Andaaz: Fine-dining your way through history

At a giddy three-floor rise, Lahore's Andaaz spells history, art and a passion for food.

Andaaz: Fine-dining your way through history

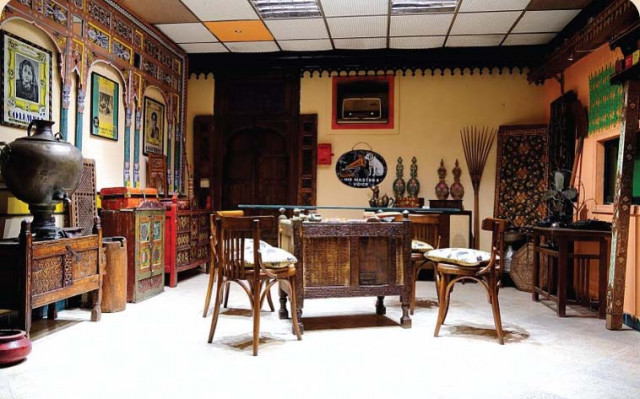

But, having inherited his mother’s passion for food as an art form, Ahmed nurtured his project with an aesthetic and historic edge — the result is Andaaz. At a giddy three-floor rise, Andaaz spells history, art and a passion for food. Silhouetted against the magnificent Badshahi Mosque, Ahmed says, “This had to be my first choice of location for the restaurant, given the menu. Food tastes best when complemented by the ambience.” The ambience is established as you scale the old world flight of stairs flanked with historical mementos and antiques; it is an artistic journey through time that prepares you for the culinary experience you’re about to have.

The class act of desi cuisine, which Cheema has laboriously salvaged from the currently rampant mixes in the market, needed a specific backdrop: royal and regal. Guests flocking for tandoor-grilled — not charcoal-burnt, mind you — delicacies cannot but imbibe the pervasive sense of history. Having made the choice between Mughlai dastarkhwan and solid furniture sittings, both settings under the open sky, they become part of the unfolding drama of time and taste. It’s not just the luminescent dome of Aurangzeb’s mighty mosque in the background that calls for a willing suspension of disbelief but the feel of a vibrant and alluring bazaar-culture that has not really changed with time.

Andaaz reflects Iqbal Hussain’s influence and Ahmed frankly admires the artist’s courage in breaking ground for a culinary venture in the heart of the old city. “I was like, ‘Oh wow,’ when I came to dine at Cuckoos as a student. Iqbal Sahib had changed the way people look at this area.”

The wow factor stayed put even as this restaurateur picked up technicalities at the Florida School of Culinary Arts. The excitement of that first exposure to the timeless ambience and rich culture of Lahore’s innards continued to marinade as Ahmed proceeded on a voyage of discovery: Calcutta, Goa, Peshawar, Sindh, Balochistan, Punjab, nothing was to be missed.

So, what makes Andaaz’s serving of bihari or malai or badami kebabs or Khyberi jhinga or mutton karahi or kajoo chicken not feel like having reinvented the wheel? “This is an effort to preserve the taste of desi food. I am not experimenting with recipes. I am using authentic recipes that have been eaten by people in these parts for ages. The battle is to keep the recipes unadulterated by modern day shortcuts. Changing the sequence of marinating or tampering with the order of adding the spices is a sure recipe for disaster. Sub-continental cuisine depends for its taste on basic spices but it’s the way you handle them that can bring out the subtlety of taste. Everybody uses cream and cheese in malai kebabs but take a detour by cutting on the marinade time and you end up losing the spirit of the meal.”

Thus guests driving down to Fort Road can be sure of the real thing; not the least being the tanginess of the tikkas or other grilled delicacies because Ahmed Cheema is a great disciple of the traditional tandoor. “Grill your meat over charcoal fires and out go the juices. The tandoor is the best oven ever invented,” says Ahmed, “Its shape ensures that you can get the high temperatures required for the perfect sajji. You see, in grilling you need to keep the juices inside the meat to prevent it from going dry.”

Cheema believes that serving food is also an art form seeped in history, which explains the demure damsels carrying hand-basinets and mini-hammams offering to help you wash your hands while you are rounding off your meal with paan masala picked off pewter platters. Having re-established the past, Cheema is however in no mood to put up his feet. Cheema next venture is going to be entirely, authentically present day.

Published in The Express Tribune, October 17th, 2010.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ