Domiciles: Don’t forget your place

Do we still need permanent residence certificates?

Affirmative action can be a double-edged sword. In Sindh, it comes in the form of domicile, which was introduced to protect people who lived in Sindh’s countryside. Today it works against them and the people who live in the cities.

Take the example of a boy in Karachi who has just sat his intermediate exams and wants to go to medical school. He passes the entrance test but doesn’t have enough marks to make the merit list. If he doesn’t qualify for an urban quota seat he will have to apply to another college in rural Sindh.

Then take the example of a young woman from Karachi who wants to get a job as a lecturer in a Sindh government college. But the job is only available for a rural quota, that is, someone from Larkana.

As with most affirmative action policies, domicile too started with the best of intentions, in 1951. It became a way to register citizens because there was no way to verify who had opted to stay in Pakistan in the years after Partition. After people registered as citizens, they could then qualify for government jobs or public schools and colleges.

“The domicile form was introduced to give proper representation to the people of Sindh,” explains Syed Nur Ahmed Shah, who served as deputy commissioner Tharparkar. “People from all over Pakistan come to settle in Karachi.” As the standard of education in Sindh is not very good, better qualified people from outside were attracted by the jobs. The domicile was meant to protect people from rural Sindh by ensuring they were given preference.

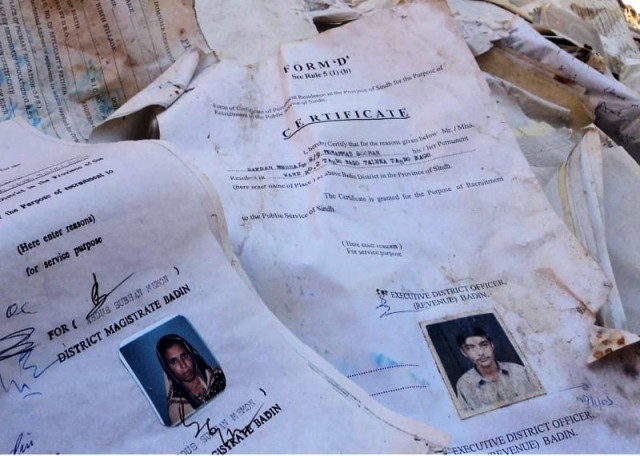

These documents were valuable because they established the origin, ethnic identity and status of migration of citizens. Application forms contain details of the district and province where citizens were born, when they arrived into the district they want a domicile of, and if they migrated from Bangladesh (former East Pakistan) or any other district, they must ‘surrender’ their original domicile certificate.

Migrants from India who arrived in Pakistan before April14, 1951 must submit a residence certificate. Questions in the permanent residence certificate form also seek to verify if and when the applicant’s parents resided in Sindh. This information is then used to determine if applicants qualify for a rural or urban quota.

Currently, urban Sindh is defined as the city and cantonment areas of Karachi, Hyderabad and Sukkur. The rest of the province is referred to as rural.

Requirements for a domicile form

1. Three passport-sized photos

2. Birth certificate from a grade 17 or above government officer/senator/MPA/MNA/member of a municipal committee or district council of the district

3. For applicants who migrated to Pakistan from India before April 14, 1951, a residential certificate from a government officer (see above).

4. For migrants from the former East Pakistan or any other district, the original domicile certificate must be surrendered

5. Documents of any immoveable property in the district

6. Documentary proof of occupation

7. Attested copy of an NIC or a Form ‘B’ for applicants below the age of 18

8. Attested copy of educational certificates to the current year

9. If aged less than 21, a photocopy of the NIC and domicile of the father/mother/guardian

10. Attested service certificate if in government employ

11. House documents: Utility bills, or an attested copy of the rent agreement if living in a rented house

12. For married men/women, photocopies of the spouse’s NIC, domicile and attested copies of their children’s birth certificates or Form ‘B’

13. Two attested photocopies of the NICs of residents from the neighbourhood

14. All photocopies, neighbour forms and residence certificates must be attested by a nazim, naib nazim or a class one officer

15. Rs200 fees to be paid at any branch of the National Bank of Pakistan

16. Affix a Rs1 ticket to all documents

17. Attestation of the domicile application by an Oath Commissioner

18. Attach original documents with photocopies

History of quotas

Kunwar Idris explains that the notion of reserved seats in government services and educational institutions came from Muslims living in pre-partition India, as leaders in Punjab demanded representation for the community because they had been kept ‘backward’. “Whether communal or provincial, the founding principle came from the Muslims.”

In the years after migration, there were Mohajirs coming into Sindh in large numbers. The basis of the domicile was that the rights of Sindhis were to be protected because of people from other provinces coming to Karachi and Sindh for search of jobs. The Mohajirs, up to this point, were dominant in the bureaucracy and education, while the indigenous Sindhis did not have the same influence. These quotas did not extend to other provinces such as Punjab – which also saw intense migration – because the migrants were all people who spoke one language. Rural Punjab, Idris says, had already benefited from the reserved seats it had won pre-Partition.

Required for admissions

Domicile forms are required at all public educational institutions in Sindh. The Dow University of Health Sciences asks for 17 documents with applications to its undergraduate programmes, including the applicant’s domicile, permanent residence certificate and NIC as well as the domicile and NIC of the applicant’s father. The University of Sindh requires: “Domicile certificate of candidate (or of father/ mother if the applicant is under 18 years of age and his/her name is included in it) and PRC (Original) to be shown at the time of payment in case of admission to quota oriented courses of study.”

History of the domicile form

The domicile form was introduced after the prime ministers of India and Pakistan, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Liaquat Ali Khan, signed the Liaquat-Nehru pact in 1950. It promised to protect minorities and improve relationships between the majority and minorities in their countries. It paved the way for the essential process of verifying who was a citizen of India and Pakistan, because there was intense cross-border migration in the years that followed Partition. After the Liaquat-Nehru pact was signed, Pakistan began to seal borders and in 1951, it introduced the Citizenship Act that required citizens to ‘claim’ and verify their citizenship by obtaining a domicile.

Illegitimate or insensitive?

The permanent residence certificate form used today has alarmingly insensitive language. At one point it asks the applicant if they were claiming the certificate of permanent residence because: he was born in Sind of illegitimate birth, and his mother, at the time of his birth, was domiciled in Sindh.” Some parts assume the applicant would be willing to answer this: “In the case of a person of illegitimate birth, the information required to be given above the father shall be given about his mother.” The form does not account for the female sex as all questions refer to applicants as “his” or “he”.

When the domicile was first introduced, it was an easy process to get it made. “Anyone could get a domicile, but there were more stringent requirements for the [certificate],” recalls former Sindh chief secretary Kunwar Idris. “You had to show details of property etc.”

Ex-Sindh chief secretary Syed Sardar Ahmed recalls how it worked in the post-Partition years. “You would go to the nearby mukhtiar kaar (assistant collector); he would ask you a few questions about when you had migrated and where you lived and issue it.”

The problem later arose on deciding how long a person had to live in an area before he could claim residence. Eventually, it was decided that a person who lived in an area for three years could get a PRC.

“Most people then wanted ‘rural’ domiciles because there were more jobs or would get ‘urban’ domiciles so they could keep jobs here,” Ahmed says.

Syed Nur Ahmed Shah says the forms were not as effective. He recalls that people would often produce false statements about how long they had resided in Sindh for and where they had obtained an education from. “While the form was effective for some, it has not helped to its desired extent.”

Muttahida Qaumi Movement leader Faisal Subzwari says it takes a few thousand rupees to produce falsified certificates. While he says the forms create resentment, it is a sensitive subject for his party since “we have to ensure that there are no further divisions”.

Any amendments to the Sindh Permanent Residence Certificate Rules of 1971 would be up to the government, since this is not a legislative act but administrative.

Ahmed and Shah agree that the forms are antiquated and not needed when citizens are required to get NICs and birth certificates. “These forms are just used to grab seats and jobs or for the Benazir Card, they need a domicile of a certain area,” Ahmed says.

Kunwar Idris, on the other hand, says that the quotas “did help Sindhis” and “one should not begrudge them that.” While he agrees that the corrupt and unfair practices in place and the way society is managed means that every job depends on “your connection”, the PRC and domicile should not be rejected on the grounds that it is “not being fairly implemented”.

One suggestion, floated by Ahmed, is that instead of getting a domicile and PRC made, applicants could just submit a birth certificate and NIC. Idris says referring all applications back to NADRA doesn’t make sense because it has nothing to do with the NIC, per se, but with the quotas.

Published in The Express Tribune, April 26th, 2012.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ