268th Urs: Bhittai’s work should be translated for global recognition, say speakers

Writers, poets, intellectuals and historians come from India, America, Canada .

Almost all the writers, poets, intellectuals and historians, from India, America, Canada and Pakistan agreed on this fact at the nine-hour-long International Adabi Conference at Bhitshah held for the saint’s 268th urs.

Vimmi Sadarangani from Gujrat in India said that Bhittai was not given his due place in the world because his work wasn’t translated in major languages. According to her, Rabindra Nath Tagore won the Nobel Prize for his book, “Gitanjali” because it was translated from Bengali.

Sadarangani read her paper on, “Translations in Indian languages of Latif’s poetry.” She said that although Bhittai’s work was available in many languages in India, it did not hold together since the meanings of the words were changed because of the differences in vernacular and diction.

She gave an example: “Word Pireenh (beloved) was translated to Merey Piriya Bhagwan (my beloved god).”

Sadarangani said that a translation which maintains the sanctity of the original work can only be written by a Sindhi or someone who was intimately familiar with the place, its history and culture. While talking to The Express Tribune she shared that both her parents were from Sindh – her mother was from Hyderabad while her father was from Khairpur. Together her parents had written 11 books. The audience was deeply moved when she read her work on how the Sindhi Hindus in India pine for their motherland.

Indira Shabnam Poonawala emphasised how feminist Bhittai’s poetry was. The characters in his work, Marvi, Noori, Leela, Madhuri and Moomal were the epitome of a women’s love, courage, integrity and commitment. “They were women of exceptional valour who were loyal and brave,” said Poonawala. “They passed through mountains, rivers and deserts for their love. His poetry proved the stereotypical frail woman wrong.”

Another Indian writer, Hero Thakur, recalled the difficulties of migration in 1947. He said that it was his first visit to Pakistan after he migrated to India with his family in 1947, when he was only seven years old.

However, Thakur said, despite such epoch-making junctures in the history of Sindh, Sindhi Hindus who migrated to India and Sindhi Muslims who remained in Pakistan still remained close.

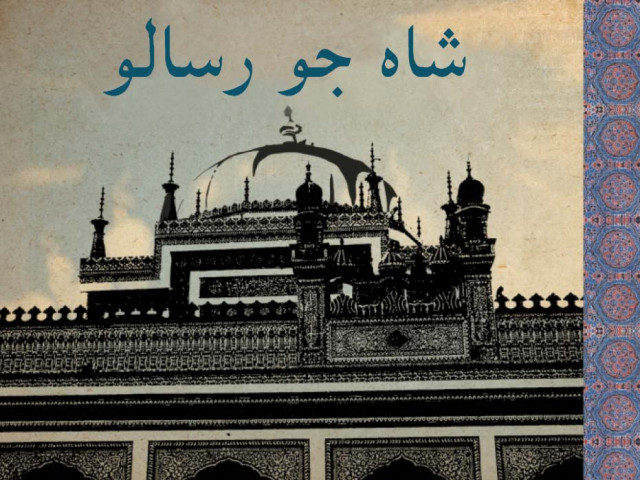

He attributed this intimacy among the people of the land to a history of co-existence and the influence the Sufi poets in old societies. Thakur reminded the audience about the efforts of Dr Hotchand Gur Bakshani for trying to get Shah jo Risalo recognised internationally. Bakhshani stirred up a debate in an Indian magazine in 1923 by drawing a comparison between Shah Jo Risalo and similar works produced in the West to show how Bhittai’s work lagged behind in recognition despite being a masterpiece.

Manzoor Aijaz, a Punjabi writer from America, discussed the concept of tasawaf (meditation).

He categorised sufis into those who followed religious and political authority and those who accepted it. “A saint is someone whose poetry contains the philosophy of life,” he said. “All those who have shrines and followers are not saints.” He pointed out that Bhittai’s poetry was not translated in Punjabi and requested that the culture department of Sindh do it soon.

Ghulam Nabi Sami, a writer from Jacobabad, said that Bhittai brought about a revival of Sindhi language which was overshadowed by Persian being the official language in the reign of Kalhora dynasty. He found elements of Karl Marx’s socialism and also of the romanticism of William Black, John Keats and William Wordsworth in Bhittai’s poetry.

A poet from Bhawalpur, Shazia Babur, said, “The Sufi poets kept the Sindhi language and culture, which was being ruled over by foreign dynasties, alive.”

“No other poet can wrap up every bit of culture, language, society, governance and religion within the geographical limits of Sindh the way Latif did,” said Prof. Javed Chandio, from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. “Instead of asking God for justice, Latif’s yearning was only His blessings.”

Amar Jalil, however, differed from the other speakers. He said that Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai only dared to speak between the lines when he challenged authority. “He was different from Sachal Sarmast and Mansoor Hallaj who were candid in their criticism and paid for it too,” he said. Both the poets he mentioned were killed.

Other speakers included Prof. Jameel Ahmed Paal from Punjab, Shumaila Hemani from Canada, Shah Muhammad Mari, an author from Balochistan, Saadullah Jan Barq from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Muhammad Hassan Hasrat from Gilgit Baltistan and Fehmida Riaz.

The conference was organised by the culture department of Sindh for the poet’s 268th Urs celebrations on Tuesday. However it was the last event of the year because the celebrations were cancelled after the death of Pir Pagaro on Tuesday night.

Published in The Express Tribune, January 12th, 2012.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ