Europe rethinks art security after Louvre heist

Experts point to Naples' forensic mapping as a model that could foil future robberies

Europe's leading museums have gone on high alert following the shocking theft of jewels from Paris's Louvre Museum, as attention turns to how one Italian collection may have cracked the code for safeguarding cultural treasures.

Inside the Tesoro di San Gennaro museum in Naples, a quiet revolution in art protection has been under way for over a decade. Here, a team of gemology experts has been meticulously creating a forensic map of its priceless artefacts — a method some say could have made it impossible for thieves to profit from the Louvre heist.

The team, led by investigative gemologist Ciro Paolillo, has spent more than ten years studying the museum's most valuable jewels, photographing over 10,000 stones under microscopes and specialised lighting. The result is a detailed "fingerprint" of each gem — a record so precise that experts compare it to human DNA.

According to Paolillo, this system of gem mapping could thwart attempts to resell stolen stones. "If the Louvre had adopted this security system, thieves would not be able to resell the stones from the stolen jewellery," he told Reuters. "The stones would be identified, even if cut, at the first official quality certification by an international body."

While European museums remain tight-lipped about their current security protocols, the Naples model offers rare insight into the behind-the-scenes battle to protect Europe's cultural wealth.

The Louvre, for its part, has yet to confirm whether similar forensic measures had been applied to the stolen pieces. Museum director Laurence des Cars earlier admitted she had repeatedly raised alarms over deteriorating security. She revealed that the centuries-old building's surveillance system failed to cover parts of the exterior, including the window the thieves reportedly used to break in.

French authorities have since arrested several suspects, though prosecutors have declined to release details, warning that leaks could jeopardise the search for both the perpetrators and the missing jewels.

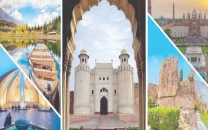

As Paris investigates, Naples has emerged as a case study in what rigorous prevention can achieve. The Tesoro di San Gennaro — a collection spanning seven centuries of devotion, art and history — is considered among Europe's most valuable religious treasuries. It includes gifts from popes, kings, and nobles, such as a diamond-and-emerald cross donated by Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon's elder brother and former King of Naples.

Nestled beside Naples Cathedral, the museum houses more than 21,000 artefacts, among them a bishop's mitre encrusted with nearly 4,000 precious stones and a necklace boasting 1,500 gems. Together, the two pieces alone are estimated to be worth around €100 million ($116 million).

The collection's silver busts — 53 in total, mostly from the 17th and 18th centuries — weigh about 200 kilograms each. These relics trace Naples's deep connection between faith, art and craftsmanship, and are owned not by the Vatican or the state, but by the people of Naples. The museum is managed by the Deputazione, a lay institution founded in 1527.

Paolillo's team has gone beyond gemstones. By analysing samples of silver and gold, they were able to trace many artefacts back to specific workshops in the city's historic Goldsmiths' Quarter. However, he admits that if modern thieves chose to melt down the masterpieces, the mapping would be useless. "The criminals would melt down the masterpieces, making it impossible to understand the alloy," he said.

The collection's survival story is remarkable in itself. In 1975, it narrowly escaped a robbery attempt organised by the local mafia, the Camorra. Following that incident, the treasures were stored in the vault of the Bank of Naples for nearly 30 years, before reopening to the public in 2003. Despite Naples's reputation for crime, no theft has occurred since.

That record, according to museum vice president Riccardo Carafa d'Andria, is due to both advanced security systems and the deep reverence locals hold for their patron saint, San Gennaro. "We have anti-theft security windows, all equipped with alarms. We have a military patrol on duty 24 hours a day," he said. "And if, unfortunately, any objects were to be stolen, the mapping of the stones would allow us to recognise them."

Carafa d'Andria added that devotion plays its own protective role. "Out of deep devotion to their patron saint, Neapolitans do not touch the Treasure of San Gennaro - and they would never allow anyone else to touch it either."

Across Europe, curators and directors are now re-evaluating their security frameworks as the Louvre theft exposes the vulnerabilities of even the world's most prestigious institutions. The theft has also reignited debate over the balance between accessibility and protection in museums that house humanity's shared heritage.

The Naples model shows that innovation and tradition can coexist — forensic science complementing centuries-old faith and craftsmanship. As investigators trace the stolen gems from Paris, one lesson seems clear: in a world where priceless art can vanish overnight, prevention remains the most precious treasure of all.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ