Topi drama: The hat matters as much as the head

Thinking about starting a revolution? Well, don’t forget that all-important accessory: the hat!

Thinking about starting a revolution? Well, don’t forget that all-important accessory: the hat!

But that did lead us to wonder where exactly Qadri got his awesome headgear from and exactly what it symbolizes? Around the same time, there were also TV promos of televangelist Amir Liaquat sporting something very similar over his styled locks. So after exhaustive and painstaking googling research, it turns out that this is, in fact, a version of the Rumi topi of old, now wrapped in cloth. Also called the Tarboosh, or more commonly, the Fez, the Rumi topi really has nothing to do with Maulana Jalaluddin Rumi. Instead, it refers to Rum (Rome), which is what the medieval Muslim world called the Byzantine Empire. Oddly enough, it doesn’t actually come from Byzantium and instead originates (big surprise there) from the Moroccan town of Fes.

But the red Fez, as we know it, is most commonly associated with Turkey…so how did it get there?

Back in 1862, Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II had had enough of being pushed around by his elite military force of Janissaries and decided to put them in their place. No longer could his rebellious soldiers wear the flowing robes and turbans of old, but instead had to sport European style clothes and ditch their turbans. The modernizing Sultan decreed that his military and bureaucracy would now wear the Fez (along with the cloth wrapping) as a symbol of the ‘new and improved’ Ottoman empire.

This was easier said than done, as the Turks were very attached to their turbans. They didn’t just keep the sun off, but also symbolized status, wealth and rank. In effect, a big turban meant you were a big shot. In fact, just 400 years before this, Turkish envoys to the court of Vlad Dracul of Wallachia annoyed the vicious Vlad by refusing to take off their turbans as a show of respect. Dracul, who had a fondness for impaling people while he had lunch, then ordered his guards to nail the envoy’s turbans to their skulls ‘so that they never come off again.’ Talk about losing your head.

Anyway, Mahmud II’s orders took hold and soon the Fez was all the rage in the Ottoman Empire.

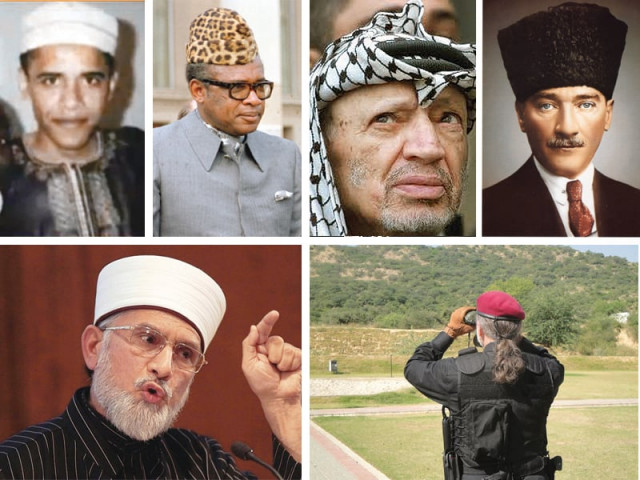

But eventually, matters came to a head once again when Kamal Ataturk took power following the Ottoman Empire’s disastrous defeats in World War One. Ironically, he saw the once-modern Fez as a symbol of Turkey’s decadence and decline and decided to chuck it out in 1925.

But the Turks loved their Fezes, so what was Ataturk to do? Travelling to the Turkish port of Inebolu, which had fought off Greek advances under his leadership, Ataturk wore ‘western’ clothes and a Panama hat, and declared: “The people of the Turkish republic, who claim to be civilized, must prove that they are civilized by the way they appear.” After explaining that they should now wear shoes, shirts, trousers and ties, he added, “and to complete these, a cover with a brim on our heads. I want to make this clear. This head covering is called a hat.”

For good measure, he also reviled the Fez as a “Greek headgear” to the highly nationalistic residents of Inebolu. A day later, he ordered all civil servants to ditch the Fez, and also imposed punishments of up to 15 years for ‘anti-hat propaganda’

Not all Turks were willing to doff their Fezes of course, and soon anti-hat riots erupted in several towns, and a healthy Fez-smuggling industry also sprang up. Over the next few years, dozens of people were executed and several hundred imprisoned for being too fond of their Fezes.

50 year old Islamic scholar Atif Hodja was one of the unlucky ones. On a cold winter night in December 1925, policemen arrested him from his house and kept him in custody for weeks without letting him meet his family. When he was finally put on trial, he found that his crime was penning a booklet titled The Brimmed Hat and the Imitation of Francs. In this, he argued that brimmed hats were a symbol of the West and that a Muslim, while wearing them, could not touch his forehead to the ground during prayers, thus effectively saying “I don’t bow down to God.”

The court acquitted him because the booklet had been printed before the Fez ban, but then a vengeful government put him before a Kangaroo court which sentenced him, and another cleric, to death. The message was clear: put on a hat or lose your head.

Had Ataturk not banned the Fez, the Jinnah cap may never have come into being. When the Quaid attended the Lucknow session in 1916, he sported a Fez and Saville Row suits. By the time 1937 rolled around, he had swapped the suit for a sherwani coat but, since the Fez was out of fashion, was at a loss as to what to wear on his head. According to Stanley Wolpert, author of Jinnah, “his eye was attracted to a black Persian lamb cap worn by the Nawaz Mohammad Ismail Khan, one of the greatest provincial League leaders. He asked his friend if he might try on the compact cap, which would soon be known throughout the world as a ‘Jinnah Cap.’ When he saw in a mirror how handsome it looked over the white of his sideburns, he knew it was just the headgear needed to give his Muslim costume its crowning touch.” Thus was born the Jinnah cap, known to the world at large as the Karakul (which means black fur in Turkish). While Jinnah may have popularised it, the Karakul has been worn by every Afghan king or president from Amanullah Khan to Karzai. Even Soviet leaders such as Brezhnev sported the Karakul, and in the ‘classless’USSR, it became something of a status symbol. Jackie Kennedy also wore one on a visit to Pakistan!

The Karakul also made its way to Africa, where an ‘Africanised’ version of it was worn by Congolese dictator Mobuto Sese Seko. This leopard-skin Karakul was so beloved by Mobuto that he actually made it illegal for anyone else to wear one! It’s probably safe to say that only the leopards missed him when he was gone.

Of course, none of this ‘banned and out of fashion’ business made any difference to Pakistan’s Nawabzada Nasrullah Khan, who continued to sport his trademark red Fez until his death in 2003.

While the Jinnah cap made its way to Africa, did you know the Gandhi/Nehru cap so beloved of Indian politicians (and Anna Hazare) actually came from Africa? When Gandhi was jailed in South Africa, he had to wear the uniform given to ‘negro’ prisoners, which included a very similar cap. When he returned to India, he brought it along with him. According to Gandhi’s close friend Henry Polak, this was the genesis of the Gandhi cap! Not all too surprising when you consider that the Indian subcontinent was once a part of the African landmass, way back in the day. Maybe this was Gandhi’s way of tipping his hat to the (original) homeland?

Of course, another African export recently made it to the top post in the US. Yes, I’m speaking of none other than Barack Obama. As the first black man in the White House, he sent the American right into a frenzy of scaremongering and conspiracy theorizing that would put most Pakistanis to shame. He’s a Muslim! He’s a socialist! He’s the Antichrist! And to justify at least one of these claims, they circulated a picture of Obama wearing a (shudder) African Kufi hat; proof positive for the Tea Partiers, if no one else.

If you think that was an overreaction, then brace yourself for the infamous Keffiyeh episode! This chequered headdress, traditionally worn by Arab farmers, became a symbol of Palestinian resistance when Yasir Arafat started sporting it. Today, a black and white Keffiyeh means support for Fatah while a white and red one means you’re a Hamas supporter. Now check this out: In 2008, Dunkin’ Donuts ran an ad campaign with their poster girl Rachel Ray wearing what looked like a Keffiyeh around her neck. The right-wing blogosphere went insane, accusing Dunkin Donuts of supporting ‘violent Jihadi terrorists’. The fact that it was in fact a paisley scarf and not a Keffiyeh was lost on the ranters, and Dunkin’ had to pull the ad. I think it’s safe to say that the nutjobs raving about this weren’t just sipping on cappuccinos.

Obama-haters, the Tea Party being chief among them, also have a certain fondness for haberdashery, only their choice of chapeaus harks back to the American Revolution with the distinctive Tricorne hat. You’ve seen this one on George Washington’s head and in just about every American-Revolution era movie from Last of the Mohicans to Mel Gibson’s Patriot. But Hollywood almost never gets it right and the most popular headgear during the American Revolution was in fact the Liberty Cap, known throughout history as the Phyrgian cap. This soft, red, conical cap (kind of like a ski cap) was originally worn by freed slaves during the Roman Empire and so became a symbol of liberty. Not only was it popular in the American Revolution, but also the French revolution, where it became a symbol of radical revolutionaries. With head-chopping becoming so popular and easy thanks to the guillotine, lots of ‘suspect’ French citizens started wearing the ‘bonnet rouge’ (red cap) on their heads just so that they could keep their heads on their shoulders!

Hats have always been important revolutionary symbols, and the same was seen during the Chinese revolution. All of a sudden, the nondescript cap worn by Mao-Tse-Tsung during the Long March (the real one, not the cheap Pakistani imitations) became a revolutionary symbol and a compulsory part of the uniforms of the revolutionary Red Guards, the terror of capitalist running-dogs and imperialist pigs everywhere.

But if the Mao cap was for the beloved sons (and daughters) of the revolution, those who fell afoul of the new order had caps of their own: Dunce caps! Enemies of the revolution like teachers, landlords and anyone with more than a basic education would have to wear tall caps with insulting messages like “I am a capitalist cow-demon,” while parading through towns and having little kids pelt them with rotten vegetables. The dunce cap may have fallen out of fashion since then, but the Mao cap, like the Lenin worker’s cap, was adopted by leaders across the world, including our very own Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

Of course, few pieces of revolutionary headgear are as widely known and popular as the Che Guevara beret. Although it dates back to the ancient Greeks and was re-introduced in modern times by the Basques of Spain, no one has done more to boost berets than Che himself. Not even if we count (the artist formerly known as) Prince singing “Raspberry beret.” The famous picture of Che taken by Alberto Korda (the one you see on T-shirts everywhere) elevated the humble beret to being the headgear of choice for wannabe guerillas and revolutionaries everywhere. Including, of course, Zaid Hamid.

So the next time you’re out there, shouting slogans and plotting the downfall of the oppressor of the day, don’t forget that what’s on your head matters as much as what’s in it.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, February 3rd, 2013.

Like Express Tribune Magazine on Facebook to stay informed and join the conversation.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ