A new AI cold war is emerging, and Pakistan must avoid becoming collateral damage

Proposals to restrict high-end chips to cloud rental could leave AI use dependent on US servers

Though the recently released US-China Economic and Security Review Commission report offers interesting insights into the love-hate dynamics of the US-China relationship, it also highlights concerns that could affect Pakistan in the long run.

The report acknowledges military cooperation between China and Pakistan and recognises the supremacy of Beijing's HQ-9 air defence system, PL-15 missiles and J-10 aircraft. However, the commission did not raise any concerns regarding China's offer to sell 40 J-35 fighter jets, KJ-500 aircraft and missiles to Pakistan in June 2025, showing that the US views Pakistan as a responsible stakeholder that is not fully aligned with either camp.

The report mentions that Pakistan imports surveillance technologies from China, including facial recognition systems, AI-driven monitoring platforms and digital ID systems, under China's Digital Silk Road strategy to support initiatives such as "safe cities." This should not raise an alarm, as Pakistan has legitimate security needs arising from two decades of terrorist threats.

Nevertheless, the fact that Pakistan is not explicitly discussed, unlike countries such as Russia and Iran, indicates that our strategy of maintaining strategic balance to extract benefits from both powers is working in our favour. However, what should concern Pakistan is the growing hostility between the two nations over cutting-edge AI technology and enabling computer chips.

The committee proposed that the US should shift from selling AI chips to renting them via cloud services when the performance capabilities of these chips exceed a given threshold. This means that, in future, developing countries like Pakistan won't be able to build independent GPU-powered data centres and would instead be forced to rely on servers in the US.

Access to such cloud-based AI compute would then be subject to use-case authorisation, with quotas varying by country. Even commercial entities outside the US would face FATF-style know-your-customer requirements to prevent AI computing from being used for military research or surveillance projects.

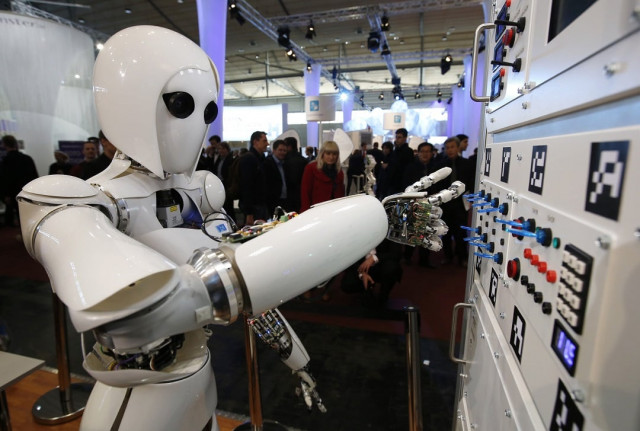

The committee also expressed concern over China's acquisition of German company Kuka, a leading manufacturer of robotic arms and automation solutions. This signals that advanced AI-powered robotics will become another battlefield in global technology competition.

The semiconductor trap

The commission's recommendation to shift high-end AI chips from sale to cloud-based rental reflects a fundamental shift in thinking: technology access is no longer about commerce but control. If implemented, it would create a two-tier world, countries capable of developing their own AI infrastructure and those perpetually dependent on foreign servers, with their data, algorithms and applications subject to US scrutiny.

The USCC report makes clear that technology competition between major powers will intensify, with export controls tightening, supply chains fragmenting and access to advanced technologies becoming increasingly conditional.

Pakistan may soon find itself forced to choose between dependence on China's technology ecosystem and reliance on Western, primarily American, technology. At the government level, Pakistan often procures Chinese solutions, yet our research institutions and universities remain heavily dependent on US-based chips for critical research and development.

Pakistan's National AI Policy and ongoing data centre investments could be rendered obsolete if this rental-only regime is implemented before the country secures essential hardware. Pakistan must recognise this threat early. We should immediately stockpile existing-generation AI chips, particularly Nvidia A100/H100-class GPUs and their equivalents, which are still available for purchase but may soon face export restrictions.

At the same time, we must invest in AI chip design capabilities using open architectures such as RISC-V, though not in manufacturing, which requires tens of billions of dollars. Pakistan should also negotiate technology-transfer agreements for semiconductor packaging and testing, and build relationships with emerging chip makers. We should also join regional technology cooperation consortia, such as the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organisation, of which Pakistan is a member.

The alternative is a future where Pakistan's AI ambitions require American permission, our manufacturing competitiveness depends on Chinese goodwill, and our economic development is constrained by technologies controlled by others. This is not merely an economic threat; it is an existential challenge to sovereignty in an era where technology is power.

The next two to three years represent a critical window. Technologies and capabilities available today may be restricted tomorrow. The USCC report is a roadmap of the technological fault lines that will define the 21st century. Pakistan cannot match the technology superpowers in resources or scale, but we can build a resilient and diversified technology ecosystem that maintains access to multiple sources. Our focus should be to avoid being caught on the wrong side of those fault lines while the window for action remains open. That window is closing faster than most realise.

The writer is a Cambridge graduate and is working as a strategy consultant

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ