Short story: The odour of in-flight entertainment

Randhir reached for his bag and took out a book, 'Selected Stories of Saadat Hasan Manto'.

Randhir boarded the plane and thought, flying to Lahore is a refresher course in Pakistan.

He was pressed in at kissing distance, toxified by the cabin’s cocktail of biryani breath and anxious perspirations. His ears popped to medieval Arabic, infant cries, ringtones of lukewarm pop, the whispered sighs of an air hostess. He touched someone and did not need to say sorry. He stared into a soul and saw a sexagenarian foetus, dancing bhangra to the honks of small cars.

Among the passengers were old men in pyjamas and sweaters. Chubby families with bulging hand-luggage, thin on conversation. Ageing women with a fragrance you could bottle and brand ‘the wardrobe of melancholy’. Earnest MBAs, long since closed off to the mess beyond their noses, dreaming of a quiet air-conditioned patch. Over-groomed young women who glide above them all on the magic carpet of birthright. And so many young men, watching and internalising without articulation.

And this time there was Randhir, returning to the country he neither loved nor hated nor prayed for. It was enough to live there.

Randhir walked to his aisle seat in the middle row but found it filled by a woman. She wore a burqa, which did not concern Randhir. What did concern him was the man sat next to her whose eyes beamed out with menace like a car’s headlights in the dark.

“I think this is my seat,” Randhir said to the woman.

“Sir here, young man,” said the man, nodding at the empty seat on his other side.

“Sorry, uncle, but I asked for an aisle seat.”

“Sorry, son, but she is a woman.”

A silent stand-off ensued while the pre-flight chaos raged around them. The flight attendants were too busy. The nearby passengers watched but pretended not to. The diplomats were in first class.

After a while Randhir told the man, “Look, I can have the aisle seat and she can sit next to me and you can budge up,” but his failing words trailed off in their impotence. Somehow it was impossible to use other words like I am a man like you. I mean no more harm to your woman than you do. You do not need to be a buffer between your woman and the world. Not today, not here. I need the aisle seat because I have air sickness and need a quick exit route. The only threat I pose to your woman is projectile vomiting and with your actions you only increase this threat.

Randhir took a lap of defeat and entered the row from the other side. He nudged past the man in the far aisle seat, who had thoroughly enjoyed the scene, and tucked in next to the man with the beaming eyes.

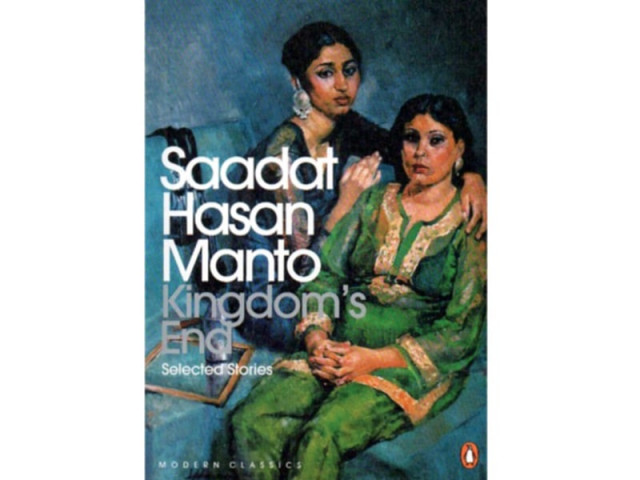

Just before chai was served Randhir reached for his bag and took out a book. It was the Penguin Modern Classics edition of the Selected Stories of Saadat Hasan Manto. He read for a while and sensed the man scanning the book over his shoulder.

It seemed the man was looking at the front cover rather than the words so Randhir angled the book to provide a better view. It had a painting by Iqbal Hussain of two prostitutes whose beauty and melancholy enhanced each other. The man was now staring. His wife was snoring through her burqa.

Randhir put down the book. “Sir, are you looking at something?”

The man’s nose crinkled. “Yes, that woman,” he said. “On the left.”

Randhir looked at the cover and then at the man. He searched the man’s face and found nothing. “Do you like her?”

“I think I know her,” said the man

“This is a painting on the cover of a book!”

“It was a long time ago, after the monsoons had come, and the rain would fall on the leaves of the peepal tree outside my window.”

Randhir looked at the woman in the painting. “What happened to her?”

The man breathed deeply. “What do you think?”

“She became your wife?”

At this the man looked at Randhir with the same expression as the woman in the painting, his eyes like two pots of dark ink which had run dry.

Landing at dawn, the plane’s doors flung open to a stairway to asphalt and Randhir breathed in the odour of Pakistan. In one whiff you could trace whatever you were looking for.

He was back on the soil of the country he neither loved nor hated nor prayed for. It was enough to live there.

Published in The Express Tribune, May 11th, 2012.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ