Stem cell treatment bears fruit

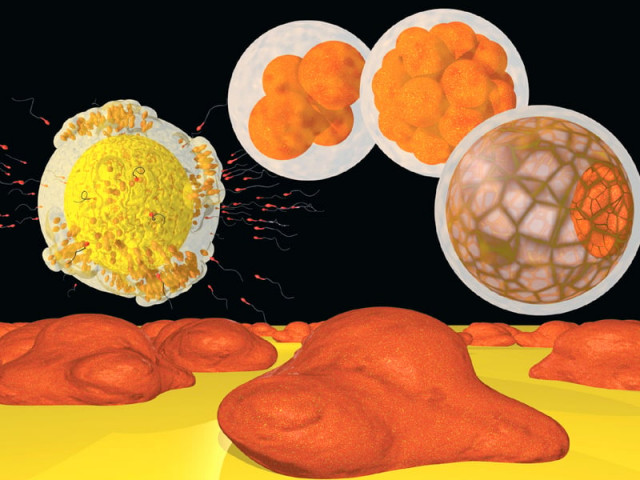

Stem cells are master cells that can differentiate into any of the 200 kinds of cells in the human body.

Before treatment, the 51-year-old graphic artist was legally blind, unable to read a single letter on a standard eye chart. She has suffered from Stargardt’s disease, the most common form of macular degeneration in young patients, since she was a teenager, and it was getting progressively worse.

A second patient, aged 78, suffered from dry macular degeneration — the leading cause of blindness in the elderly — and could not even see well enough to go shopping.

But after being treated with stem cells from a donated human embryo, both women have improved dramatically, researchers revealed.

Stem cells are master cells that can differentiate into any of the 200 kinds of cells in the human body. Their results are the first-ever report of the medical use of stem cells taken from human embryos, making them crucial barometers of whether the controversial technique will ever find widespread therapeutic uses.

In a paper published online in The Lancet on Monday, physicians at the University of California, Los Angeles, and scientists at biotechnology company Advanced Cell Technology report that the first two patients in the clinical trial suffered no adverse health effects from the treatment and seem to have benefited from it.

A week after having cells derived from a days-old embryo injected into her eye, the graphic artist could count fingers, and after one month she could read the top five letters on the eye chart. She can see more color and contrast, has started using her computer, and for the first time in years can read her watch and thread a needle. The macular degeneration patient recently went to the mall for the first time in years.

Objections and risks

Using human embryonic stem cells for research or treatment has incited controversy for ethical and medical reasons. Some opponents argue that because removing stem cells from days-old human embryos almost always destroys the embryo, the technique amounts to murder.

ACT is the only company currently testing human embryonic stem cells in study patients. Last November, stem-cell pioneer Geron announced that it was halting what had been the first-ever clinical trial of the cells-testing them in patients with spinal cord injuries-and leaving the field.

When Robert Lanza, chief scientific officer of ACT, approached ophthalmic surgeon Steven Schwartz of UCLA about leading the clinical trial, Schwartz asked for ethical advice from two of his patients: elderly nuns. They gave him the go-ahead, he said last year.

Even scientists who support stem cell research argue that they could be dangerous to use therapeutically. The very property that makes them so valuable in research — stem cells can morph into any of the kinds of cells in the human body — also makes them risky. They can form teratomas, a type of tumor that arises when stem cells differentiate into a profusion of cell types. reuters

Published in The Express Tribune, January 28th, 2012.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ