Education in Gilgit-Baltistan: In Diamer, only four girls go to middle school

Some districts in the region have the worst gender imbalance in education in the entire country

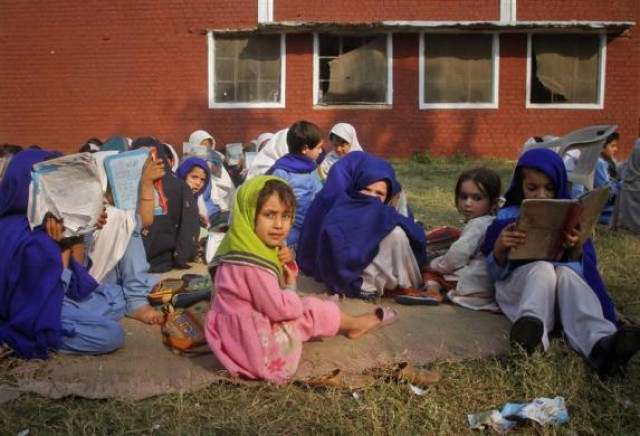

Some districts in the region have the worst gender imbalance in education in the entire country. PHOTO: REUTERS

If you are a girl in Diamer, Gilgit-Baltistan, who enjoys going to school, you are out of luck. In a district with an estimated population of 200,000-plus, only four girls attend middle school, a dismal situation that is the product of a confluence of adverse factors, including a difficult geography, insufficient government resources and cultural biases against women’s education.

This startling statistic was revealed in a report titled ‘State of Children in Pakistan’ released by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The report indicated that education in G-B in particular is in drastic need of attention from the regional government, which currently has not yet formulated a policy on education or children’s rights.

According to the report, a total of 221,998 students are enrolled in all public schools across the region, of which 127,129 are boys and 94,869 are girls. A slightly smaller number attend private schools in the region, many of which are operated by the Aga Khan Development Network.

Of the total number of students in public schools, nearly half – 97,213 to be precise – attend primary school. Given the region’s estimated population of 1.3 million, and including the number of children who attend private schools, the gross enrollment ratio (GER) for primary education in G-B is close to 100%. However, that number hides some disparities, specifically with respect to girls’ education.

While the gender ratio is roughly equal between men and women, the number of boys attending primary school is higher by over 8,000 compared to the number of girls. Specifically, there are 52,699 boys in public primary schools but only 44,514 girls. As bad as the situation is at the primary level, however, it gets worse at higher levels.

By middle school, nearly half of all students drop out of the education system: there are 55,651 students at public middle schools in the region, of which 32,332 are boys and 23,319 are girls. The overall numbers hide a wide variation in the region’s districts.

In Ghizar, girls’ enrollment is the same as boys and, in Gilgit and Hunza-Nagar, there are more girls than boys. On the other hand, in Diamer, while boys are sent to school in respectable numbers, girls are not. There are only four girls in middle schools in Diamer. In Astore, boys’ enrollment levels are also low.

In Baltistan, there is little difference in the enrollment of girls and boys in both Skardu and Ghanche districts. Here, too, a massive wave of dropouts occurs during the transition from primary to middle school. In Ghanche, there are more girls enrolled in primary school than boys, but there is drastic drop of almost half of both boys and girls in middle school.

The situation improves somewhat by high school, when enrollment goes back up to 69,134, of which 42,098 are boys and 27,036 are girls. The numbers are helped in part by students who previously attended private schools.

Distance, culture, and bias against girls’ education have had a serious impact on the participation of girls in education, especially at the middle school level and above. The issue is particularly acute in Diamer and, to some extent, in pockets of Skardu, both of which perform poorly on girl’s education due to a more pronounced gender bias.

While the government has historically not invested in education in G-B, the problem is exacerbated by geography. Population density is low as people live in tiny villages amidst the highest mountain range in the world. To offset this problem, the government has opened small schools with a multi-grade system in isolated areas. As a consequence, there is a proliferation of schools, but many lack quality staff and the basic requirements of a school. G-B has the highest number of primary schools per capita in Pakistan, with the smallest number of teaching staff. There are a limited number of informal schools for dropouts or children who have never attended schools.

Prior to the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, education was funded by the federal government, and G-B did not even have a regional government. Now that the G-B government has been given autonomy, it needs to learn how to exercise it with respect to policy formulation and implementation.

Published in The Express Tribune, May 25th, 2015.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ