“Us Pakistani liberals have long defended India, so much so that it has almost become a reflex, but honestly an India that has sunk into such depths just cannot be defended: dishonest journalism, joke of a secularism, knee-jerk Hindutva reactionism.”

Us Pakistani liberals have long defended India, so much so that it has almost become a reflex, but honestly an India that has sunk into such depths just cannot be defended: dishonest journalism, joke of a secularism, knee-jerk Hindutva reactionism. https://t.co/6pyrZW6yMP

— Sabahat Zakariya (@sabizak) September 4, 2019

These words are so reflective of the way monumental and rapid changes in India are forcing Pakistani liberals to change their assessment and opinion of the country. A few years ago, we liberals used to be at the forefront of defending India as it often meant denouncing the jingoistic attitude of ultranationalists. Personally, I have gone to the extent of calling myself a Pakistani Indian.

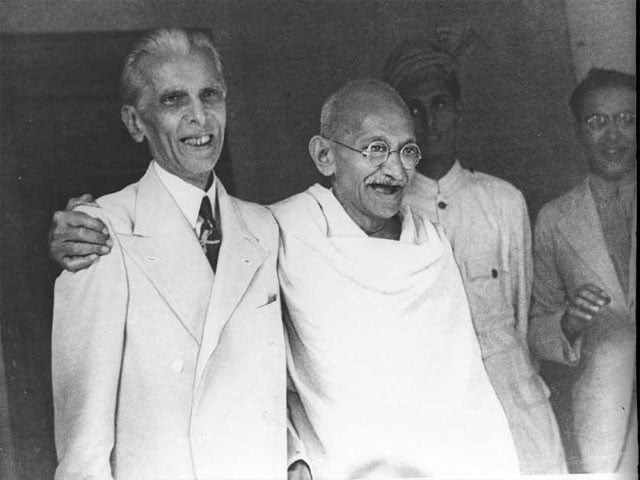

Liberals have also had an uneasy relationship with the Two Nation Theory (TNT). Most of us admired Mohammad Ali Jinnah for his secular and liberal credentials but also had a skeptical attitude towards the theory. The uneasiness was genuine as it emanated out of liberal concerns about communal harmony and the theory, since it presented a case for a separate homeland for Muslims, was apparently based on communalism. Hence, especially because Jinnah was personally a liberal and secular, started his political career with the Congress and was known as the Ambassador of Hindu Muslim Unity, his eventual advocacy of the two-nation theory was intriguing.

It was this paradox that a person as liberal and secular as Jinnah ended up becoming a proponent of the TNT which interested me deeply. One of the academic pursuits of my life, as I changed my career from banking to academia, then became,

“Was Jinnah right?"

For the detractors of the TNT, the most obvious example of its “failure” is the creation of Bangladesh. They claim that since East Pakistan decided to separate, the theory was proved wrong as Islamic identity — the idea upon which Pakistan was based — was unable to contain the ethnonationalist aspirations of the Bengalis. As I wrote around three years ago, this criterion is incorrect. The creation of Bangladesh has more to do with the over-centralisation by West Pakistan and their negation of Bengali culture and ethos. I wrote,

“The reason why Bangladesh came into being is less to do with the fallacy of the TNT and more with how West Pakistan treated East Pakistanis. The TNT would have been discarded if Bengalis had opted to join India in 1971”.

The real test implication for the TNT cannot be whether Pakistan stays intact as a territorial entity or breaks up due to ethnic tensions. This is because the theory was not framed in terms of ethnic versus Islamic identity. It did not claim that Islamic identity alone is enough for an ethnically diverse state to survive. Any state, no matter how it came into being, has to build civic nationalism in such a way that ethnic differences are harmoniously accommodated. If Pakistan failed to so in the case of East Pakistan, then it’s the failure of its model of civic nationalism and not of the TNT.

The actual test for the theory is the way Muslims are treated in India. The original argument postulated by the TNT was that in a united India, due to numerical disadvantage, Muslims would be discriminated against and, therefore, they need a separate state. The idea of a separate state was intertwined with the concept of a nation. The argument was not merely that Muslims were a separate nation because you can have 10 nations within a country.

Eventually, the theory had to be accepted or rejected based on the way India, including its government and its population, treated Muslims. And since India defined itself secular as opposed to a religious state, the TNT was eventually judged against that claim also. To be honest and fair, India, at least at the state level, did try to do that. It declared itself secular constitutionally, and as long as the Congress was in power, tried to do its part. Maybe even overdid it as the Shah Bano case reveals.

But since the mid 1980s, India has adopted a different character. The current party in power rose in popularity by fanning anti-Muslim sentiments and championing the controversial Ram Mandir issue. However, the rise of the party still did not prove that the TNT was correct. Many countries have such parties but they remain on the fringes just like the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) tried to under Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Vajpayee's shock defeat in 2004, however, changed everything. In 2014, when Narendra Modi, a thoroughly controversial person, became a nominee for the post of the prime minister, it was becoming clear which way India was heading. Despite the fact that BJP had so many choices, it decided to go with Modi, by far the most conservative choice available to the party.

Back then, any concerns about Modi’s troublesome history were dismissed by even supposedly moderate people by over emphasising the 'Gujrat Model' of development. The fact that Muslims had serious reservations was simply brushed away. Modi’s tenure from 2014 to 2019 started to confirm the worst fears of Muslims as now the sentiment on the fringes started to become mainstream. Initially, many Indians denied it but when the evidence started to become too hard to deny, they started to justify it. State election campaigns in places like Uttar Pradesh were brazenly communal and, after the victory, Yogi Adiyanath, a person even more controversial than Modi, was appointed, once again completely disregarding Muslim concerns.

When the economic performance under Modi's government started to slow down due to recession and its ill-fated attempt of demonetisation, BJP once again intensified its communal rhetoric. The 2019 election campaign was a combination of the explicit communal rhetoric and whipping war hysteria against Pakistan. Despite its mixed record of economic performance, BJP won an even greater majority. Kapil Komirdidi, famous journalist and author, wrote after journeying India before the elections,

“Wherever I have travelled, the refrain from Hindu voters, with very few exceptions, has been identical: Modi has failed us, yes, but he has at least put Muslims in their place.”

These words perhaps best reflected the prevailing mass sentiment in India on the eve of elections. Whatever little doubts I had remaining were completely eliminated by India’s fateful decision of the revocation of Article 370. Kashmir is the only Muslim majority state, making it a litmus test for Indian secularism and also for the protection of its Muslim minority. The Indian part of Kashmir had arguably acceded to India through Article 370 which gave it a special status. By revoking it in a thoroughly controversial manner and subsequently increasing state oppression, the BJP government has shown that it cares little for the consequences. Worse, a large majority of Indians are cheering at the decision, completely dismissive about the reports of atrocities committed by their security forces.

What happened in Indian-occupied Kashmir has given us a blunt indication as to what would have happened if partition had not taken place. India is now secular in name only, which I am sure will also change in the near future, as there is a serious risk of the constitution being rewritten making the polity a Hindu Rashtra. Moreover, the very social fabric of India has also changed making it very difficult for Muslims and other minorities to live in. As Komirdidi points out,

“The very narrative of the republic — what is considered Kosher — has been rewritten and reclamation will be difficult. There was a time in this country where to be a Hindu nationalist, or a RSS member, was stigmatised. Now there is stigma attached to being secular. If you are a secularist, you are an apologist for the crimes of the Muslim invaders and the trauma of partition.”

So yes, Jinnah was right. History has given its verdict. For me, the journey from a skeptic of the TNT to its believer is complete. Thank you, Jinnah.

[poll id="793"]

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ