Though not mutually exclusive, maintaining its (historically love-hate) relationship with US is a mammoth task if it is to yield the benefits of China’s development and investment initiatives

Caught in the middle: Pakistan’s position in the US-China power shift

Can Pakistan ride the ever-turbulent wave of this great power rivalry, or is it playing dangerously close to the fire?

China’s rise has triggered a myriad of debates among political and academic commentators alike. Will it be peaceful and rely solely on America's decline? Or will the changing structure of the international arena inevitably be riddled with war and violence? As the aforementioned thoughts become the subject of repeated discussions, another problem closer to home becomes more and more pressing: can Pakistan ride the ever-turbulent wave of great power rivalry, or is it playing dangerously close to the fire?

Developing trends in regional governance suggest that although American hegemony endures on the international scale, it is undoubtedly being subverted, as China’s global influence continues to expand. Although it is accepted – at least for the time being – that China lacks the military and economic resources to overtake the US as the world hegemon or transform the liberal international order, it is instead using its regional political influence to campaign for long-term, indirect changes to the international arena.

The decline in US’s international reputation can in large part be attributed to the George Bush administration’s failed global war on terror; the legacies of which have been lingering for nearly 18 years. Despite Donald Trump’s plans to withdraw troops from Afghanistan, his presidency marked a surge in drone strikes and even the granting of greater military autonomy in the region. Yet the Afghan Taliban controls even more territory since 2014, and tentative steps towards negotiations with the group continue to wax and wane.

The costs of this long war against the Taliban, (borne predominantly by Afghanistan and Pakistan) serve to remind the world of US’s doomed strategies of pre-emptive warfare and endless military presence. More broadly, the war on terror has signified a diminished faith in US’ brand of foreign policy, and in its image as an arbiter of global peace and stability – instead, leaving space for countries like China to propose their alternate and more conservative vision of international governance.

The power that China currently wields both regionally and beyond is considered by many to be part of its ongoing strategy to balance the scales against the US. China has overtaken both Russia and Japan in terms of regional economic strength. And since Trump’s reversal of the famed ‘pivot’ to Asia, China’s ability to dominate the continent in trade, and in fact pull US’s long-term allies from the Asia Pacific such as Indonesia and the Philippines further into the fold, grows with each new trade deal, loan or infrastructure project.

On the geostrategic front, China’s increasingly turbulent relations with surrounding states have given the West cause for concern. The projection of Chinese military power against its significantly weaker neighbours over the issue of the South China Sea, signals that China’s rise will be more violent than is usually assumed. Her growing naval presence and island-building activities around the Paracel and Spratly islands demonstrate efforts to ward off the weaker nations who have claim to the territories. Additionally, though the US has taken an officially neutral stance in the South China Sea conflict, creeping militarisation of the area justified by freedom of navigation, could point towards military conflict in the future.

Enter Pakistan…

By now it has become clear that China intends to challenge or at least curb western influence in the region, more so with the support of its allies in East and South Asia.

Enter Pakistan, a country which faces a unique set of challenges based on its historic ties with the US, as well as the heightened fervour with which it seeks to become more developed and economically stable. In order to navigate these shifting political landscapes, Pakistan must make some hard choices. Though not mutually exclusive, maintaining its (historically love-hate) relationship with the US is a mammoth task if it is to yield the benefits of China’s development and investment initiatives – which many have quietly begun to doubt.

It is important to view this issue as a nuanced, rather than a black and white one. Pakistan’s military relationship with both countries has been maintained for decades, as a means of serving different purposes: with China, Pakistan has sought to counter-balance India, and with the US, Pakistan has been a strategic security partner especially since 9/11. Yet since China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the China-Pakistan relationship has turned up a notch and the US no longer wishes to watch quietly from the side-lines.

Despite once supporting aspects of China’s infrastructure programmes in the country (for example, in the construction of power plants that comprise of American-designed and built turbines), the US has quickly caught on to the counterproductive effects that CPEC is having on Pakistan’s debt – not withstanding its inability to alleviate balance of payment crises without the help of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or more recently, countries like Saudi Arabia in the form of loans and foreign-currency support.

Yet the effect of Trump’s increasingly punitive stance against Pakistan (through suspending military aid among other things), appear only to be waning. Pakistan continues to enjoy its leverage against the US vis-a-vis Afghanistan, but this time with backing from a powerful and deep-pocketed security partner next door. A line up of One Belt One Road (OBOR) projects, along with the building of a port at the strategic location of Gwadar, will not only bolster China’s access to natural resources, but also its power in surveillance technology and at sea. The advantages for China are therefore overwhelming. But if one day Pakistan’s relations with the US become irrevocably damaged, one cannot help but question what a partnership with China will mean for its long-term sovereignty and security.

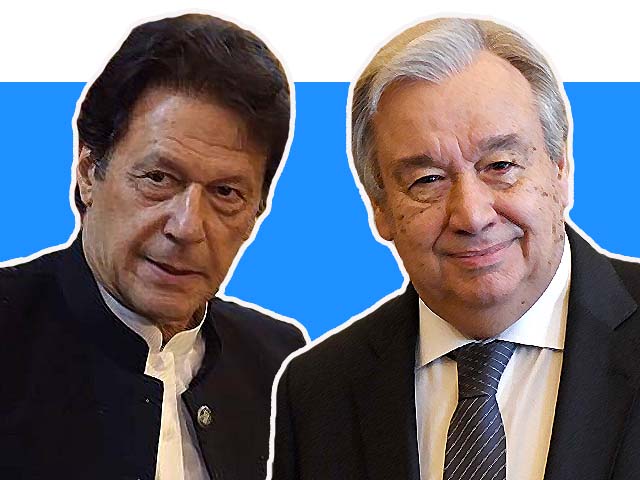

When combined with Pakistan’s preference for China as a military weapons supplier, and the emotive rhetoric of Imran Khan’s government against being treated as a ‘hired gun’ by the US, the issue of CPEC can no longer be viewed as a regional partnership between two countries. Instead, CPEC and China’s wider OBOR initiative which spans across three continents, chiefly symbolise its efforts to undercut US influence and power on its doorstep and beyond. The 2018 Pakistan General Elections marked a new dawn in Pakistan’s political and economic trajectory, yet they also signified a trend towards further entanglement in a potentially violent power struggle between two major powers, out of which Pakistan could inevitably become the collateral.

COMMENTS (1)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ