CHAGMALAI:

In a Pakistan army base high in the mountains on the Afghan frontier, a general explains a strategy for fighting the Taliban he calls simply “WHAM”.

The name has a distinctly bellicose ring. But the soldiers are learning to fight a new kind of war in this region.

“WHAM - winning hearts and minds,” explains the straight-talking General Nazir Butt, in charge of converting the army’s gains on the battlefield into durable security. “The plan is to turn militant sanctuaries into safe havens for the people.”

The term WHAM has been used before, but the focus this time is South Waziristan, an enclave on the Afghan border once the epicentre of a spreading Pakistan Taliban insurgency.

According to the army narrative, the campaign includes winning over the region’s Pashtun tribes through dialogue, creating commercial opportunities and providing education in new schools and colleges.

However well-meaning the new approach, there are problems that won’t go away - threats of retaliation by al Qaeda-linked militants, a lack of effective civilian administration and endemic corruption.

Road to development?

In 2009, Pakistan’s army chief ordered the biggest offensive yet, pouring 40,000 troops into South Waziristan in a bid to tip the balance.

The offensive displaced almost half a million people as homes, schools and hospitals were turned into hideouts by militants and meagre civic amenities were destroyed.

“The people can only feel fully secure if there is social and economic uplift,” said a brigadier who commands a cliff-side compound near Wana. “It took some time but we know now that 1,000 bullets can’t do the work of one school.”

Many of the refugees have resettled in Chagmalai, a village close to Jandola, where the army is headquartered in a fort built by the British in the nineteenth century.

A small, colourful marketplace was inaugurated last year and the green-and-white Pakistani flag was painted on the shutters of shops given to traders for a nominal fee. In a courtyard next door, army officers and government officials teach people how to raise poultry and set up bee farms.

But despite the development, Chagmalai still resembles a ghost town, a collection of ruined houses and abandoned clinics and schools with falling plaster and bullet-pocked walls.

A few kilometres away, construction workers and army engineers have dug through rugged terrain to build a road, which will connect the isolated region with Peshawar. The US government has contributed $170 million for the 287km road.

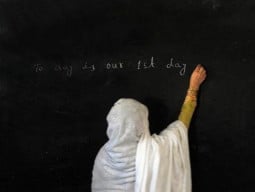

Imparting education

The army believes it can create goodwill by encouraging commerce and, more importantly, education. Officers say 33 schools have been restored and 4,000 students enrolled, 200 of them girls, but verifying such data is difficult.

Having previously served in the disputed border region between Pakistan and India, Colonel Asim Iqbal now shows off a flagship technical institute and cadet college built as part of the WHAM initiative.

Seventy-five students graduated from the 11-million-rupee Waziristan Institute of Technical Education in December with diplomas in auto-mechanics, carpentry and IT. Nearby, a cadet college has been built at a cost of 500 million rupees.

But for all the high hopes, there is little sign of a credible civilian administration taking root.

The highest political officer in the area, the political agent, does not even live in South Waziristan out of fear of being killed by the Taliban, who have murdered hundreds of leaders in the tribal belt in recent years.

Pashtun elders said official records showed that school teachers absent for months were still drawing salaries while the administration took no action.

But political agent Shahidullah Khan said he was doing the best he could. “There is only so much I can do when I can’t even travel outside the army camp,” he said by phone from Tank.

A tribal elder whose family has moved away and is too afraid to return, asked: “If the Taliban are really gone for good, why doesn’t the army also leave?”

Published in The Express Tribune, February 4th, 2013.

COMMENTS (5)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ

Kudos to army.

@Arjun: Dude, that was just lame.

WHAM doesn't seem to be working against the taliban's BAM...

Perhaps the next step is thank you ma'am?

WHAT!!!. Army took advice of "Taliban Khan" and started doing what he has been asking for years.

Kudos to Pakistan Army for its 'WHAM' initiative. Army should be appreciated for making efforts in high-danger area. However it would have been better if the army would have had received political support for this cause. Hope Our army really wins the hearts and minds of the local population.