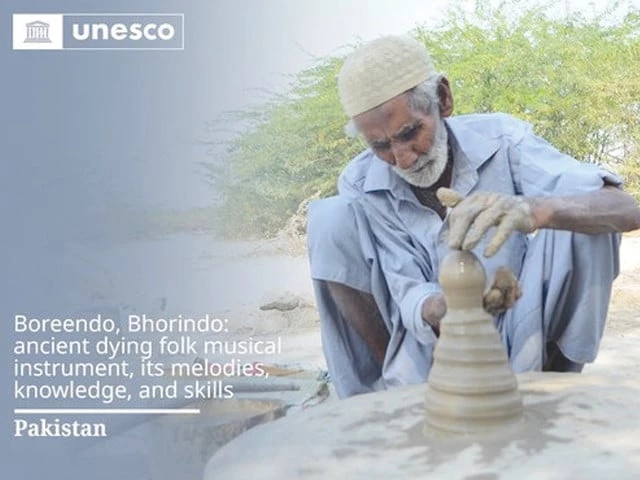

Clay instrument, timeless echo

Sindh rallies to save fading Boreendo after UNESCO listing

The Boreendo's re-emergence on the global cultural map this week offered more than a symbolic gesture toward an artefact of antiquity as it marked a long-overdue acknowledgement of a fragile craft that has carried the breath, memory, and mysticism of Sindh for 5,000 years, yet now stands on the edge of extinction.

Pakistan's ancient clay wind instrument was formally added to Unesco's Intangible Cultural Heritage list on Tuesday, underscoring the need for its urgent safeguarding, and giving fresh momentum to the struggle to keep its sound alive.

Fashioned from simple clay and shaped into a small hollow sphere punctured by sound holes, the Boreendo carries a voice that drifts between breath and invocation. Its design — often adorned with delicate hand-painted motifs by village women — reflects a tradition born of earth, simplicity, and sustainable craft.

Historians trace its lineage to the Indus Valley Civilisation, underscoring its status as the oldest surviving folk instrument of Sindh and a rare link to South Asia's earliest musical expressions.

For centuries, its soft, meditative tones have resonated through winter bonfires, Sufi gatherings, and rural festivities, embedding the instrument deep within Sindh's communal and spiritual rhythms. Cultural experts say the Boreendo's inscription confirms that even the most modest objects, shaped by hand and sustained through oral tradition, can carry vast civilisational memory.

But the tradition has dwindled to a precarious point. According to official, only one master musician, Ustaad Faqeer Zulfiqar, can still perform the instrument's full repertoire, while a single master potter, Allah Jurio, retains the knowledge required to craft it with precision.

Their survival as the final custodians of the craft speaks to a broader erosion. Younger generations have turned toward urban livelihoods, squeezing traditional arts into the margins. The result is a cultural inheritance slipping out of everyday life, its continuity reliant on two ageing experts whose skills have no clear heirs.

This sense of urgency underpinned Pakistan's nomination, which followed what the country's Embassy in France described as an intensive consultative process involving the Sindh government, Pakistan's Mission to Unesco, and Unesco Headquarters.

The effort drew momentum from Keti Mir Muhammad Loond village in Sindh, where the community itself initiated calls for preservation after witnessing the craft's rapid decline. Their work helped form the backbone of a four-year safeguarding plan for 2026 to 2029, designed to revive the Boreendo not as a museum curiosity but as a living cultural practice.

The plan proposes establishing a community music school, integrating Boreendo heritage into both formal and informal education, and expanding digital tools to reach younger learners whose cultural exposure increasingly occurs online.

Unesco adopted the decision during the 20th Session of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in New Delhi, giving the revival formal international backing.

In its announcement, Unesco described the instrument as a unique spherical creation known for its "haunting, soulful melodies played during winter bonfires and cultural festivals in Sindh." In a post on X, the organisation called the Boreendo an ancient dying folk instrument whose "melodies, knowledge, and skills" required urgent global support.

Pakistan's Permanent Delegate to Unesco, Ambassador Mumtaz Zahra Baloch, hailed the inscription as "a proud moment" and paid tribute to the communities that protected the tradition long before institutional recognition.

She described the Boreendo as an enduring emblem of the Indus Valley's cultural continuity and a living expression of Sindh's artistic and spiritual identity, adding that the listing strengthened Pakistan's commitment to ensuring the transmission of its craftsmanship and musical legacy to future generations.

Sindh Culture Minister Zulfiqar Shah echoed the sentiment, calling the inscription "a very proud moment" for the province and the country. Writing on X, he said the recognition marked a historic milestone for Sindh's folk music, artisans, and cultural identity. He offered particular thanks to Ustaad Faqeer Zulfiqar and master craftsman Ustaad Allah Dino, praising their resilience in preserving a tradition that could easily have vanished.

He also acknowledged the efforts of the Sindh government, the federal authorities, Unesco, and cultural expert Meeza Ubaid, whose combined work helped secure the long-sought listing. For many in Sindh, the decision feels like the first step in reclaiming a sound that has echoed across centuries - a modest clay sphere carrying the weight of an entire civilisation's artistic spirit.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ