Full on

The protagonist Aruna is a loose cannon who seems to be capable of anything and is totally untrustworthy; for this reason she carries with her a sense of total freedom, where anything is possible, and therefore, exciting. The novel suffers from a fantastic beginning, with excellent pacing, and an astute portrait of a woman very much in distress. I say suffers because that sets the bar for a fantastic end even higher. The beauty of this book, however, is not so much in the plot that is of the surprise-twists-and-turns variety. It is in the delineation of the psychological states of the characters, in particular the protagonist Aruna and Hari Hassan, a bed-ridden, debilitated once-famous Bengali poet whose connection to Aruna is not immediately clear. We are introduced to him early on, knowing only that he is the author of a volume that she has been reading. It is one line from this volume that takes Aruna off the deep end, prompting her to simply walk out on her husband and her life whilst in the middle of breakfast. Priceless.

Hari Hassan lies in his hospital bed, waiting to die, and it is his delicious sense of humour that makes the horrific wreck of his body and situation bearable for the reader, “He had hopefully signed the Do Not Resuscitate form, hoping that his next choking fit would be enough to finish the job.” The novel is part black comedy, part existential nightmare. The author’s sense of comic timing is impeccable.

Ejaz or Jazz, is a childhood lover who is being tormented by the return of Aruna, “The moment passes, and Jazz is aware that he is just a ridiculous, half-naked figure, lying on the floor, obsessing about someone who is walking back into his life as thoughtlessly as she left it.” The deft hand of the novelist never allows her characters to wallow in self-pity for too long, rather she chooses often and mercilessly to point out the essential absurdity of existence.

Besides riding out the Aruna/Jazz connection, we travel the expanse of a friendship of some 40-odd years between Hari Hassan, a Bengali and one Pakistani, Anwar who, “was someone whose presence was more important than his absence. In his absence he left very little impression.” Hari Hassan lies debilitated in his hospital bed recalling his dear friend and the circumstances that brought them together, kept them together and also pried them apart, “They had briefly parted company during the civil war, when East Pakistan broke away from West Pakistan…and for the first time the friends were on opposing sides, idealogically and politically.” The politico-historical dimension of the novel is another layer, lightly cast over the story. At the core of the novel seems to be the exploration of the idea of the authentic self. “Yes, that’s it, exactly. I’m a fake. It’s like you know me already,” Aruna says in jest, but means every word. The poet Hari Hassan too, describes himself as such. The odyssey of Aruna is to discover if such a thing as the authentic self exists. Both she and the ailing poet suffer their own version of hell to reach the minotaur at the heart of the labyrinth, and slay him.

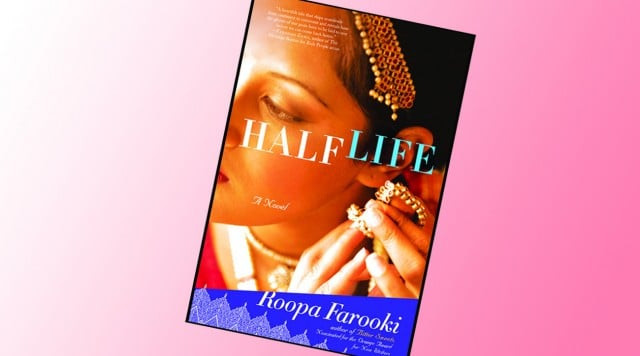

It is not the obvious plot “shockers”, that are the most compelling in Half Life. At times these plot devices seem to drown in messy explication. It is the subtler connections that are convincing and the manner in which the relationships between all the characters linked by the quote at the very beginning slowly unfurl, eventually to be tied back up into a neat bow for the dénouement.

Published in The Express Tribune, July 18th, 2010.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ