan was still untenable. The consequences of the defeat at Maiwand, which were about to play a significant role in changing the British strategic calculations regarding Qandahar, were dawning on British policymakers. Had the British hold on Qandahar not been challenged and shaken by Ayub Khan, Qandahar would slowly have become a part of the British occupied subcontinent.

Considering the defeat at Maiwand and Sher Ali’s sheer incompetence and lack of local support, the British now had two choices: withdrawal from Qandahar or a permanent, direct occupation of it. The latter choice, in addition to opposition from Afghan tribes, ran the risk of provoking Russia to move closer to Afghanistan’s northern borders.

Therefore, after heated discussions in Britain, in March 1881 the House of Commons decided to withdraw British troops from Qandahar. The British, however, continued to occupy the districts of Pishin and Sibi. Before the British withdrawal, in November 1880 Sher Ali decided to leave Qandahar and settle with his family in Karachi.[vi]

After the British withdrawal, their handpicked ruler of Kabul Amir Abdur Rahman occupied both Qandahar and Herat in 1881. Ayub Khan took refuge in Persia, where he lived until 1888. The British in 1888 arranged for Ayub Khan’s transfer from Persia to India, where he spent the rest of his life. Upon arrival in Karachi, Ayub Khan was received by the same Sher Ali who had left Qandahar permanently and settled in Karachi nearly a decade ago.[vii] From Karachi, Ayub proceeded to Punjab, to settle in a life of exile, where died in 1914.

Ayub Khan, along with his mother and other family members, was buried in Peshawar’s Durrani cemetery. The cemetery is located close to Wazir Bagh, a royal Durrani garden built by the Afghan ruler Shah Mahmud Durrani’s wazir Fateh Khan Barakzai in the 1810s, when Peshawar served as the winter seat of the Durrani rulers of Afghanistan. In appreciation of Ayub Khan’s services, the Afghan government renovated his grave about 15 years ago. However, it was reported last year that the marble pieces from Ayub Khan’s grave had been stolen.

After partition, several of Ayub Khan’s descendants have served in various capacities in Pakistan. For instance, two of Ayub Khan’s grandsons Hissamuddin Mahmud and Ismail Khan have served as General Officers Commanding (GOCs) in the Pakistan Army. It’s interesting that both the leading Afghan characters of the Battle of Maiwand (Ayub Khan and Sher Ali) settled in northern India, which after partition became part of Pakistan. The presence of their descendants, with Pakistani citizenship and Afghan ancestry, in Pakistan is yet another indication of close people-to-people relations between Afghans and Pakistanis.

[i] Sir William K. Fraser-Tytler, Afghanistan: A Study of Political Development in Central Asia, P. 148.

[ii] Frederick Roberts, Forty-one years in India: From Subaltern to Commander-In-Chief, P. 414.

[iii] Arnold Fletcher, Afghanistan: Highway of Conquest, P. 136.

[iv] Frederick Roberts, Forty-one years in India: From Subaltern to Commander-In-Chief, PP. 470-71.

[v] Arnold J. Toynbee, Between Oxus and Jumna, P. 65.

[vi] Sir William K. Fraser-Tytler, Afghanistan: A Study of Political Development in Central Asia, P. 154.

[vii] Sardar Abdul Kadir Effendi, Royals and Royal Mendicant: A Tragedy of the Afghan History, 1791-1949,

P. 249. The author is Ayub Khan’s eldest son. Shortly after partition, Effendi’s book was published by Lion Press

in Lahore. In it, Effendi provides an account of his family’s involvement (mostly as the Afghan ruling elite) from

Sardar Painda Khan down to his own father Sardar Ayub Khan.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ