Adventures and history

The historical novel is entrenched in the modern consciousness.

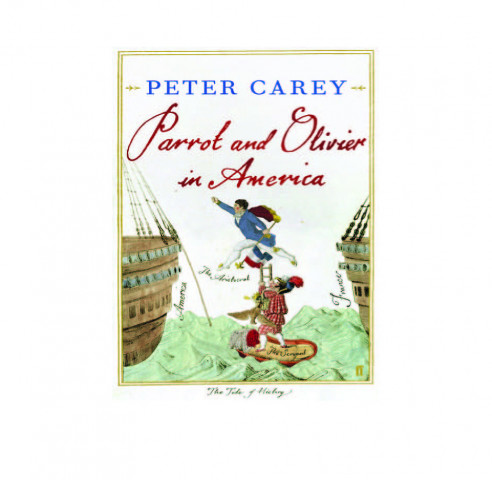

Peter Carey’s latest novel Parrot and Olivier in America is a fun ride to the early nineteenth century metamorphosis of the old structure into the new. The character of Olivier de Garmont is based upon the classical-liberal French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville who travelled to America in 1831 and wrote Democracy in America, a classical masterpiece on the democratic system of America. However, the novel is not about Tocqueville. Unlike Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, Peter Carey’s narrative is not a commentary about contemporary political issues in the guise of the past. His novel is a rendition of the past as an uncanny “distant mirror” of humanity itself.

History for Carey is “unreliable”. He presents its amphibious nature in a vivid tale of adventures of Parrot and Olivier. Olivier is a troubled aristocrat from an anti-revolution family, “living in a constant state of contradiction and confusion” in post-Napoleonic France. Being a confused liberal aristocrat, he is trusted by neither side and is forced to flee to America. Tocqueville went to America with Beaumont, a fellow aristocrat, who is replaced by Parrot, a Dickensian tragic survivor from the lower rung of the social ladder. He is employed to spy on Olivier by his mother in the novel. Initially, both characters are repelled by each other but when they reach America their companionship transforms into a peculiar friendship. Throughout the narrative, both characters are addressed by various names and titles to highlight the relativity inherent in identity. Furthermore, the writer subverts the structure of power politics by placing Parrot first in the title of the book and dividing the narrative voice equally between the two.

“I might be safe from the so-called July Revolution, but I was not safe from love”, says Olivier when he falls in love with an American beauty. Parrot’s beloved, on the other hand is a passionate artist of an attraction that we find only in Marianne from Delacroix’s “Liberty Leading the People”.

The subtlety, complexity and thematic range of the novel are extensive. Olivier’s observations of American democracy, though biased at times, are disarmingly witty. However, Parrot is Carey’s greatest invention in the novel. Carey’s purpose is not historical analysis or a distillation of the essence of present from the grove of the past. He addresses the one great issue: human relations and survival. Prism-like, the novel generates an entire spectrum of hues we find in human relationships from the permutations of class, psychology and politics to the intricate feelings of love and sexuality. Masterful, entertaining and splendidly shrewd, Parrot and Olivier in America is Peter Carey at his best.

Published in The Express Tribune, September 19th, 2010.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ