The final destination: A trip to the realm of the dead

In a small cold storage room, lay around 50 unidentified, unclaimed bodies.

A terrible stench, of death and decay, greets you as you walk towards the cold storage room of the Edhi morgue. A few steps forward and a cold blast of air hits you in the face. Another few, past the plastic curtain, and you are surrounded by the dead.

The first room is filled with the bodies brought here for storage while arrangements for the last rites are made; 72 hours is the upper limit and a Rs1,000 charge for the service. The bodies here are covered entirely, save for a few. Faces of old men and women, peaceful and serene, peek through openings in the shrouds. The room makes one feel sombre but once you enter the second, slightly larger, room the ambience becomes altogether more haunting.

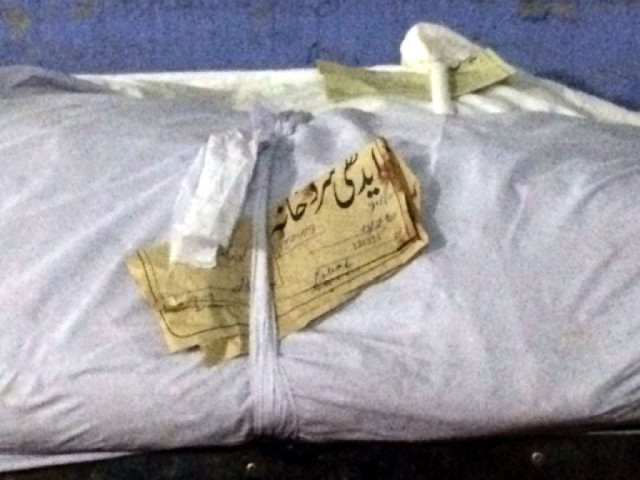

Here lie the unidentified ones, those killed in target killings, crossfire or traffic accidents, lives cut short horribly in one way or the other but no one to notice that they are gone. The bodies are worse off for wear and tear. They are wrapped with much less care, the knots on the ropes are hurriedly done and more faces poke through the cloth than in the last room; nameless faces, unknown and unidentified.

A few of the bodies have started to decompose, it is clear that they have been dead for more than the 72-hour limit. “Sometimes the body is discovered days, or even weeks, after the person has died and sometimes we have to keep the bodies here for an extended period of time on the request of the police if a case is ongoing,” explained Riyasat Ali Khan, the incharge of the morgue’s graveyard shift, who had a habit of scratching his unkempt beard when divulging the more gruesome details. “Sometimes, we even find bodies that have developed maggots in them so we have to wash them out really carefully before storing them since they represent a health hazard for us,” he said, scratching at his beard furiously.

The men who work here are not superstitious. They smile at being questioned about being afraid of the dead, but there is no twinkle in their eyes; witnessing so much death has made them cold.

The dead remain dead but the horrors that these workers have seen over the years have taken their toll. It is easy to see why; being surrounded by the dead left an entirely visceral fear that was hard to shake off. Here they lie, some decaying, some with a terrifying expression of fear permanently etched on their faces. Others had gone more peacefully and one fresh body even looked perfectly normal - of a man who could not have been more than 30 - save for a bullet-sized hole in his right temple, a recent victim of the city’s violent streak.

Placed on shelves, one on top of the other, they wait for someone to come and identify them. There are yellow tickets stuck crudely between the ropes; receipts of their deaths - where they were found, how and when they had died and nothing more than a number for recognition.

If no one comes to pick them up within three days, they are then buried in the nearby Edhi graveyard in Mawach Goth. On their tombstone there will be just a grave number to tally with that of the tickets - their pasts and their identities lost forever along with their names. They will have a funeral but they will not have an epitaph. They will have a grave but never will anyone visit it.

One final act still remains though before they are lowered into the grave; a picture is taken, just in case someone comes searching for them later on. With greasy fingers Khan sifts through the thick wad of photos; the last remaining remnants of the hundreds that have left us silently, almost unnoticed, over the years. Somewhere in this vast city, a mother waits anxiously for her son to return; lying here on the cold iron shelves, wrapped in a shroud and with a bullet firmly lodged in his temple, he never will.

Published in The Express Tribune, August 17th, 2014.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ