Divine secrets of the sufi brotherhood

Carl Ernst, a scholar of Islamic studies with a particular awareness of and empathy for Pakistani culture, follows Asani’s contribution with his remarks. Ernst’s essay addresses a series of interesting binaries in both an obvious and nuanced way, discussing the ‘breathless journalistic’ focus on the Taliban and Sufism, religion and Sufism, Salafism and, you guessed it, Sufism.

He also presents more interesting contradictions such as the erudition of religious scholars versus the popular culture celebrated by Sufis, the struggle past materialism towards the divine, as well as a one-lined critique of the Euro-American feminist tendency to view their own trajectory as the only possible model for Muslim women. The text is accessible and probably beneficial for western readers wishing to confound those convenient binaries, as well as South Asians indignant at the hijacking of Islam.

A highlight amidst the generality is the insertion of Ibn Battuta’s 14th century report about reaching the point in modern day Sri Lanka where Adam’s footprint from his earthbound descent is allegedly imprinted. This is used to introduce scholar Azad Bilgrami’s contention that India was where Adam descended then left to search for Eve, and tha, since we are all children of Adam, we are all in fact Indians. This almost jingoistic contention becomes perplexing when, a few lines later, Ernst discusses the problems of nationalism conferred upon religious leanings. By her own admission, Quraeshi’s book is an act of resistance against the interpretation of Islam as monolithic. How she attempts to go about it is through personal memory, storytelling and image making.

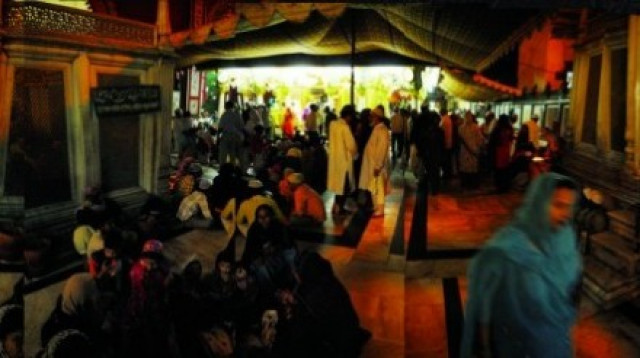

She relates her personal story of visiting a shrine, where she confessed, then prayed for, her most secret wish: to study in America. The bulk of Quraeshi’s contribution reads like a personal travel narrative, peppered with explanations of Sufi practices or concepts. Her concepts are simply mentioned rather than developed, leaving the reader looking for more of a response to the poignant duals introduced in the lengthy prologues. The book also includes an interesting commentary on Islamic art, such as the architectural contemplation of integrating a square into a circle, by a transitional space.

These details become starting points for the reader’s own contemplations about transition and space, if he or she is so inclined. If not, the reader has Quraeshi’s anecdotes as accompaniment, even if their highly subjective nature falls short of its earnest mark.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ