Mental health care: Mind matters

Why mental health care is still lagging behind in Pakistan and what can be done to improve the state of affairs

Mental illness has dramatically increased in Pakistan for a number of reasons. A lack of understanding often breeds distrust towards medical professionals, rendering it difficult to make an informed decision. Some are reluctant to take medicines over fear of dependency and therapeutic treatment is opted out of due to the costs involved. Another reason is limited awareness about how the brain functions and the chemicals that govern it. In South Asia, mental illness is often attributed to black magic or possession by demons when, in reality, it is mostly caused by an imbalance of chemicals in the brain.

A lack of consensus among professionals regarding the provision of mental health care is also to blame. A few mental health professionals argue that in some exceptional cases, patients need a spiritual cure along with medical treatment. They believe that an integrated holistic approach, encompassing the mind, body and spirit, are the key to unlocking the mind. Therefore, to allow patients to make an informed decision, we take a look at the various facilities and treatment options available in the country.

In private care

For a population of 180 million, there are only five psychiatric hospitals in the country. However, several big private hospitals, including Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH), have a psychiatric ward for mental health patients. The AKUH in Karachi has a psychiatry department which includes six full-time psychiatrists and two full-time psychologists, in addition to two part-time psychiatrists and one part-time psychologist.

People tie pieces of cloth at the shrine of Pir Mangho for quick recovery of their loved ones. PHOTO CREDIT: AYESHA MIR

The hospital also has a short-term adult psychiatric unit which includes 18 beds. Patients can be admitted either from the emergency ward or upon referral from a psychiatrist.

Research has proven that the earlier a patient seeks treatment, the better the recovery chances are for him/her, says Dr Mukesh Bhimani, a psychiatry specialist at King Saud University who has three-and-a-half years of experience as a consultant psychiatrist and has previously worked at AKUH. For instance, if untreated for a long time, schizophrenia can cause permanent disability. “Like any other physical illness such as diabetes, psychiatric illness also has underlying biochemical pathology. Hence, it is necessary that patients seek professional medical help upon the onset of symptoms,” adds Bhimani.

But help at private hospitals does not come cheap. “Many people can’t afford to see a psychiatrist. Once I met a woman from a remote area of Sindh who took a loan from her neighbours in order to pay for treatment in Karachi,” recalls Dr Shahin Haye Hussain, consultant psychiatrist, professor and clinical director of Markaz-e-Nafsiyat (Institute of Psychiatry and Hypnotherapy) who has also written a novel on bipolar disorder titled Badaltay Mausam. The standard fee charged by a psychiatrist at AKUH for the first visit is Rs2,940 while Rs2,000 is charged for every subsequent visit. Moreover, for a private ward patients must pay Rs14,500 and Rs5,930 for a semi-private ward.

To provide patients with a low-cost alternative, in 2003 Markaz-e-Nafsiyat, a private trust that is funded by zakat and income received from private patients, started providing free consultation and medication to deserving patients. Patients from a number of places in Balochistan, in addition to Sukkur, Mirpur and Larkana flock to the facility for treatment. In order to spread awareness, Dr Haye even set up a number of camps in Sukkur, Hyderabad and Karachi. However, over the past four years, she has suffered a number of setbacks due to security.

A devotee of Pir Mangho pays a visit to the shrine in Manghopir, Karachi during the annual spiritual festival called Sheedi Mela. PHOTO CREDIT: ARIF SOOMRO

From its inception until 2010, at least 60% of patients suffering from psychotic disorders were able to resume work after receiving treatment at Markaz-e-Nafsiyat. Patients suffering from other disorders, including depression and anxiety, showed 90% recovery.

Affordable but limited capacity

Several non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have been actively providing care to mentally ill patients at subsidised rates or no cost at all. Pakistan Association for Mental Health (PAMH), established in 1966, set up a free depot line clinic in 2002 in Karachi, offering free of cost outpatient services, such as psychiatric consultation, psychotherapy and psychological assessment. Deserving patients are also given free psychiatric medicines. But limited resources in terms of the number of psychiatrists, psychotherapists and counsellors means only a limited number of patients are offered services at the facility.

On the other hand, Karwan-e-Hayat has the capacity to accept more patients. They have a 100-bed inpatient hospital in Keamari, Karachi, which also has an outpatient department (OPD), pharmacy, rehabilitation services department and a separate ward for male and female patients, and a community psychiatry centre in Korangi, Karachi, which has an OPD, pharmacy and rehabilitation centre. They also run the Jami Clinic in Punjab Colony, Karachi, which includes an OPD and pharmacy. The NGO has been providing consultation, medicines, meals and rehabilitation services free of cost or at subsidised rates to more than 350,000 under-privileged mentally ill patients since 1983.

A male psychiatric patients’ ward at Karwan-e-Hayat in Keamari, Karachi. PHOTO COURTESY: KARWAN-E-HAYAT

Based on the number of facilities, Karwan-e-Hayat has a staff of 140 people, including five senior consultant psychiatrists, three voluntary psychiatrists and a number of clinical psychologists, rehabilitation practitioners, social workers, resident medical officers and psychiatric nurses. They also receive regular training to maintain healthcare standards. Recently, an illness management recovery programme was introduced along with a community psychiatry programme for unprivileged patients. The programme sets goals for patients to accomplish tasks, salvaging the skills they may have lost during their illness. Gradually, patients resume everyday chores and rejuvenate their estranged familial relationships. Many go back to work or continue their studies.

Of the 45,000 patients who received treatment in 2014, 80% were treated free of cost. Financial assessment is done by a monitoring and evaluation department at Karwan-e-Hayat where family members or guardians of the patient are asked a number of questions to evaluate the family’s financial status. The patients who get selected are provided with the utmost care. Sumera Naqvi, manager of corporate communications and resource mobilisation at Karwan-e-Hayat, says a 21-year old girl was brought to Karwan-e-Hayat by her family members who could not make sense of their daughter’s extreme mood swings. She was consequently diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder and prescribed medicines and therapy for a year. Today, she is married and has a baby boy.

Divine healing

Not all patients opt for medical treatment. Due to limited financial resources and awareness, fewer facilities and a firm belief in spiritual care, many approach mandirs and shrines for relief. For instance, many devotees of Hazrat Syed Pir Haji Ghayeb Shah Bukhari (RA), whose shrine is located at Kaemari, in Karachi, visit the place in hopes of getting their loved ones cured. One of them, Sarifan Bibi, mother of 20-year-old Sakina, says, “This is my second visit here. I believe Ghaib Baba will cure my daughter.” She brought her daughter to the shrine after doctors failed to diagnose her illness and cure her. Nasreen and Saira also brought their brother to the shrine after they thought he had become a victim to black magic.

Located on a hilltop overlooking Clifton Beach, the tomb of Abdullah Shah Ghazi is the most visited shrine in the port city. Khan Muhammad and his 12-year-old son Ali Asghar regularly visit the shrine after Asghar sustained a head injury in an accident. A few years after the accident, he started behaving oddly and talking to himself. A doctor ascertained a chemical imbalance in his brain but due to little faith in conventional treatment, Khan preferred to take his son to the shrine. “We stay here for a few hours and I take holy water from the shrine to sprinkle on Asghar whenever he cries,” says Muhammad.

As part of the treatment, patients attend a talk on mental well-being in a fitness room at Karwan-e-Hayat. PHOTO COURTESY: KARWAN-E-HAYAT

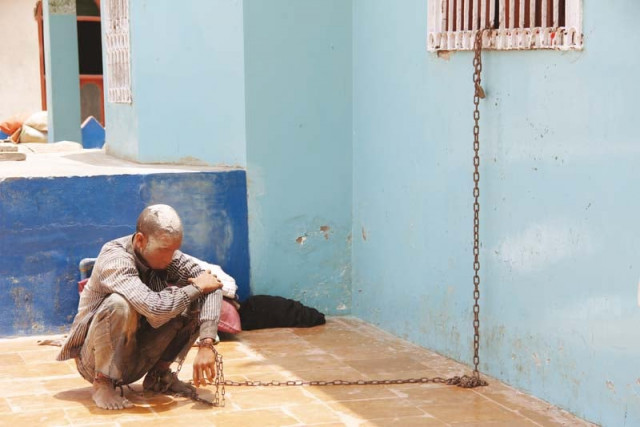

But spiritual healing does not always have all the answers. Many take advantage of dependency on religion to extract money from families and perform risky ‘exorcisms’. One Baba Ijaz Bengali was arrested by Garden police in Karachi for taking the life of Muhammad Ghani in an exorcism attempt. Ghani, 25, was brought in chains by his father and brother, but his condition deteriorated by afternoon from the constant inhaling of smoke that Bengali claimed was part of the treatment. After Ghani died, Bengali dismissed the death as “bad luck”, saying the former was possessed.

In another incident, a local cleric from Punjab, Maulvi Sarfaraz, was arrested by the police for burning the feet of an 11-year-old girl in an attempt to exorcise her demons after she exhibited signs of delirium, later discovered to be the result of typhoid.

The talking treatment

The recent divide between psychiatry and religion has made mental healthcare even more challenging. Most mental health professionals dismiss divine healing while patients show distrust of medical treatment as communicated through religious practitioners. To meet midway, psychotherapy or talk therapy is a way to treat people with a mental disorder by helping them understand their illness. It teaches people strategies and gives them tools to deal with stress and unhealthy thoughts and behaviour.

Sometimes, psychotherapy alone may be the best treatment for a person, depending on the illness and its severity. After assessment, however, if a psychotherapist feels the need for a patient to visit a psychologist or a psychiatrist, they refer them to one accordingly. “Whilst I work in tandem with psychiatrists for some of my clients, I personally feel it is better to see a counsellor or a psychotherapist first. I believe medicine should be the last resort,” says trainee humanistic integrative counsellor/therapist Samia Chundrigarh at the Centre of Personal and Professional Development (CPPD) counselling school in Karachi. According to Chundrigarh, the job of a counsellor/therapist is much less about diagnosing and more about facilitating the client to help them draw their own conclusions and either resolve or find coping mechanisms that match their individual needs. “It is only when people openly speak about their issues and experiences in counselling that the stigma will end,” she says.

The CPPD has been working with Alleviate Addiction & Suffering Trust for the last 12 years to improve the quality and standard of mental health practitioners in Pakistan. They run a counselling school, training students in the humanistic integrative approach. Humanistic Integrative Counselling recognises that there are significant connections between all approaches to counselling. It acknowledges that different clients have different needs and believes that no one single approach is sufficient. During the second stage of training, trainee counsellors are allowed to offer low-cost counselling services. Their fees range from anywhere between Rs10 to Rs500, depending on the financial status of the client.

Resolving the conundrum

As earlier perceived, prospects of mental health care in Pakistan are bleak, but even the available options can be availed by those who can afford it or access it. With time, even one-on-one counselling/therapy is getting expensive. To counter this and to make mental health care more accessible Chundrigarh plans is to establish a nationwide helpline manned by qualified and trainee counsellors who can provide assistance and information to people in times of stress and emergencies.

Additionally, Dr Bhimani urges launching awareness campaigns and educating the public through print, electronic and social media, along with organising seminars on mental health. Denial is one of the gravest hindrances in seeking help, he says. Most people will immediately seek medical attention in the case of a physical injury, but do not feel the same need when it comes to a mental disorder, he adds. This is often due to information asymmetry among patients and doctors. Patients need to be informed about the benefits of getting treatment and the final decision should then be left to them.

Roles of different medical professionals

Psychiatrists Unlike other mental health professionals, psychiatrists must be medically qualified doctors who have chosen to specialise in psychiatry. This means they can prescribe medication as well as recommend other forms of treatment.

Psychologists Their work involves dealing with the way the mind works and can specialise in various areas such as mental health and educational and occupational psychology. They are usually not medically qualified. Their work involves reducing psychological distress and enhancing and promoting psychological well-being.

Psychotherapists They are trained to listen to a person’s problems to try to find out what’s causing them and help them find a solution. As well as listening and discussing important issues with a person, a psychotherapist can suggest strategies for resolving problems and, if necessary, help you change your attitude and behaviour. Some therapists teach specific skills to help one tolerate painful emotions, manage relationships more effectively, or improve behaviour.

Counsellors Counselling is a type of talking therapy that allows a person to talk about their problems and feelings in a confidential and dependable environment. A counsellor is trained to listen with empathy (by putting themselves in others’ shoes). They can help one deal with any negative thoughts and feelings one has. Sometimes the term ‘counselling’ is used to refer to talking therapies in general, but counselling is also a type of therapy in its own right. The counsellor is there to support and respect one’s views. They won’t usually give advice, but will help one find his/her own insights into and understanding of one’s problems.

Source: National Health Service UK website

Komal Anwar is a subeditor on The Express Tribune magazine desk. She tweets @Komal1201

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, May 24th, 2015.

COMMENTS (1)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ