Afghan presidency audit

A failure of mainstream but profoundly polarised politics in Afghanistan is unfortunately mirrored in Pakistan today

Afghan presidency audit

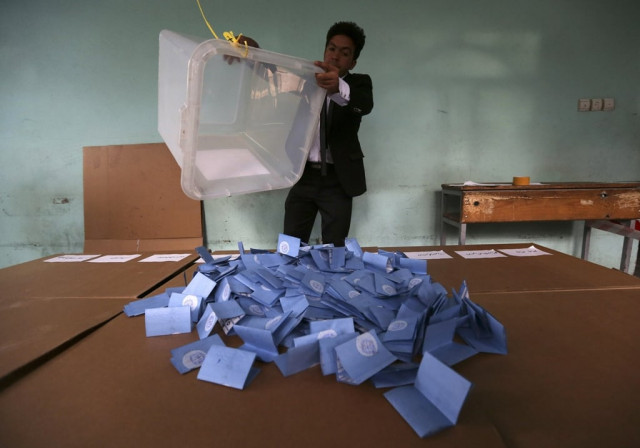

There are eight million ballot papers to be scrutinised. Each one has to be agreed or rejected by at least three people — representatives of the candidates and the UN scrutineer. With representatives withdrawn the audit continues, and is tentatively scheduled to be completed around September 10, but even if it is the likelihood of both candidates accepting the result is faint; and even fainter is the likelihood of the wider Afghan populace accepting whatever the audit decides is the final result. The UN continues to try to get both parties back to observing — and accepting — the audit and a UN representative has said on record that it is likely that Ashraf Ghani will be declared the winner on the basis of the audit thus far.

The future of Afghanistan is literally in the balance. A future that is closely linked to the stability and internal security of Pakistan. A failure to resolve the disputed election opens the possibility not only of a vacuum at the head of governance, but a return to the ethnic violence that preceded the rule of the Taliban. Ashraf Ghani is a member of Afghanistan’s largest ethnic group, the Pakhtun. Abdullah Abdullah is part Pakhtun and part ethnic Tajik. Geographically, Abdullah holds sway in the centre and north of the country, Ghani to the south and the east. The two groups have been at odds for centuries.

Even before the current dispute over the audit there were profound difficulties surrounding the creation of a government of national unity that was also a part of the Kerry brokerage. There are unconfirmed — but not denied — reports that some senior ministers are considering setting up an interim administration to take power when president Karzai finally vacates the presidential palace. Such a move would create yet another fault line in the much-fissured political landscape of the country, another supra-political bloc.

Afghanistan is not a country at peace with itself in any sense of the word. The war against the Taliban was not won by Nato and coalition forces, and they remain powerful in much of the south and east. In Kandahar and the surrounding areas they run a parallel administration. The Afghan National Army (ANA) may be no match for them in the event of protracted conflict, and find itself outgunned and outfought. The ANA will be losing the vital air-cover provided by the coalition forces, and loyalties within the ANA have proved negotiable to say the least. None of this bodes well for Pakistan. A failure of mainstream but profoundly polarised politics in Afghanistan is unfortunately mirrored in Pakistan today, and both countries have shaky democratic provenance. The army has come to the rescue of the politicians in Pakistan, but the ANA will not be doing the same for Afghanistan.

Published in The Express Tribune, September 8th, 2014.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ