By policing schools, Punjab parks budgets in the right spot

Law on free education till you are 16 years old increasing accountability

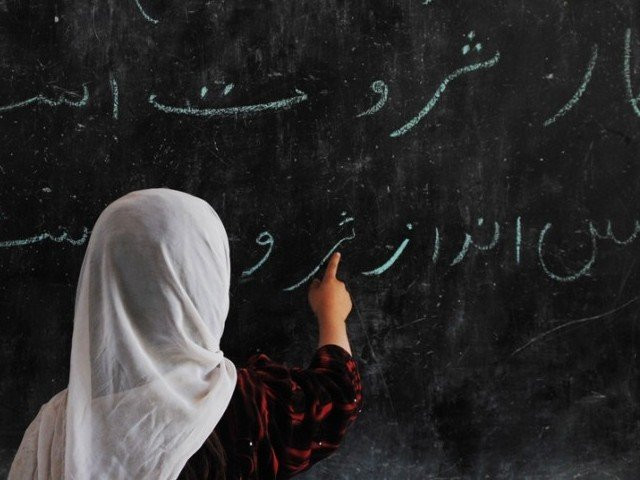

Law on free education till you are 16 years old increasing accountability. PHOTO: AFP

Schooling is a car. And in Punjab, the government wants to drive a Mercedes Benz.

It certainly seems to be on the way to getting one. For the last five years, it has poured impressive amounts of money into education. “We are on the right track,” remarks Qaiser Rashid, the School Education Department’s Deputy Budget Secretary.

This financial year, schools are getting Rs48 billion out of Punjab’s Rs1,349 billion budget, which is nearly Rs6.7 billion more than last year. Naturally, the department is excited. “You cannot progress at advanced educational levels unless you are determined to invest at the most basic level,” adds Rashid.

Indeed, it is to the most basic level that the money literally trickles down. The budget makers don’t dictate portions for primary, secondary or high schools. It is the districts, at the lowest tier, that make those decisions on their own. They are, of course, guided by overarching Punjab government policy. For example, if it says more kids need to be in school, the districts will spend on enrolment drives. Another policy is to close the gaps. So poverty indicators help tilt funding towards deprived districts, which are as many as 12 in southern Punjab.

The districts are empowered because a new bottom-up feedback mechanism will hopefully prevent corruption and peg funding to performance. Every month, the School Education Department sends teams to collect data on 14 indicators. They cover major spots from school environment to the quality of class tests. And just to be on the safe side, a third-party, Nielsen, vets the government’s data annually. This is a fairly new exercise, though. Independent analysts are waiting to assess long-term impact.

Because the districts manage their own accounts, the government data is opaque on how much in total goes to primary schools across the province. But the Institute of Social and Policy Sciences (I-SAPS) found in its own research that three years ago, Punjab started giving primary schools the most money from its education budget. This was, however, eclipsed by secondary education a year later. Either way, Punjab is giving these two tiers—and not colleges and universities—the lion’s share or 85% of the education budget. There is a clear reason for this.

Five years ago, with the 18th Amendment, Article 25-A was inserted in the Constitution, granting as a right free and compulsory education to all children from five to 16 years of age. And since education was a devolved subject, it was up to the provinces to implement the provisions within this law. So, Punjab made it mandatory to educate children up to the end of high school. It simply had to put in more money to achieve this.

The new law had a ripple effect. In addition to giving funding more muscle, it helped hold the system more accountable. “Now, statistics on drop-outs and out-of-school children are questioned,” says the department’s Rashid. “We see there is greater sensitisation and awareness in the Punjab.”

Just giving education a lot of money isn’t the end of the story, though. Taking a budget apart shows if it went to the right places. Consider the analogy of a car again.

The teacher is the driver. Get a qualified, well-paid driver and you will get a safe ride (salary component). But what about paying for daily petrol, oil changes, fixing a flat tire? That is the non-salary component, which in education’s case, is spent on things like administration, electricity bills and monitoring.

Traditionally, teacher salaries have taken up most of the budgets. And even though it is fashionable to bellyache that these numbers are too high, paying teachers well and on time is a winning formula. More students have stayed in school and enrolment rates have gone up. Small wonder then that I-SAPS found the government gave salaries 7% more in the 2013 budget.

Better still: the government allocated 20% more money for expenses other than paying salaries (non-salary component). This would go to, say, pay for monitoring teams or electricity bills. The only problem is that even though it set aside more money, it ended up actually spending 18% less of it. It is as if you were given 100 rupees but didn’t spend all of it.

This trend is worrying for Ahmed Ali, a research fellow at I-SAPS. “The non-salary component directly influences development and as such should be improved,” he suggests. “This is something we have been stressing for a long time.” But for whatever it is worth, the monitoring by the department’s own teams and Nielsen indicate that Punjab is putting some of its non-salary budget to good use. It seems to be headed in the right direction.

With writing by Hira Siddiqui in Karachi

Published in The Express Tribune, February 23rd, 2015.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ