The lost world of Ishtiaq Ahmed

Despite limited scope and puritanical leanings, his stories grabbed attention of a whole generation of young readers

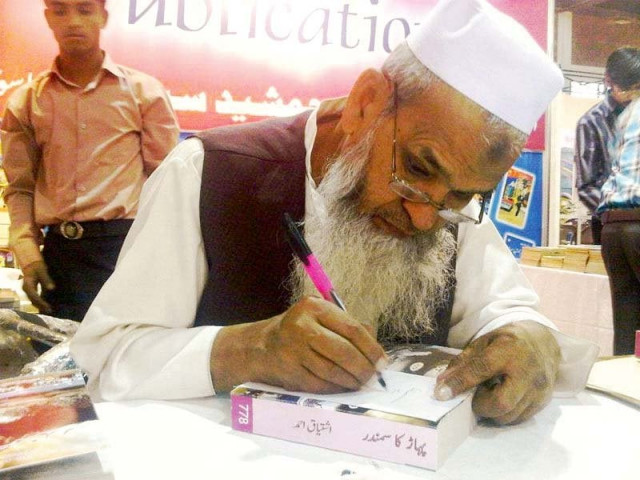

Ahmed was a ‘literary progeny’ of Urdu’s foremost detective and suspense fiction writer Ibn-e-Safi. PHOTO: FILE

Urdu’s most influential critic, Muhammad Hasan Askari, had once proclaimed that Urdu literature is dying. Like all his ideas, which usually sparked heated debates, this proclamation also found its enthusiastic supporters and opponents in the literary circles across the sub-continent.

Some 60 years on, I cannot say with confidence whether Askari was right or wrong in his judgement. However, what people should not doubt now is that Urdu literature for children has formally come to an end — at least for now — with the passing of its most prominent, most prolific, most committed and apparently the last dedicated writer, Ishtiaq Ahmed.

Ishtiaq Ahmed, a ‘literary progeny’ of Urdu’s foremost detective and suspense fiction writer Ibn-e-Safi, was surely not as gifted as his predecessor. But unlike a dozen others, who, under the influence of Safi, turned to detective fiction for adults while also burrowing his characters and settings [and sometimes even the scheme of his nom de plume], Ahmed was among the first to write for children.

Children books author Ishtiaq Ahmed passes away

And when he wrote, he created a world of his own. It was not as grand and colourful as the world of Ibn-e-Safi. However, in spite of its limited scope and puritanical leanings, Ahmed’s stories presented a picture that grabbed the attention of a whole generation of young readers.

Thirty odd years back it was still the age of the printed word and the characters of Ishtiaq Ahmed were household names. Every other child knew that Inspector Jamshed had got the better of Inspector Kamran Mirza in their first accidental encounter; that Jamshed’s son, Mehmood, wore special shoes with a knife hidden in one of his heels; that Khan Rehman owned diamond mines in Africa and that Ms Jamshed could tell from ring of the bell who was at the door.

This pure little world was essentially stable and prosperous. Its crimes were surrounded in the thick air of mystery and its characters were valiant, skilled, a little garrulous and carefree. In this world international conspiracies were hatched twice a year but well-intentioned people were still at the helm. Here the protagonists neither aged nor died while they also had time, resources and freedom to fly to far-off exotic places — at the drop of a hat — to unravel some secret.

However, Ishtiaq Ahmed’s world was also powerfully aligned with the ideological state of General Ziaul Haq. It was a world without any political chaos and discordant voices — a world where the protagonists received orders directly from the all-powerful president of the country — to safeguard the interest of the country and ummah.

Renowned novelist Ishtiaq Ahmed passes away at 74

So was it the reason why charm of Ishtiaq Ahmed was on the wane soon after the political change and rise of democracy in the country? One might postulate that he started to relegate to the background with the beginning of 1990 as new realities were becoming more and more incompatible with his ideal world.

Whatever might be the cause of Ahmed’s apparent downturn, the generation of 1970s and early 1980s would sometimes recall the wonders and joys of the world created by him. But what they seemed to have become oblivious of was the fact that their favourite childhood characters were still alive somewhere, still busy in solving enigmas and thwarting designs of cunning enemies.

This last warrior, this Hiroo Onado of Urdu’s detective fiction, had lost most of his ground but not his heart. He was constantly writing for the audience that had left with him. Was it obstinacy or a writer’s existential need to express himself [or both] that caused him to pile up books after books until their number exceeded the figure of 1,100?

Memorial: Friends, family remember Agha Afzaal Hussain

Or was it because of his love for children? In one of his last conversations at the Karachi International Book Fair last week, Ahmed had told an interviewer he could never disappoint a child. It was probably a sense of duty towards these children that he kept spinning yarns. For as long as someone is listening, the story must go on!

Published in The Express Tribune, November 22nd, 2015.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ