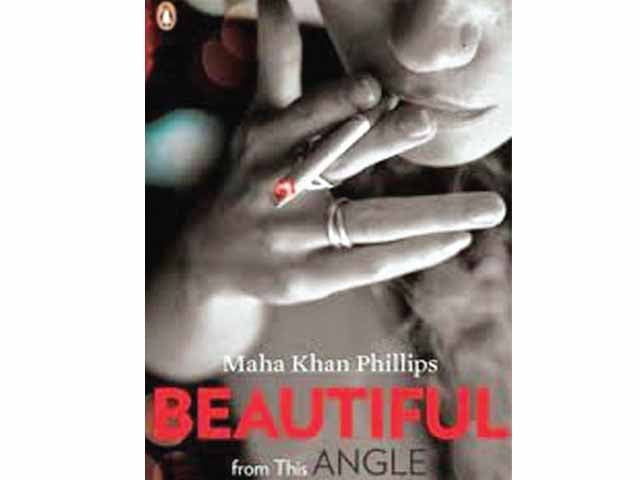

Beautiful from this Angle: Not just ‘chick-lit’

The Karachi party scene is not a world we are used to seeing in literature - sex, drugs, media wannabes et al.

Beautiful from this Angle: Not just ‘chick-lit’

The Karachi party scene is not a world we are used to coming across in literature and in Beautiful from this Angle Maha Khan takes a satirical look at a self-absorbed elite made up of socialites, media wannabees, drug barons and feudal landlord-politicians.

The idea is not unfamiliar. The pampered upper class comes face to face with the reality of the common (wo)man, attempts to ‘do good’ (with a big dash of self interest) with unforeseen and disastrous consequences. But Maha Khan makes it work. Mixing humour with a fast paced, no-frills style, she has the reader turning the pages until the story’s tragic end.

The novel’s protagonist is Amynah Farooqui who writes a weekly column in a newspaper (“Party Queen at the Scene”) and whose life of drugs, alcohol and casual sex is frowned upon by her best friends Henna and Mumtaz.

Henna is the daughter of a feudal landlord-politician and wants to help her childhood village friend, Nilofer, who she discovers is being brutally abused by her husband. Meanwhile, Mumtaz, a drug baron’s daughter, wants to advance her media career by making a documentary pandering to the west’s stereotype of Muslim women being oppressed ‘by Islam’.

The friends arrange for Nilofer to disappear and use her story as the basis for the documentary, A Matter of Honour. The documentary achieves unexpected success leaving Nilofer house-bound and her husband facing the gallows for her ‘murder’.

As the friends grapple with this situation, they are also going through upheavals in their personal lives. Amynah falls in love, Mumtaz transforms into a ‘women’s rights activist’ and Henna tries to come to terms with a marriage she is unhappy with. The events strain their friendship and draw them apart. There is tragedy at the end which jolts Amynah out of her drug-induced stupor and into a more meaningful life.

Throughout the novel the author parodies the media and its perception of Pakistan as being either about terrorists or downtrodden women and the way it suits the elite to perpetuate this myth. In the documentary the friends use make up to ‘create’ fresh bruises on Nilofer’s face and suggest that she has not ‘disappeared’ but has been murdered by her husband. Monty Mohsin, another regular on the party scene, is making millions through his Channel 4 reality show “Who wants to be a terrorist?”. And Amynah makes a half-hearted attempt to write the stereotypical ‘oppressed woman novel’ to try and catch a lucrative ride on that particular bandwagon.

The only character (other than Nilofer) who escapes the writer’s irony is Henna. As the dutiful only child of a feudal politician trying to make up for not being a son, her attempts to ‘do her duty’ are shown as genuine and her character, though not without faults, is not caricaturised. In fact the mocking tone is mostly absent in relation to the village scenes which are lovingly described, and only crops up in relation to the city folks’ interaction with the village. The author’s romance with Rahim Yar Khan where she spends her winters on her family’s farm may provide a clue as to why.

Beautiful from this Angle is available in Pakistan at most leading bookstores. It has been published in France and by Penguin India but has not found a publisher in England. UK publishers apparently thought it was ‘chick-lit’ and did not have a market. Much of the novel’s humour is aimed at western perceptions and perhaps they failed to get its point. As for us, not only will we get it, but if we’re honest we may just recognise something of ourselves in the novel’s absurd and selfish characters.

Crazy beautiful

Q: You mentioned that publishers in the UK viewed your book as ‘chick-lit’. How would you categorise your work?

A: I see the book as dark comedy or satire. It’s funny and light hearted but maybe has a point too. Sometimes I think humour is a really good way of talking about serious issues. That’s what I wanted to achieve.

Q: Do you see the book as having a ‘message’?

A: It’s incredibly frustrating to be a Muslim in this country and get barraged by comments about how Islam is such a terrible thing for one reason or another. I keep getting questioned about what happens to women in Pakistan. People also ask me how I can take Rehan (my son) back to Pakistan — people wonder whether I worry for his life or not. While elements of what the west perceives us to be are true, other elements are just fabrications. What the media tells you is not what you and I sitting at home in Karachi, or wherever, experience on a day to day basis.

Q: You satirise the media’s obsession with ‘the oppressed Muslim woman’ but don’t you think you end up saying that this is in fact the reality for most women?

A: I don’t think you can say that women don’t experience difficulties in Pakistan. I think a lot of tragedies take place, we all know about them. I didn’t want to belittle that by writing a book without anything happening to anybody. At the same time you can’t just blame religion for what’s happening. Our structures allow institutional violence. We should reform the police, reform the judiciary, why is it just Islam that is to blame? I accept that you can’t ignore the part that extremism or a misguided notion of Islam plays but you can’t ignore the part that a lack of education plays either.

Q: The book begins with an angry letter from a man in Texas which says it is the media’s responsibility to give a voice to ‘the real Pakistan’. Do you think he’s right?

A: What I had in mind when writing the letter was how Pakistanis living abroad think that Pakistan should be a certain way. There is a lot of extremism in Pakistan (continued on page 26) but there is also a lot of misguided extremism outside the country, where people have an idealised notion of Pakistan. The problem is that there are too many realities in Pakistan, it is full of contradictions. We’re all part of the problem. We can be part of the solution but we’re very much part of the problem.

Q: The book gets more and more serious as we go along. Do you see it as Amynah’s journey to a kind of awakening?

A: In the first ending I wrote she doesn’t reform at all and there was no ‘salvation’ so to speak, or not even the hint of salvation that the ending now has. It may have been more realistic but I found it too depressing and it just did not work.

It is a satire so I’m not suggesting that everybody I know in Pakistan is that clueless but I do think that we could just do with a reality check. As I said we are part of the problem.

Q: You avoided writing extensively about the characters in this book that belonged to a lower income group — we only saw them through Amynah’s eyes, as irritants. Do you think you would be comfortable writing about such people?

A: I wish I was. That was definitely something I struggled through with the book. But I’m an American School brat, I grew up in Defence, I went to a lot of parties. By the same token I did spend a lot of time in Rahim Yar Khan where my family has a farm. But it’s hard to get in the head of people unless you’ve experienced their lives in some way that is other than superficial.

I had an uncle, Khalid Akhtar, who was an Urdu satirist and he left his home for months at a time and immersed himself in these worlds and as a result became a brilliant writer. I’m afraid I haven’t done that and I wasn’t setting out to do it.

Q: How do you think people in Pakistan will respond to the sex and drugs in this novel?

A: I wasn’t trying to say that every young person in Pakistan is an alcoholic or drug dealer. My point was that there is this other extreme and it’s not right either. Personally I have been exposed to that world but of course I’ve exaggerated it, that is the purpose of the satire. I have friends who are or have been part of that scene. While there was no attempt to represent anyone, all those stories are based on some truth.

I haven’t had any negative feedback yet and I can’t see anyone being bothered. On the other hand after a review on BBC Urdu’s website I got a lot of weird Facebook friend requests from people who assume that I am like my character!

Q: So you think your book will only be read by people who belong to your world?

A: I think so.

Published in The Express Tribune Sunday Magazine, January 9th, 2011.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ