From Karachi to Gorakh: The simple villager who can humble the chief minister

Gorakh village residents say polio workers marked their houses but did not give polio drops.

Gorakh village residents

say polio workers marked their houses but did not give polio drops. DESIGN: MUNIRA ABBAS

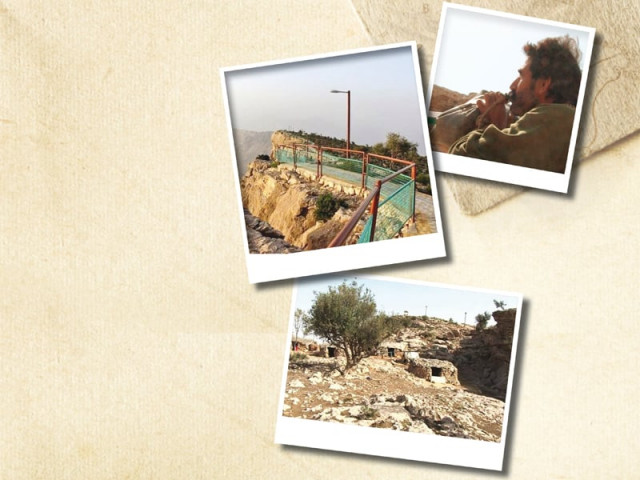

The chief minister visited the Gorakh Hills and handed over a cheque worth Rs300 to Nabi Bux, a resident of the area. “I thought I should give him Rs300 instead,” laughs Bux as he recalls the CM’s visit. The villagers living the lives of those from the Stone Ages love sharing the eccentricities of government officials.

“We are fond of the Pakistan Peoples Party because of Benazir Bhutto,” says Bux. In 2007, when Benazir Bhutto passed away, the villagers cried and mourned for the loss of their leader. But they are a practical bunch and they support whoever is in power. “We really don’t care about party politics,” he says.

“We own the Gorakh Hills but our claim is not even recognised by the government who uses our land as a tourist spot without giving us any incentives,” he complains.

According to Bux, were they to vacate the land today, it would no longer remain a part of Sindh. Bux estimates that the Gorakh Hill is almost “four inches” away from the territory of Khuzdar - district of Balochistan. On Benazir Viewpoint, the top of the hill that barricades the edge of the mountains, lies Balochistan.

Bux claims he has cousins across the border as his mother is a Balochi. At several times during his conversation, Bux asserted that he was a Balochi, not Sindhi. When asked if they frequently fought among each other at home, he replies: “Baloch hain, kaisey nahin jaghrengey?” [We are Balochis, how will we not fight?].

Sitting with the Bux family in the village, I wonder if the children are vaccinated against polio. “No, our children are not vaccinated,” he says as a matter of fact. “They [health workers] did come - not for the drops but to mark our houses with a number.” The villagers cannot possibly pay Rs4,000 to rent a four-wheeler and go down the hill to Dadu to get their children immunised.

“They are building lavish rest houses for themselves, what about our houses?” His uncle asks. Bux likes his mud-houses but he would like it if they could get better housing. “Hum yahan ke maalik hain or humey mulazim banaya hai,” [We are the owners here but we have been employed as workers], Bux adds.

“There was a time when we had to travel 12 kilometres barefoot to get a gallon of water,” he says. At least they get water supply now.

“My wife is ill but we cannot go to Dadu again and again, since the doctor has recommended constant medications for her,” he says, adding that lack of medical facilities has created many issues for them. They have, however, improvised conventional homemade remedies to cure their ailments. “We wrap goat skin around a snake bite,” he says, giving an example of such a treatment. “We are people of the mountains. We know how to survive.”

The villagers light a bonfire outside their houses to keep away monsters, such as wolves or dogs, at night. They keep the animal skin and let it dry under the sun for days, using it as a container for storing water. “The water stays icy cold throughout,” says Bux.

The village is not connected to the national grid but they have solar power generators on the rooftops of their houses. “Unparh hain magar na-ehal nahin” [We may be uneducated but we are not incompetent], he says.

The women in this village are respected. “I have seven children and a wife.” When asked if he will marry again, he replies: “A man only needs one woman.”

Published in The Express Tribune, April 26th, 2014.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ