The problem is multifaceted. It is violent, creative, and it rages across the country. The methods vary, but also tie in together, like pieces of a puzzle. In a two-part series, The Express Tribune tries to unknot this problem: the dire straits of extortion.

In 2009, The Financial Times reported, “Taliban fighters have turned Nato’s huge logistics chain into a big source of funding by extorting money from hauliers and kidnapping their drivers for ransom,” it stated. “The militants’ ability to prey on the supply lines on both sides of the border shows how the Afghan conflict fuels a self-sustaining war economy in which the boundaries between insurgency, organised crime and banditry are blurred.”

These blurred lines hold true, especially for Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. Deteriorating law and order and the ubiquitous insurgency threat provide a fertile ground for extortion to burgeon.

Fringes of the border

In the key transit cities to Afghanistan, the opportunity for extortionists comes in the form of Nato supply trucks that drive through sparsely populated, sensitive zones.

In areas such as the Takhta Baig check post in Khyber Agency, and Chaman in Balochistan, truckers have complained that FBR-approved companies demand protection money from transporters carrying goods between check posts.

Ironically, although these private companies charge truckers for protection, they are unwilling to offer protection from kidnapping, killing and injuries.

Thus, what truckers call extortion is actually the ‘bonded carrier system’, which is essentially collateral truck drivers have to pay as security. While it is legal, truckers complain it serves no purpose and is an extra financial burden.

As a reaction, the Khyber Trailers Drivers and Workers Union suspended the Nato goods supply service in January this year and lashed out at the government for failing to ensure their safety. In response, a Nato/Isaf trucking company official told The Express Tribune, on the condition of anonymity, that truckers of the drivers’ union had protested pointlessly. “I think it is because they do not understand the bonded carrier system. In the two years that my company transferred Nato goods to Kabul, we never had complaints.”

The city life

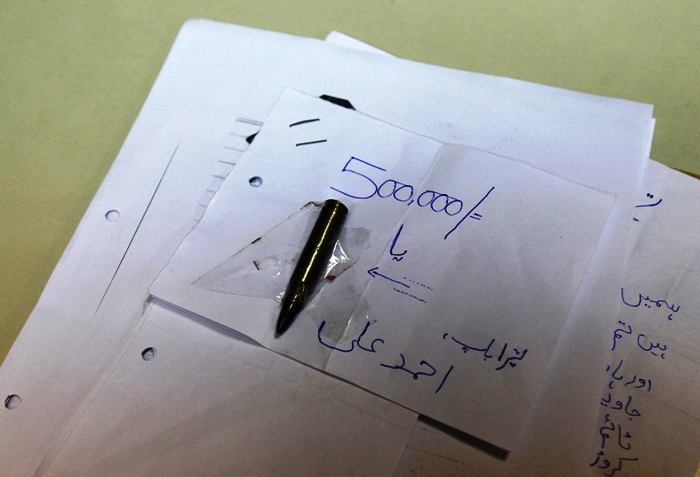

Extortion changes colour and spots from rural to urban, from one province to another. In urban centres of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, the victims of extortion are traders and landlords, not transporters. Similarly, extortion methods change from coercion to violent threats.

Dr Yousaf Sarwar, the chairman K-P Chamber of Commerce and Industry, admits that in June alone traders and industrialists in Hayatabad, Namakmandi, and other trade zones received threats from extortionists.

Meanwhile, in Peshawar, extortionists pose as militants when they make their calls. The July 21 blast in the city occurred outside the house of Waqar Orakzai, who had been threatened by extortionists and similar blasts have shaken K-P many times. Talking to The Express Tribune, Deputy Officer at Hayatabad check post Rahim Shah said it was difficult to seize extortionists posing as the Taliban. “Any complaint regarding a Taliban militant goes to the security agencies. We just take complaints and forward them. We do not have equipment to trace the calls made. If we do trace the calls, the SIMs are unregistered and extortionists flee to FATA, which is not in our jurisdiction.”

Balochistan’s a bubble?

Unlike K-P, police officials claim incidents of extortion in Quetta, Balochistan’s biggest urban area, are few. DIG Operations Fayyaz Sumbal said the police have been successful in nabbing extortionists. “In July, three cases were reported and solved,” he said.

However, truckers staged a protest in August last year, alleging that extortion was rampant and Frontier Corps personnel were involved. Balochistan Home and Tribal Affairs Secretary Akbar Hussain Durrani admitted that he had heard of unconfirmed incidents of FC personnel demanding protection money. “But the Home Department cannot verify these claims because they fall under the Interior Ministry.”

ISPR’s Lieutenant Colonel Fawad, who is based in Quetta, was tight-lipped about the allegations. “I cannot comment on individual cases, but I can assure you that if there have been such incidents, the culprits have been dealt with. Overall, I am absolutely certain that FC personnel have nothing to do with these allegations,” he claimed.

Blame-game and inside jobs?

Are the victims the perpetrators as well? If tribes, truckers, transporters and security officials are involved, who should be protected – and from whom? Along with the entanglement of the extortion network, the western half of Pakistan also suffers from the perplexity of possible inside jobs. But with officials and victims shrugging shoulders and pointing fingers, there seems no end to solving the national dilemma of extortion.

Published in The Express Tribune, August 29th, 2013.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

[poll id="1208"]

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

COMMENTS (2)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ

1722421515-0/BeFunky-collage-(19)1722421515-0-165x106.webp)

1732103737-0/Copy-of-Untitled-(55)1732103737-0-270x192.webp)

1726722687-0/Express-Tribune-Web-(9)1726722687-0-270x192.webp)

Extortion is a very serious crime, plain and simple. Where does the "dilemma" come from ?

In effect, the US is itself funding the opposition to the war it is fighting in Pakistan. Must be a world first where a country pays finances the enemy as well.